SCOTLAND

Boswell in the dog-house

William Cash

APRIL 1791 was one of the blackest months in James Boswell's life. He was still brooding over the death of his wife, his scheme to get Dr Johnson into Poets' Corner was meeting opposition and his friends suspected he was turning into a bore: bad enough for any journalist, barris- ter and aspiring politician but the kiss of death for one who was now aged 50, a moping alcoholic and up to his eyeballs in debt.

'Poor Boswell is very low and dispirited and almost melancholy mad — feels no spring, no pleasure in existence — and is so perceptibly altered for the worst that it is remarked everywhere.' (Courtenay to Malone)

Wednesday, 6 April: An excessive wet day. Did not stir out. Was low-spirited.

Boswell shut himself in his London study, anxiously hunched over the final proofs of his magnum opus. Three rival Johnson books — including the 'official' biography — had already beaten him to the book- shops and he had been warned that selling a bulky two volume edition at two guineas could be suicidal. He needed the money badly, to keep his sons at Eton and Westminster and to pay the mortgage on part of his ancestral estate in Scotland. Later he wrote to his friend Temple:

My life of Johnson is at last drawing to a close. 1 am correcting the last sheet and have only to write an advertisement . . . I am present in such bad spirits and have every fear concerning it — that I may get no profit, nay, may lose — that I may make enemies and even have quarrels.

Published on May 16 1791 Boswell's Life of Johnson was a bestseller. Yet it never solved his financial worries and made him enemies for having committed the crime of Printing men's unguarded letters and con- versation in a book. Contemporary reports said he became shunned by polite society and died five years later of a bladder swollen to the size of a balloon by drink.

Two hundred years old next month, the Life of Johnson is widely regarded as the greatest of all biographies. But ever since Boswell's frank private papers were found inside various croquet boxes in Malahide castle in the 1920s and sold to Yale, his reputation has been a prickly subject in literary circles, and much sniping has en- sued over whether the greatness of the Life really belongs to author or subject. Many scholars have distanced themselves from a man they see as a debauched and craven Watson trailing along at the heels of a superior Holmes.

I did not dine and was somewhat lowish. At night I strolled into the Park and took the first whore 1 met, whom I without many words copulated with free from danger, being safely sheathed. She was ugly and her breath smelt of spirits. 1 never asked her name. When it was done she slunk off. 1 had a low opinion of this gross practice and resolved to do it no more. (31 March 1763)

But he was tempted time and again, even when his wife lay ill in bed. As Dr Richard Luckett, the distinguished Pepys scholar explained: 'There is a terrible amount of jealousy over the Life. As an absolutely dreadful man Boswell is an embarrassment to serious Johnsonians who regard him as a pip-squeak. But Johnson was almost entirely created by Boswell and without his genius the famous doctor would have been very largely ignored.'

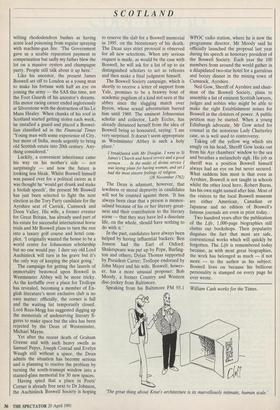

The present James Boswell, a vivacious 45-year-old former racing driver who lives in a converted kennel on the drive of his family estate in Ayrshire, has had enough. Disappointed at the wretched scale of his ancestor's 250th birthday celebrations last year, he is masterminding a truly Boswel- lian scheme, involving seeing his ancestor into Poets' Corner — of which more later — himself into the House of Commons and his Auchinleck estate turned into another Gleneagles which he hopes will restore his ancient Scottish name and fortune to its former 18th-century glory. (In 1790 Bos- well wrote to his heir: Remember always our ancient family, for that is the capital object).

Wearing a lemon Shetland jumper and rakish tassled loafers, Mr Boswell leads through to his elegant drawing-room, offers a whisky and cheerily explains how he has ended up living in the old family dog-house. He inherited the stately neo- classical mansion and estate aged 23, penniless and clobbered by death duties. Most of the family money had been lost on drink and gambling, the decent furniture vanished to Ireland. The house had an unfortunate war, with several hundred Free French and Poles using his Adames- que gargoyles and urns for bazooka prac- tice. A botanical expert has diagnosed his

SCOTLAND

wilting rhododendron bushes as having acute lead poisoning from regular spraying with machine-gun fire. 'The Government gave us a sizable reparation payment in compensation but sadly my father blew the lot on a massive oysters and champagne party. People still talk about it up here.'

Like his ancestor, the present James Boswell set off to London as a young man to make his fortune with half an eye on joining the army — the SAS this time, not the Foot Guards of his ancestor's dreams. His motor racing career ended ingloriously at Silverstone with the destruction of his Le Mans Healey. When chunks of his roof in Scotland started getting stolen each week, he installed a guard and placed a Boswel- lian classified ad in the Financial Times 'Young man with some experience of City, but more of India, needs urgently to bring old Scottish estate into 20th century. Any- thing considered.'

Luckily, a convenient inheritance came his way on his mother's side — not surprisingly — and now the future is looking less bleak. Whilst Boswell himself was passed over for a political career as it was thought he 'would get drunk and make a foolish speech', the present Mr Boswell has just been selected to fight the next election as the Tory Party candidate for the Ayrshire seat of Carrick, Cumnock and Doon Valley. His wife, a former eventer for Great Britain, has already used part of his estate for successful international horse trials and Mr Boswell plans to turn the rest into a luxury golf course and hotel com- plex. 'I originally wanted the house to be a world centre for Johnsonian scholarship but no one would pay. I dare say old Lord Auchinleck will turn in his grave but it's the only way of keeping the place going.'

The campaign for getting the laurels of immortality bestowed upon Boswell in Westminster Abbey will be more tricky. As the kerfuffle over a place for Trollope has revealed, becoming a member of En- glish literature's most exclusive club is no easy matter: officially, the corner is full and the waiting list temporarily closed. Lord Rees-Mogg has suggested digging up the memorials of undeserving literary fi- gures to make space but the idea has been rejected by the Dean of Westminster, Michael Mayne.

Yet after the recent death of Graham Greene and with such heavy swells as Samuel Pepys, Joseph Conrad and Evelyn Waugh still without a space, the Dean admits the situation has become serious and is planning to resolve the problem by turning the south-transept window into a stained-glass memorial for 30 new spaces.

Having spied that a place in Poets' Corner is already free next to Dr Johnson, the Auchinleck Boswell Society is hoping to reserve the slab for a Boswell memorial in 1995, on the bicentenary of his death. The Dean says strict protocol is observed for all new selections. When any serious request is made, as would be the case with Boswell, he will ask for a list of up to six distinguished scholars to act as referees and then make a final judgment himself.

The Boswell Society campaign, which is shortly to receive a letter of support from Yale, promises to be a brawny bout of academic pugilism of a kind not seen at the abbey since the slugging match over Byron, whose sexual adventurism barred him until 1969. The eminent Johnsonian scholar and collector, Lady Eccles, has already distanced herself from the idea of Boswell being so honoured, saying: am very surprised. It doesn't seem appropriate as Westminster Abbey is such a holy place.'

I breakfasted with Mr Douglas. I went to St James's Church and heard service and a good sermon . . . In the midst of divine service I was laying plans for having women, and yet I had the most sincere feelings of religion. (28 November 1762)

The Dean is adamant, however, that lewdness or moral depravity in candidates will not be counted against them. 'It has always been clear that a person is memor- ialised because of his or her literary great- ness and their contribution to the literary scene — that they may have led a dissolute life, on the whole, should have nothing to do with it.'

In the past, candidates have always been helped by having influential backers: Ben Jonson had the Earl of Oxford; Shakespeare was put up by Pope, Burling- ton and others; Dylan Thomas supported by President Carter; Trollope endorsed by John Major and his wife. Boswell, howev- er, has a more unusual proposer: Bob Moody, a former Country and Western disc-jockey from Baltimore.

Speaking from his Baltimore FM 93.1 WPOC radio station, where he is now the programme director, Mr Moody said he officially launched the proposal last year during his speech as honorary president of the Boswell Society. Each year the 100 members from around the world gather in a dilapidated two-star hotel for a garrulous and boozy dinner in the mining town of Cumnock, Ayrshire.

Neil Gow, Sheriff of Ayrshire and chair- man of the Boswell Society, plans to assemble a list of eminent Scottish lawyers, judges and nobles who might be able to make the right Establishment noises for Boswell in the cloisters of power. A public petition may be started. When a young Edinburgh advocate, Mr Gow acted for counsel in the notorious Lady Chatterley case, so is well used to controversy.

Taking off the yellow wig which sits snugly on his head, Sheriff Gow looks out from his Ayr chambers' window to the sea and breathes a melancholy sigh. His job as sheriff was a position Boswell himself always had an eye on but never secured. What saddens him most is that even in Ayrshire, Boswell is not taught in schools whilst the other local hero, Robert Burns, has his own night named after him. Most of the visitors to the local Boswell museum are either American, Canadian or Japanese and no edition of Boswell's famous journals are even in print today.

Two hundred years after the publication of the Life, 1,000-page biographies still clutter our bookshops. Their popularity disguises the fact that most are safe, conventional works which will quickly be forgotten. The Life is remembered today because, as with most great biographies, the work has belonged as much — if not more — to the author as his subject. Boswell lives on because his bellicose personality is stamped on every page he ever wrote.

William Cash works for the Times.

'The great thing about Knut's architecture is its marvellously intimate, human scale.'

Previous page

Previous page