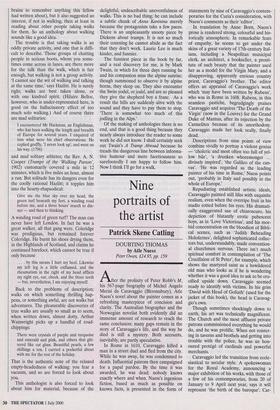

Walking and talking

P. J. Kavanagh

THE VINTAGE BOOK OF WALKING edited by Duncan Minshull Vintage, £8.99, pp. 340 Many years ago my friend Jaspistos (now competition provider for this maga- zine) asked me to walk with him in the Welsh hills. I enjoyed it, and so began a series of walks taken with him, or with another friend, which culminated (too grand a word) in walking the River Severn from estuary to source, a little bit each year. I reported on this walk, once a year, when I wrote a weekly column for this paper: one out of roughly 50 annual columns. But when I met Spectator readers they almost invariably said, 'When are you going on another of your walks?' I knew this to be ordinary politeness (racking their brains to remember anything this fellow had written about), but it also suggested an interest, if not in walking, then at least in reading about other people taking walks for them. So an anthology about walking sounds like a good idea.

The trouble is that taking walks is an oddly private activity, and one that is diffi- cult to describe. Those groups of chatting people in serious boots, whom you some- times come across in lanes, are there more for the talk than the walk, which is fair enough, but walking is not a group activity. `I cannot see the wit of walking and talking at the same time,' says Hazlitt. He is surely right; walks are best taken alone, or with one kindred spirit. (Hilaire Belloc, however, who is under-represented here, is good on the hallucinatory effect of too much solo walking.) And of course there are mad solitaries:

I encountered Mr Hackman, an Englishman, who has been walking the length and breadth of Europe for several years. I enquired of him what were his chief observations. He replied gruffly, 'I never look up', and went on his way. (1796)

and mad solitary athletes; the Rev. A. N. Cooper (Tramps of the 'Walking Parson', 1902) customarily covered a mile in 12 minutes, which is five miles an hour, almost a run. But solitude has its dangers even for the coolly rational Hazlitt; it topples him into the hearty-rhapsodical:

Give me the blue sky over my head, the green turf beneath my feet, a winding road before me, and a three hours' march to din- ner — and then to thinking.

A winding road of green turf? The man can never have left London. In fact he was a great walker, all that gang were. Coleridge was prodigious, but remained forever Coleridge. He burnt his shoes drying them, in the Highlands of Scotland, and claims he continued barefoot, which cannot be true if only because . . . by this means I hurt my heel. Likewise my left leg is a little enflamed, and the rheumatism in the right of my head afflicts my right eye, ear, cheek, and the three teeth — but, nevertheless, I am enjoying myself.

Back to the problems of description; walks on which something thrilling hap- pens, or something awful, are not walks but adventures. The pleasurable discoveries of true walks are usually so small as to seem, when written down, almost dotty. Arthur Wainwright picks up a handful of road- chippings:

There were crystals of purple and turquoise and emerald and pink, and others that glit- tered like cut glass. Beautiful pearls, a few shillings a ton. I carried a pocketful about with me for the rest of the holiday.

That is the authentic note of the relaxed empty-headedness of walking: you fear a vacuum, and so are forced to look about you.

This anthologist is also forced to look about him for material, because of the delightful, undescribable uneventfulness of walks. This is no bad thing; he can include a subtle chunk of Anna Karenina merely because the protagonists take a few paces. There is an unpleasantly snooty piece by Dickens about tramps. It is not so much their cozening he cannot abide as the fact that they don't work. Laurie Lee is much kinder, and funnier.

The funniest piece in the book by far, and a real discovery for me, is by Mark Twain, in which for three days running he and his companion miss the alpine sunrise; though summoned to observe it by alpine horns, they sleep on. They also encounter the Swiss yodel, or jodel, and are so pleased they give the shepherd boy a franc. As a result the hills are suddenly alive with the sound and they have to pay them to stop. `There is somewhat too much of this jodling in the Alps.'

Of the making of anthologies there is no end, and that is a good thing because they nearly always introduce the reader to some work he did not know. I shall certainly seek out Twain's A Tramp Abroad because he treads the dangerous line between informa- tive humour and mere facetiousness so surefootedly I am happy to follow him. Now I think I'll go for a walk.

Previous page

Previous page