At the end of the long reign in Spain

What kind of future under King Juan Carlos?

John Organ

General Franco, dying slowly in his rural Pardo Palace outside Madrid, refusing to give up power even though wracked by heart attacks every few days, was already discredited by the fact that Spaniards of all persuasions agreed that his last year was the most confused and unsuccessful of his reign.

Prince Juan Carlos of Bourbon, thirtyseven, will be proclaimed King of Spain, but it is still not clear what sort of Spain will emerge under his rule, or to what extent he will enjoy popular support. Many Spaniards believe that the speed at which Spain moves towards democracy will depend on the young King's first acts: on whether he announces free elections for a constituent assembly, on whether he grants an amnesty for political prisoners, and on whom he appoints as Prime Minister.

But it is just as likely that the young King, because of complications posed by the legislative machinery which General Franco has left him, will make no quick changes, and will play safe by retaining the cabinet of Carlos Arias Navarro for a couple of months. Franco's last illness has produced a sort of national paralysis in Spain, and, in the words of one opposition leader, "no one, from the extreme right to the Communists, wants to make a mistake."

Juan Carlos will be the first King of Spain since Alfonso XIII, his grandfather, went into exile in 1931 after discrediting the monarchy and allowing a period of military dictatorship. Since then Spaniards have lived through the heady days of the Second Republic, seen themselves so bitterly divided that the 1936-39 civil war was inevitable, and have lived deprived of political rights for nearly forty years under Franco — Juan Carlos bears some resemblances to Alfonso XIII, but he takes over a very different Spain from the poverty-stricken nation that his grandfather abandoned in 1931.

In the young King's favour is the real possibility of earning national gratitude, and thus the popular support that he needs, if he can quickly introduce authentic democracy while at the same time avoiding violent upheaval. Against him is the charge that he is a creation of the Franco regime, tarred by association with it, and by the oath that he took to uphold its principles when he was proclaimed King-designate in 1969.

This summer the Prince's father, Don Juan of Bourbon, heir of Alfonso XIII, once again disowned the arrangements under which General Franco installed the son as future king over the father's head. There has been talk in Madrid that Don Juan might act for his son as the sort of Prime Minister who stands above the fray and could bring both Conservatives and Communists together around the same table. But this seems wishful thinking. Don Juan, bluff, liberal, and a rather amateur foe of Franco, destroyed his own credibility many years ago by handing Juan Carlos over to Franco to be educated in Spain and groomed there for the throne. Nearly all' Spanish Monarchists, who include Conservatives, Liberals, Christian Democrats and Social Democrats, have come round to supporting Juan Carlos despite the family quarrel, and he also has the support of the Spanish armed forces and of the church. He does, however, need the blessing of his father both to establish his dynastic position and to enable him to rebut charges that he obtained the throne merely as a creature-of Franco. c.„The,. 1975 But who will be his first Prime Minister? pectat,or November 1,

There seems little doubt that, if he had a free choice, he would not retain Senor Arias, a well-intentioned but weak conservative who allowed Franco both to resume power after his 1974 illness and then to trample over cautious plans for liberalisation. Even less would his choice fall on figures of Franco's last-ditch bunker': Cabinet Ministers such as Jose Solis, or the President of the rubber-staMP Parliament called the Cortes, Alejandro Valcarcel. A more attractive candidate

is Jose Maria Areilza, the Count of Motrico, who paid two private visits to Juan Carlos during Franco's last agony. Areilza is articulate, polished, Franco's Ambassador in Washington and Paris until he went into semi-opposition several years ago to push the claims of Don Juan as political manager of the exiled Pretender, only to see his ambitions collapse when Juan Carlos was appointed to the throne in 1969. Areilza suffers from his image as a suave intriguer. A man of wealth lacking grass-roots political support, but he probablY has the skill to organise a coalition which would stretch from the moderate right even as far as the mainstream Socialist Party and other members of the hitherto illegal Opposition. , An even more attractive candidate would he Lieutenant-General Manuel Diez Alegria, one of the most respected officers in the Spanish Army, who lost his post as Chief of the Defence Staff last year for being too liberal in his politics. There are strong arguments for appointing a liberal military man as Prime Minister, but candidates of this sort are few, and the only others, ' with more dubious democratic credentials, are Admiral Pita da Veiga and the up-and-coming General Manuel Gutierrez Mellado.

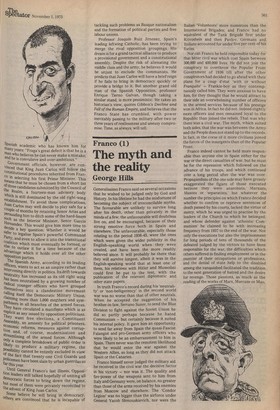

One man trumpeting his claims to be Prime Minister is Manuel Fraga Iribarne, once a bulldozing Information Minister in the Franco Cabinet who, to his credit, succeeded in abolishing press censorship, albeit at the price of retaining irksome restrictions on the media. Fraga is due to relinquish his post as Spanish Ambasador in London in mid-November. But his bid for power is vitiated by the fact that so many people share the opinion of one respected Spanish academic who has known him for many years: "Fraga's great defect is that he is a Man who believes he can never make a mistake, and he is convulsive and over-ambitious."

Government officials, however, are convinced that King Juan Carlos will follow the constitutional procedures inherited from Franco in selecting his first Prime Minister. This Means that he must be chosen from a short list of three candidates submitted by the Council of the Realm, a fourteen-man advisory body Which is still dominated by the old right-wing establishment. To avoid these complications, Juan Carlos may well decide to play safe for a Couple of months by retaining Senor Arias and Persuading him to ditch some of the hard-liners such as the Interior Minister, Senor Garcia Hernandez. This would give him more time to decide a key question: Whether it would be safer to legalise Spain's powerful Communist party, and even to allow it into the transitional coalition which must eventually be formed, or else to outlaw it for a time because of the advantage which it holds over all the other oPposition parties. The Spanish Army, according to its leading Officers, wants to act as an umpire rather than intervening directly in politics. Its_drift towards neutrality has increased as its old right wing • has been neutralised by a growing number of radical younger officers who have grouped themselves into a clandestine movement calling itself the Democratic Military Union, claiming more than 1,000 mettbers and sympathisers in all branches of the armed forces. They have circulated a manife,sto which is as explicit as any issued by opposition politicians. They want free elections, a Constituent Assembly, an amnesty for political prisoners, economic reforms, measures against corrup tion and, of course, modernisation and streamlining of the armed forces. Although Only a complete breakdown of public order is likely to produce a military regime, the

Possibility cannot be entirely excluded in view of the fact that twenty-one Civil Guards and Policemen have been slain by urban guerrilas so far this year. Until General Franco's last illness, Opposition leaders still talked hopefully of uniting all

democratic forces to bring down the regime,

but most of them were privately reconciled to the advent of King Juan Carlos. Some believe he will bring in democracy, Others are convinced that he is incapable of tackling such problems as Basque nationalism and the formation of political parties and free labour unions.

Professor Joaquin Ruiz Jimenez, Spain's leading leftwing Catholic, has been trying to merge the rival opposition groupings. His dream is for a grand tactical alliance to produce a provisional government and a constitutional assembly. Despite the risk of alienating the middle class and the army, he believes it would be unjust to exclude the communists. He predicts that Juan Carlos will have a brief reign if he 'fails to bring in democracy quickly or provide a bridge to it. But another grand old man of the Spanish Opposition, professor Enrique Tierno Galvan, though taking a similar stand, is more pessimistic. He takes an historian's view, quotes Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, and believes that the Franco State has crumbled, with power inevitably passing to the military after two or three years of restlessness and uneasy compromise. Time, as always, will tell.

Previous page

Previous page