ARTS

Journey to the world's end

Marc Stengel on an exhibition which shows the conquering spirit of the Viking Age There are loot and booty and spoils of war. There are feats of derring-do, tribula- tions of adventure, exultations of conquest and discovery. There is also, in a far corner of the 6,000 sq ft devoted to the exhibition entitled The Vikings — The North Atlantic Saga, a tiny cloak — a hooded, split-front tunic — measuring a scant 60cms high. It is a rich russet brown, homespun, remarkably intact considering its six or seven centuries' hibernation at 'the world's end', as mediae- val Greenland was known.

To look into the deep shadow that fills the upraised hood of this tiny garment of a child is to peer directly into a mystery unparalleled in human experience. For 250 years, beginning with the surprise sack of Northumbria's Lindisfarne Priory in 793 AD, the Viking Age propagated terror, dis- seminated people and culture, and reshaped the boundaries of the known world. Then, with the serial defeats in 1066 of Norway's Harald Hardrada at Stamford Bridge in Yorkshire and Harold Godwin- son at Hastings in Wessex, the Viking Age snapped abruptly to a close. As if frozen in their places, the Northmen — Norse, Nor- mans — found themselves in control of a huge swathe of the globe, stretching even then from the Baltic Sea in the east to the Gulf of St Lawrence in the west.

It is to the credit of the curators, Dr William Fitzhugh and his assistant Elisa- beth Ward, that their Viking exhibition (at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC, until 13 August) succeeds in demol- ishing glib stereotypes even while clinging to one in the very title of this installation. `Vikings', strictly and etymologically speak- ing, were men — older boys, in most cases, `of the va, or bay' (note Iceland's Reyk- javIk today) — whose hooligan tempera- ments gravitated towards piracy, rapine and pillage. Not all Northmen and women went a-viking; but when the technically advanced longboats (the cruise missiles of their day) returned laden with loot and lore from places previ- ously unknown, a combination of enterprising spirit and simple curiosity lured settler families onto the waves in humble, full- bodied merchantmen, or knorre.

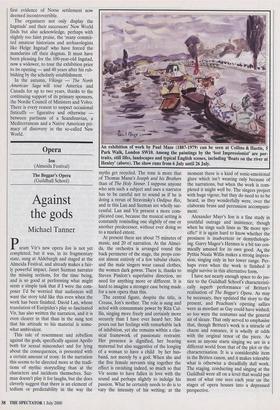

The Smithsonian exhibition certainly indulges a visitor's preconceptions of Vikings as an undiluted warrior race. Dis- plays of still impressive arms; spoils from Russia, Europe, Byzantium and North Africa; cultic figurines of warrior gods King Olaf Kyrre penny, found in Maine sustain the stereotype. So do illuminated manuscript pages bewailing 'the fury of the Northmen'. The 9th-century Lindisfarne Stone, which Great Britain has loaned abroad for only the second time, depicts the infamous raid as a horrific presenti- ment of an abject Day of Judgment. In the show's delightful catalogue raisonne, the Flemish Annals of St Vaast (884 AD) are culled for evidence of the Vikings' success Ivory mediaeval chess pieces, found on the Isle of Lewis in achieving the image they most desired:

The Norsemen continued to kill and take Christian people captive, destroy churches, tear down fortifications and burn towns ... There was no highway or village where the dead did not lie, and all were filled with torment and grief to see the devastation of the Christian people, driven to the point of extermination.

A terrified Church, however, was under- standably unlikely to heed the coeval accomplishments of Norse discovery and settlement of Ultima Thule. While Dark Age Christian literates established a Viking persona that would persist for the next 1,200 years, modest, illiterate working farmers, merchants and their families marched across the North Atlantic in man- ageable steps of 250 nautical miles or so from Norway to the Orkneys to the Faroes to Iceland to Greenland to North Ameri- ca's Helluland, Markland and Vinland (today's Baffin Island, Labrador and New- foundland) — all the way before the last millennium had begun. A particular finesse of this show is its ability to distract the browser unconsciously away from the Sturm and Drang of bloodthirsty hooligans and towards more fundamentally impres- sive feats of prosperity in alien wastes. Hovering amidst wrought, jewelled, cast, forged, carven, woven, graven and limned artefacts of daily life and culture, it is the benign ghost of the shadow child that haunts the visitor long after images of Viking terror have receded.

One can easily imagine oneself on board alongside Bjarni Herjolfsson in 985 AD on his chronicled passage from Iceland to Greenland for the rather mundane purpose of wintering with his father. Blown astray, he coasted Marldand but feared to stay. It was Lief Eriksson who mocked him for his timidity by retracing his voyage and, it is thought, establishing the first European settlement in the Western Hemisphere at L'Anse aux Meadows, facing the Strait of Belle Isle, c.1,000 AD.

In 1961, it was an entrenched archaeological establishment that mocked the Norwegian husband and wife team of Helge and Anne Stine Ingstad for first proposing that Vikings may have settled on purpose in North America. Like Heinrich Schliemann at Troy and Sir Arthur Evans at Knossos, the Ingstads applied their interpre- tations of ancient texts — Ice- landic sagas in particular — to a painstaking process of exca- vation before turning up the first evidence of Norse settlement now deemed incontrovertible.

The organisers not only display the Ingstads' and their successors' New World finds but also acknowledge, perhaps with slightly too faint praise, the 'many commit- ted amateur historians and archaeologists like Helge Ingstad' who have forced the mandarins off their dogmas. It must have been pleasing for the 100-year-old Ingstad, now a widower, to tour the exhibition prior to its opening — and 40 years after his rub- bishing by the scholarly establishment.

In the autumn, Vikings — The North American Saga will tour America and Canada for up to two years, thanks to the continuing support of its primary sponsors, the Nordic Council of Ministers and Volvo. There is every reason to suspect occasional fisticuffs — figurative and otherwise between partisans of a Scandinavian, a Mediterranean and a Native American pri- macy of discovery in the so-called New World.

Previous page

Previous page