Theatre

Lost world

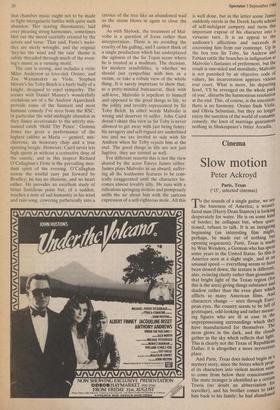

Christopher Edwards

Twelfth Night (Barbican)

John Caird's production of Twelfth Night is a delight. It is a triumph of stagecraft, of acting and direction; interestingly it is a triumph despite its own melancholy view of Shakespeare's comedy. Gone, probably for good, is the idea that the Comedies can be played as if they were regions of warmth and sunshine. The knowledge of Shakespeare's dramatic career as a whole seems to oblige the director to hold in view the tragedies and 'dark comedies' that lie ahead whose shadows must be seen to fall across the earlier work. In Stratford the harshness of this production seemed almost wilful, as if Caird had taken literally the acerbic view put out by Auden that 'Shakespeare was in no mood for comedy'. On its transfer down to London the bitter- ness and discomfort are there still, but they have been allowed to mellow. The mood of comedy prevails, albeit in a minor key.

Robin Don's set keeps boldly in step with Caird's interpretation. Orsino's and Olivia's palaces are perched on the rocky edge of a stormy Illyrian sea-board, fringed with ruined columns, and dominated centre-stage by the looming withered tentacles of a huge box tree. Viola enters pursued by storm, as the skies and seas behind her writhe in flashing yellows and greys, and Ilona Sekacz's apocalyptic strings and percussions erupt above. This talented composer's incidental music is always arresting, even if you take the view

that chamber music ought not to be made to fight intergalactic battles with quite such abandon. Her searing dissonances, laid over pleasing string harmonies, sometimes blot out the mood carefully created by the actors and verse. That said, Feste's melo- dies are nicely wrought, and the original 'hey-ho the wind and the rain' theme is subtly threaded through much of the even- ing's music as a running motif.

The cast is strong, and includes a virile Miles Anderson as love-sick Orsino, and Zoe Wanamaker as Viola. Stephen Moore's Sir Toby Belch is a burly bully of a knight, designed to repel sympathy. The scenes with Daniel Massey's wonderfully credulous sot of a Sir Andrew Aguecheek provide some of the funniest and most humane comedy I've seen from the RSC, in particular the wild midnight abandon as they dance accelerando to the utterly mis- named catch 'Hold Thy Peace'. Gemma Jones too gives a performance of the highest calibre as Maria — genteel, mis- chievous, an honorary chap and a true sporting beagle. However, Caird never lets high spirits in without a corrective dose of the caustic, and in this respect Richard O'Callaghan's Feste is the prevailing mor- dant spirit of the evening. O'Callaghan scorns the wistful zany put forward by Bradley: he has no illusions, and no heart either. He provides an excellent study of bitter fastidious poise but, of a sudden, touches a note of sad humanity in his wind and rain song, cowering pathetically into a

crevice of the tree like an abandoned waif as the storm blows in again to close the play.

As with Shylock, the treatment of Mal- volio is a question of focus rather than interpretation. There is no avoiding the cruelty of his gulling, and I cannot think of a single production which has underplayed the ugliness of the Sir Topas scene where he is treated as a madman. The decision, for modern sensibilities, is whether we should just sympathise with him as a victim, or take a robust view of the whole thing. It is surely important to show that, as a petty-minded bureaucrat, thick with self-love, Malvolio is repellent to himself and opposed to the good things in life, to the jollity and revelry represented by Sir Toby Belch. In other words Malvolio is wrong and deserves to suffer. John Caird doesn't share this view as Sir Toby is never allowed to get away with just being funny; his savagery and self-regard are underlined too and we are invited to side with Sir Andrew when Sir Toby rejects him at the end. The good things in life are not just fugitive, they are tainted as well.

For different reasons this is not the view shared by the actor Emrys James either. James plays Malvolio as an absurd, suffer- ing all the loathsome features to be com- ically exaggerated until the character be- comes almost lovably silly. He runs with a ridiculous springing motion and pompously sniffs the air about him with the cartoon expression of a self-righteous mole. All this

is well done, but in the letter scene James suddenly enrols in the Derek Jacobi school of self-indulgent campery and turns this important exposé of his character into a virtuoso turn. It is an appeal to the audience's affections and succeeds la cocooning him from our contempt. up la the box tree Sir Toby, Sir Andrew and Fabian rattle the branches in indignation at Malvolio's fantasies of preferment, but the result is one-sided and moralistic; Malvolio is not punished by an objective code of values, his incarceration appears vicious tout court. What is more, his departing howl, 'I'll be revenged on the whole pack of you', disturbs the harmonious resolution at the end. This, of course, is the intention; there is no harmony. Orsino finds Viola, and Olivia Sebastian, but they no longer enjoy the sanction of the world of romantic comedy; the knot of marriage guarantees nothing in, Shakespeare's bitter Arcadia.

Previous page

Previous page