Wine

The Parker effect

Andrew Jefford A'parasitical activity' is how the candid Oxford Companion to Wine describes wine writing. Wine writers themselves rarely contest the appellation; most began the business of money-earning in some far less agreeable field, and are prepared to settle for any amount of opprobrium so long as no one admonished them to return prompt- ly to the office after a mineral-water lunch.

These dropsical cuckoos have prospered in the last decade, spurred on by the grow- ing fortunes, glittering fame and swelling power which has attended the 'democrati- sation' of wine-drinking. The outcome, unsurprisingly, is scission. Deep disagree- ments have arisen among the most pre-emi- nent in the profession as to what the job consists of, and how it should best be done.

Hugh Johnson is the Great Writer: a man who combines lyricism and conciseness with a genuinely encyclopaedic mind. The Johnson philosophy is one of cultured mul- tiplicity and historical integrity: the diversi- ty of wine, he argues, is its joy. Jancis Robinson is the Great Educator: a fine taster, an accomplished journalist, a supremely intelligent assembler and then disseminator of complex information. Robinson dislikes axe-grinding; her philos- ophy is a simple exhortation to understand- ing and enjoyment. Oz Clarke is the Great Enthusiast: a taster-performer, writer and populariser every bit as intellectually gifted as Johnson and Robinson, though the inanities of Food and Drink (the television programme for which he is best known) occlude many of his talents. Philosophical- ly, Clarke is an excitingly radical libertarian for whom no precedent or reputation sur- vives without sensual justification in the glass.

And then there is the man from Mary- land, Robert Parker: the Great Critic. Of the four, Parker is the most revolutionary, since he has challenged the basis of all pre- vious wine writing, which was that excel- lence in wine can be dismissed but never pinpointed. Parker pinpoints, by giving wines scores out of 100. He argues that objectivity in wine assessment is possible. Many wealthy wine collectors and investors subscribe to his newsletter and his views; they subscribe, moreover, to the notion that Parker's scores are correct, definitive and final assessments of the quality of wine, even though Parker himself cautions against this and revises scores from time to time.

The literal-minded acceptance of Parker verdicts has had shattering commercial implications, since Parker's scores now make the market in young fine wine, to the great good fortune of some wine producers and the bitter chagrin of others. Parker's scores have, moreover, greatly facilitated investment (or, to the vinously correct, speculation) in fine wine, though Parker claims that he 'totally disapproves' of this.

Parker has criticised other wine writers, particularly British ones, for ethical dubiety (he alleges that the hospitality and gifts of wine producers have been traded in return for affectionate copy), lack of global tasting experience, and conflicts of interest (both writing about and having various commer- cial involvements in wine). Parker, mean- while, has been criticised by both Johnson and Robinson for allowing what they see as the spurious precision of his scores to impoverish the wider appreciation of wine's beauty.

In many ways, Clarke and Parker are close in approach, since both take the view that physical pleasure — scent in the nos- trils, flavour in the mouth — is the alpha and omega of wine appreciation. Yet they certainly taste differently: Clarke, for exam- ple, is a great advocate of the wines of New Zealand, both white and red, whereas Park- er reserves some of his most rancorously barbed invective for these, damning all the country's red wines as 'grotesque' and most of its Sauvignon Blanc as 'ferociously vege- tal and washed out'. He states, too, that `the lavish press' which New Zealand has received 'from the English wine media' looks, from Maryland, suspiciously like the consequence of free journalists' visits.

In print, then, Parker (a former lawyer) appears severe, irascible, unforgiving. In the flesh, by contrast, this full-bodied man has the slightly chaotic charm of the enthu- siastic schoolboy. There is no pomposity or pretension to him, merely an innocent halo of self-certainty.

He feels that his mixed reception in Britain so far has been due to a misunder- standing about roles. 'I am actually a critic in the true sense. Hugh Johnson is a mar- vellous writer and he's written a number of books which are an extraordinary legacy to all wine-lovers, but Hugh is not a critical person.'

Johnson would disagree, of course: he criticises Germany's politically craven wine legislators; he criticises geographically neu- tral wines (the growing pool of Chardon- nays and Cabernets whose flavour reflects varietal characteristics rather than regional ones); he criticises the lack of perspective of British supermarket wine buyers. These are issues. What Johnson does not general- ly do is damn specific wines because he does not like them; he conceives that (in the case of most sound wines) someone might like them, and attempts to under- stand and give words to the qualities which might make them likable. Parker's premise is that it is the critic's duty to taste, judge, praise — or damn.

Parker damned both what he considers poor wines and the practices which lead to poor wine-making when I met him this March on his first visit to London for ten years. The wines which I really do stand against and deplore are the denuded, ster- ile, insipid wines that are the consequence of modern-day oenology and so-called progress in wine-making. There's an inher- ent conflict between the objectives of oenology and the objectives of the con- sumer. The 1947 Cheval Blanc is the great- est wine of the century. I don't know one oenologist in Bordeaux who would allow that wine to happen today: it's made from overripe grapes, it has volatile acidity, it has residual sugars, it's too rich; frankly it's too good.' Filtration is a particular dislike. `When you're talking about a great estate, where the wine falls brilliantly naturally, where it's completely healthy, why would you filter? There is absolutely no risk. Why do famous châteaux routinely filter? There is no excuse.'

Parker's campaigning on this issue has, unquestionably, improved the quality of much fine wine, even though the motives of producers in discarding their filter pads may be more to do with the elevation of their Parker scores than the quest for per- fection. Parker also campaigns for lower yields and organic cultivation, and against chaptalisation (sugaring to raise alcohol levels) and acid-adjustment of wines. All of these measures, assuming they are imple- mented truthfully and competently, will lead to better (and more expensive) wine.

Parker's campaigning is more controver- sial when, implicitly rather than explicitly, he urges producers to make wines of the style he particularly enjoys. Any concor- dance of his wine descriptions for wines gaining over 95 points would reveal words like 'voluptuous', 'opulence', 'blockbuster', `power', 'lavishly ripe' and so on, often with (in the case of red wines, at least) mention of soft tannins and low acidity. Some allege that Parker is oak-obsessed. This criticism is often based on Parker's extravagant praise of the Rhone producer Guigal (`this planet's greatest wine-maker'), who uses lavish new oak for aging his wines in a region where older, well-seasoned oak was traditional. Careful reading of Parker's reviews, however, reveals that he regularly criticises wines (such as New Zealand's Chardonnays) on which oak is obtrusive, though he certainly enjoys the sheen it can bring to an already richly constituted wine.

Richness, finally, is the key: Parker loves richness and wealth of flavour. He casti- gates the 'misinformed emphasis on a wine's high acidity and structure'. The result is that many of the world's greatest wines are tending to soften and fill out in contrast to their forebears.

Good or bad? Rich wines are certainly easy to enjoy, and richness is always the hallmark of evidently fine vintages like 1982, 1989 and 1990 in Bordeaux, or 1990 in Burgundy. Richness does not exclude subtlety. The difficulty comes with vintages like 1988 in both Burgundy and Bordeaux, where opulence is obliged to take the pas- senger seat and structure moves over behind the steering wheel. Parker feels the 1988 Burgundies have been overrated, `above all [by] the English press (who judge Burgundy as if it is Bordeaux)'. British authorities like Anthony Hanson counsel patience for these wines — but Parker doesn't believe Burgundy ages well. The case remains open. What is certain is that there is a tradition in British (and Euro- pean) wine appreciation of enjoying not only nuance and understatement in wine, but also firmness, singularity and even the more austere forms of beauty; yet these words are as rare as winter butterflies in that concordance of terms for 95-point-plus Parker wines.

Parker has not only influenced wine- making, he has also influenced wine writ- ing. He is the first person to base a whole career on pure criticism, the reviewing of wines, and his dazzling success has spawned numerous imitators in wealthy America, and is beginning to do so in relatively impoverished Britain. The best aspect of Parker's influence on other writers is that he has created a precedent for profession- alism, integrity, thoroughness, and brought about a healthily adversarial climate. Writ- ing to the order of wine-producers, though it still occurs in certain publications, is on the wane.

More nefarious is the notion that the reviewing of bottles might be the highest calling of the wine commentator. Wine writers fuss more about their tasting abili- ties nowadays then their writing skills. This has already created a tide of tedium in wine writing generally, yet because such reviews have a specious appeal to the neophyte they find a ready market. Oz Clarke is the one writer with the verbal fecundity to make the reviewing of supermarket wines into occasionally diverting copy — and hence spark the drinking imagination, the true calling of the wine writer.

The author of the best selling Superplonk, Malcolm Gluck, plays a mildly amusing Caliban to Parker's Prospero, lavishly inflated, wordy attention and scores out of 20 for inexpensive and transient wines. Parker's own writing, indeed, is of little lit- erary interest, though in analytical terms it is highly intelligent. No one reads Parker for the pleasure of the text; they read him for definitive verdicts. The market in defini- tive verdicts, is of necessity, limited — to Parker.

The Great Critic is a sort of genius among tipsters, and we all need tips. Yet anyone who drinks thoughtfully will know that wine is the most wily of mistresses, the most artful of lovers, apt at any moment to surprise, frustrate, delight, trick and tease. Parker has fought his way into the arms of wine, and his kiss-by-kiss account is of cer- tain and evident value; yet his is not the only way, his mouth not the only mouth, and those who would enjoy wine to the full must locate and pursue their own fluid desires.

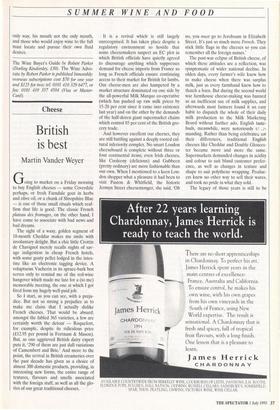

The Wine Buyer's Guide by Robert Parker (Dorling Kindersley, £30). The Wine Advo- cate by Robert Parker is published bimonthly: overseas subscriptions cost $70 for one year and $125 for two; tel: 0101 410 329 6477, or fax: 0101 410 357 4504 (Visa or Master- Card).

Previous page

Previous page