SALAD DAYS IN BANGALORE

Gandhi prescribed Nature Cure for the

poor, Dhiren Bhagat takes it

with the rich

GANDHI did not care much for doctors. `Sometimes I think that quacks are better than doctors,' he wrote in his book Hind Swaraj, going on to observe: 'Hospitals are institutions for propagating vice.' His argu- ment was simple: The business of a doctor is to take care of the body, or, properly speaking, not even that. Their businesses is really to rid the body of diseases that may afflict it. How do these diseases arise? Surely by our negligence or indulgence. I overeat, I have indigestion, I go to a doctor, he gives me medicine, I am cured. I overeat again, I take his pills again . . . . The doctor intervened and helped me to indulge myself . . . . Men take less care of their bodies and immorality increases.' And that wasn't all. 'It is worth consider- ing why we take up the profession of medicine. It is certainly not for the purpose of serving huthanity. We become doctors so that we may obtain honours and riches . . . . Doctors make a show of their knowledge, and charge exorbitant fees. Their preparations, which are intrinsically worth a few pence, cost shillings. The populace, in its credulity and in the hope of ridding itself of some disease, allows itself to be cheated. Are not quacks then, whom we know, better than the doctors who put on an air of humaneness?'

I must admit the 'whom we know' is a bit disturbing, but of the many unusual things this unusual man said in the course of his long life this has always struck me as being particularly sound. For the past two weeks my mind has been returning to these words as I push and stretch, fast and sweat at the Institute of Naturopathy and Yogic Scien- ces, India's smartest nature cure establish- ment, and perhaps even its best known.

Gandhi would have approved of what they are doing to me. On my second day here they put me on a fast (two glasses of lime juice, two glasses of coconut water, unlimited quantities of filtered water) backed up by neem water enemas. On the fifth day I was on fruit juice, on the sixth on fruit, and it's been salads and sprouts ever since. But there is more to it than diet control. I wake at five and after a long walk in the farm and a game of badminton begin the yogic kriyas to cleanse my insides: three cups of lukewarm saline solution in one nostril and out of the other to sort out the nasal passage, six very large tumblers of a like solution drunk in between bouts of exercise in the gymnasium in order to effect a lavage of the entire alimentary tract and much else besides. (I drew the line one morning when the instructor inserted a thick wet waxed string deep into one of my nostrils and then urged me to use my middle and index fingers to pull it out of my mouth.) Then there are the treatments. Apart from the routine twice- daily mud packs on the eyes and abdomen I've had hip baths, chest packs, jet spray massages, underwater massages, mud baths, sun baths, oil massages, whirlpool baths, steam baths, arm and foot baths, saunas and even a plantain leaf pack where they tie you up in banana leaves and blankets and leave you in the hot sun to sweat it out. To keep you occupied the rest of the day there's yoga, meditation, table tennis and even a session of Jane Fonda's workouts on video just before supper. I skip that last diversion, and go for a walk on the farm instead, a bit like the 'Liar' Donne addressed in his epigram:

Thou in the fields walkst out thy supping hours, And yet thou swear'st thou has supp'd like a king: Like Nebuchadnezzar perchance with grass and flowers, A salad worse than Spanish dieting.

Salads have not always been considered good for one's health. In our times they were revived in America. Just two years before Sylvester Graham began his cam- paign for fresh fruit and vegetables, the New York Mirror argued (28 August 1830) that 'fresh fruit should be religiously for- bidden to all classes and especially chil- dren' and later, in 1832, with cholera afflicting the American cities and fruit and vegetables banned in Washington and New York, the Mirror reiterated common wis- dom: 'Salads are to be particularly feared.' Graham began his work in New York that very year using the Bible Christians (who lived on fresh vegetables) as an example to further his case against the ruling supersti- tion. He had a spectacular success and within three years the establishment had been won over: in its issue of 21 October 1835 the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal endorsed his case. In the Hydro- pathic Encyclopaedia (1851) Graham's assistant Dr Trail declared all fresh fruit and vegetables to be antiscorbutic and salads have been good news ever since.

External water treatment is the other part of naturopathy. Doubtldss some such cures were known to every sort of ancient people from the Chinese to the Aztecs, but in our times it was a peasant in Austrian Silesia who discovered them. In 1816 Vin- cent Priessnitz crushed his finger and then, 'as it were by instinct, plunged this injured member into water till it ceased bleeding'. Three years later a laden wagon broke the ribs of his left side and he treated himself with water again. This led him to a lot of experimenting and then finally he opened a clinic in Graefenburg where, by all accounts, he did rather well for himself. In the Handbook of Hydrotherapy (1844) Joel Shew quotes a Captain Claridge as saying that in 1841 there were under Priessnitz's care, 'an archduchess, ten princes and princesses, at least one hundred countesses and barons, military men of all grades, several medical men, professors, advocates &c — in all about five hundred.'

Naturopathy came to India exactly 100 years ago when in 1885 a Registrar in the Revenue Department in Andhra, one D. V. Sharma, came across Louis Kuhne's newly published The New Science of Heal- ing. He first used the book to cure his wife and then proceeded to translate the book into Telugu. Soon after, the Munsif Magis- trate of Benares, Krishna Swaroop, trans- lated the book into Hindi, and to this day it has been in these two states, U.P. and Andhra Pradesh, that naturopathy has been best received.

Gandhi came to naturopathy late. While in London in the late 1880s he had greedily read Henry Salt's Plea for Vegetarianism and started a short-lived vegetarian club in Bayswater, with Edwin Arnold as vice- president and himself as secretary, but he had remained unaware of the naturopaths.

It was in Johannesburg in 1901 that a German friend who ran a vegetarian res-

taurant lent him Just's Return to Nature, which prompted him to begin a series of experiments that would go on till the end of his life.

It was largely Gandhi's espousal of Nature Cure that made it so popular with

Congressmen. It was of a piece with khadi,

the homespun cloth Gandhi made a symbol of village self-sufficiency and the independ- ence movement. The Congress Party (which was also established in 1885, see 'Death of the Opposition', 26 January) met annually in the last week of every year; alongside it the All India Nature Cure Federation organised its annual do. 'My father, my uncle, they all came to Congress and naturopathy together, in 1919, when Gandhiji gave the call,' Dr Loorthy at the institute recalls. 'Nature Cure in those days moved hand in hand with Congress.'

Several brahmins in Congress took to naturopathy, largely, one suspects, be- cause their vegetarian diet prepared them for its discipline, but Nehru didn't think much of it. (He was a Kashmiri brahmin, the only brahmins who eat meat.) Conse- quently after Independence there was hardly any emphasis on naturopathy, it was allowed to gasp away in little ashrams chiefly in U.P. and Andhra. Morarji De- mi, whose naturopathy embraces auto- urine therapy, a discipline he learnt from

Armstrong's Water of Life (1948), who in turn derived it from the biblical command

'Drink waters out of thine own cistern' (Proverbs v 15), though Prime Minister for two years did nothing at all for naturopathy

except a short book Nature Cure (1978),

which he wrote while in prison during the Emergency. Hardly any money has been allocated to the naturopaths for research and, more important, government em- ployees are not reimbursed for the cost of naturopathic treatment. Because there isn't much money in naturopathy the brigh- ter medical students opt for allopathy. 'The real problem today,' Dr Moorthy mourn- fully says to me, 'is this: students who can't get into ordinary medical colleges come to the two naturopathic colleges; because of that it is very difficult to get good doctors. So even if we wanted to start another Institute, even if there were funds, where Would we get the doctors from?' He should know: his last job was as vice-principal of the Hyderabad college.

When in 1978 an industrialist who manu- factures aluminium products decided he was going to build and support a natur- opathic institute, he got in touch with Dr Moorthy who has ever since been the Chief Medical Officer here. It's a well-run place, clean, `spankingly modern', as an Amer- ican journalist recently described it, but hardly an ashram, which is what the brochure makes it out to be. A fifth of the Patients at any time are there free, a noble Provision, but the rest get the accommoda- tion they pay for: there are nests, huts, cottages and single and double rooms. Industrialists, I observed, made for the luxuriously furnished twin bedroom' nests, mere businessmen for the huts, Professionals for the cottages and the rest of the middle class contented itself with the single and double rooms. This is possibly a wise move: by offering different levels of comfort one attracts the widest possible spectrum of patients; nevertheless, the strong presence of the uncultured rich with their jiggling folds of fat — has made me distinctly uncomfortable. (Rajiv's 'bold, innovative' budget which scrapped death duties and brought income tax levels down is ritually praised whenever three people get together.) Otherwise, I feel excellent. I've lost four kilograms and I haven't felt fitter in years, but Gandhi's concern for the health of the villagers disturbs me as I guzzle my mango juice and hear three rich children tell each other all they've heard their parents say about champagne.

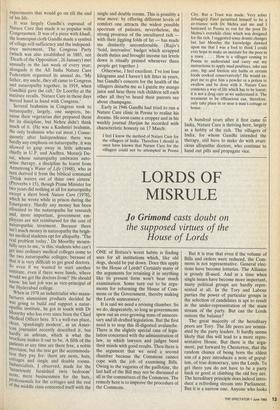

Early in 1946 Gandhi had tried to run a Nature Cure clinic in Poona to realise his dreams. He soon came a cropper and in his weekly journal Harijan he recorded with characteristic honesty on 17 March:

I feel I know the method of Nature Cure for the villagers of India. Therefore I should at once have known that Nature Cure for the villagers could not be attempted in Poona City. But a Trust was made. Very sober Jehangirji Patel permitted himself to be a co-trustee with Dr Mehta and me and I hastened to Poona to run for the poor Dr Mehta's erstwhile clinic which was designed for the rich. I suggested some drastic changes but last Monday the knowledge dawned upon me that I was a fool to think I could ever hope to make an institute for the poor in a town . . . . How is a villager coming to Poona to understand and carry out my instructions to apply mud poultices, take sun cure, hip and friction sitz baths or certain foods cooked conservatively? He would ex- pect me to give him a powder or a potion to swallow and be done with it. Nature Cure connotes a way of life which has to be learnt; it is not a drug cure as we understand it. The treatment to be efficacious can, therefore, only take place in or near a man's cottage or house. . . .

A hundred years after it first came to India, Nature Cure is thriving here, largely as a hobby of the rich. The villagers of India, for whom Gandhi intended the therapy, still have to make do with avari- cious allopathic doctors, who continue to hand out pills and propagate vice.

Previous page

Previous page