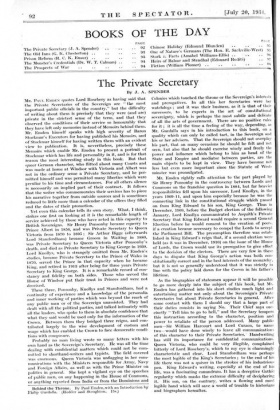

The Private Secretary

By J. A. SPENDER

Mn. PA1.71. EMDE.N. quotes Lord Rosebery as.having said that the Private Secretaries of the Sovereign are " the most important public officials in the country," but the difficulty of writing about them is precisely that they were (and are) private in the strictest sense of the term, and that they observed the conditions of their service so honourably that they have left only memories instead of Memoirs behind them. Mr. Emden himself speaks with high severity of Baron Stockmar's Executors for having published his Memoirs, and of Stockmar himself for having written them with an evident view to publication. It is, nevertheless, precisely these Memoirs which enable Mr. Emden to present a portrait of Stockmar which has life and personality in it, and is for that reason the most interesting study in this book. But that queer German character, who flitted about many Courts and . was made at home at Windsor with Victoria and Albert was not in the ordinary sense a Private Secretary, and he per- mitted himself and was permitted many liberties which were peculiar to his time and circumstances. For all others silence is necessarily an implied part of their contract. It follows that the writer who commemorates their services has to piece his narrative together from outside sources and is sometimes reduced to little more than a calendar of the offices they filled and the dates of their promotion.

Yet even this calendar tells its own story. What, I think, strikes one first, on looking, at it is the remarkable length of service achieved by those who have acted in this capacity to British Sovereigns. Sir Henry Ponsonby became equerry to Prince Albert in 1856, and was Private Secretary to Queen Victoria from 1870 to 1895 ; Sir Arthur Bigge (afterwards Lord Stamfordham) became Groom in Waiting in 1880, was Private Secretary to Queen Victoria after Ponsonby's death, and died as Private Secretary to King George in 1930. Lord Knollys, who is strangely omitted from Mr. Emden's studies, became Private Secretary to the Prince of Wales in 1870, served the Prince • in that capacity when he became King, and retired in 1913 after. being for three years Private Secretary to King George. It is a remarkable record of con- stancy and fidelity on both sides. Those who served the House of Windsor put their trust in Princes and were not deceived.

These three, Ponsonby, Knollys and Stamfordham, had a continuity of experience and a knowledge of the personalia and inner working of parties which was beyond the reach of any public man or of the Sovereign unassisted. They had ,dealt with all the political parties, and talked intimately with all the leaders, who spoke to them in absolute confidence that what they said would be used only for the information of the Crown. Between them they bridged three reigns, and con- tributed largely to the wise development of custom and usage which has enabled the Crown to face democratic condi- tions with composure.

Probably no man living wrote so many letters with his own hand as the Sovereign's Secretary. He was all the time dealing with confidential matters which could not be com- mitted to shorthand-writers and typists. The field covered . was enormous. Queen Victoria was unflagging in her com- munications with the Ministers responsible for Army, Navy and Foreign Affairs, as well as with the Prime Minister on politics in general. She kept a vigilant eye on the speeches of public men, on any happening in the House of Commons, or anything reported from India or from the Dominions and Behind the Throne. By Paul Emden,with an Introduction by Philip Guedalla. (Hodder and Stoughton. 15s.) Colonies which touched-the throne or the Sovereign's interests and prerogatives. In all this her Secretaries were her watchdogs ; and it was their business, as it is that of their successors, to be experts in the art of constitutional sovereignty, which is perhaps the most subtle and delicate of all the arts of government. There are no positive rules for it ; it is all the time a feeling of the way, depending, as Mr. Guedalla says in his introduction to this book, on a quality which can only be called tact, in the Sovereign and • his or her advisers. That the Sovereign should not overplay his part, that on many occasions he should be felt and not seen, but also that he should exercise wisely and freely the power and influence which belong to him as head of the State and Empire and mediator between parties, are the main objects to be kept in view. They have become not less but even more important since the Statute of West- minster was promulgated.

Mr. Emden rightly calls attention to the part played by Sir Henry Ponsonby in the controversy between Lords and Commons on the franchise question in 1884, but far heavier responsibilities fell upon his successor, Lord Knollys, in the years 1909-11, and upon him especially because he was the connecting link in the constitutional struggle which passed on from King Edward to his son, King George. Thus in December, 1909, before the Budget election of the following January, Lord Knollys communicated to Asquith's Private Secretary that King Edward would require a second General Election before he would consent to the creation of peers, if a creation became necessary to compel the Lords to accept the Parliament Bill. The presumption therefore was estab- lished in King Edward's reign that, if a second election were held (as it was in December, 1910) on the issue of the House of Lords, the Crown would use its prerogative to give effect to the decision of the electors. There are very few in these days to dispute that King George's action was both con- stitutionally correct and in the best interests of the monarchy, but it is not so generally understood that it was strictly in line with the policy laid down for the Crown in his father's lifetime.

As the biographies of statesmen appear it will be possible to go more deeply into the subject of this book, but Mr. Emden has gathered into his short studies much light and entertaining matter not only about the Sovereign's Private Secretaries but about Private Secretaries in general. After some contact with them I should say that a large part of their duties consists in saying No. Their Chief says suc- cinctly " Tell him to go to hell," and the Secretary tempers this instruction according to the character, position and power to retaliate of the person addressed. Many public men—Sir William Harcourt and Lord Curzon, to name two—would have done wisely to leave all conummications of this character to their Private Secretaries.' Handwriting has still its importance for confidential communications. Queen Victoria, who could be very illegible, complained bitterly of Lord Rosebery's, which to my eye is charmingly characteristic and clear. Lord Stamfordham was perhaps the most legible of the King's Secretaries ; to the end of his life there was not a quiver in the strokes of his industrious pen. King Edward's writing, especially at the end of his life, was a fascinating conundrum. It has a deceptive Gothic regularity which masks the extreme difficulty of deciphering it. His son, on the contrary, writes a flowing and most legible hand which will save a world of trouble to historians and biographers hereafter.

Previous page

Previous page