CAN'T TAKE IT ANY MORE'

William Cash talks to members of

the O.J. Simpson jury, and discovers why the murder trial might never be concluded

Los Angeles NO AMOUNT of frequent flyer bonus miles will get you a room on the fifth floor of the Hotel Inter-Continental in down- town Los Angeles. The official line is that the suites are taken up with a 'conference'. Press the number 5 in the lobby lift and nothing happens.

When a floor is closed off at a luxury hotel, it usually means that access is limit- ed to 'privileged guests' with a special lift pass to the 'Club' floor. As you step out of the lift, such guests — whose expense accounts won't flinch at being hit for an extra $100 a night — are greeted by a smiling 'hostess-concierge', with a glass of champagne on a silver salver, guarding the entrance to VIP executive freebie-heaven.

Take the Inter-Continental service lift to the fifth floor, and the welcome is notably different. Two heavily armed and very well-fed white Los Angeles sheriff deputies are seated behind a table stacked with CB radios and a bank of television monitors. A mounted camera swivels over- head.

Although the jury for the O.J. Simpson trial are sequestered at an 'undisclosed hotel', it is not the best-kept FBI secret that for the past eight months the panel has been staying in the style to which most — currently composed of nine urban blacks, two whites and a Hispanic — are certainly not accustomed at the de luxe Hotel Inter-Continental. Holder of a three- diamond award for excellence, a standard room is $160 a night. As Dominick Dunne, covering the trial for Vanity Fair, told me at a recent party, 'The jury are having the time of their lives.'

Or are they? With ten members of the world's most famous jury panel having already been dismissed, and an increasing likelihood of a possible mistrial because of the panel's rapid rate of attrition — there are just two left: one black, one white such a theory clearly needs testing. Back in April, a 25-year-old flight attendant Tracy Hampton was relieved of duty after plead- ing to Judge Ito, 'I can't take it any more.' She spent the next week recovering in a mental hospital.

Last weekend, having secured a fourth- floor room a few doors down from the jurors' dining-room and health club, I sub- jected myself to the five-star 'prison' condi- tions that the removed jurors have groaned so much about.

The Inter-Continental is three years old, the newest hotel in LA, built on earth- quake-proof roller-skates and adjacent to the LA Museum of Contemporary Art and the fiercely ethnically correct 'performing arts centre' called California Plaza. The glass atrium lobby is dominated by a 25- foot-high 'Yellow Fin' sculpture by David Strohmeyer which, as the hotel brochure puts it, 'majestically welcomes guests from its glass cradle'.

On the face of it, the jury seem to be pampered rotten. Their bill is already around $500,000. They have maids, their laundry is returned in a bundle with a neat bow. Hotel facilities include the usual 85- degree swimming- pool, piano bar — with 25- or 12-year-old Macallan — and even a choice of stuffing in your pillow. Just in case you can't face a morning visit to the gym, there's a 'Healthy Lifestyle' In-Room Private Dining breakfast called 'The Cali- fornia Plaza Work-Out'. It boasts carrot juice, sliced berries and four types of toast (seven grain, whole wheat, raisin or cinna- men). Bedside-drawer reading is either the King James Bible and/or The Teachings of Buddha.

Unfortunately, however, as I learnt after tracking down a number of the dismissed jurors at their homes, life behind the sher- iffs desk of the fifth floor enjoys no such `guest privileges'.

In fact, the jury seem to have no idea that they are staying in a five-star hotel. One ex-juror told me she thought she was staying at a Holiday Inn. In eight months, they have never seen the lobby or been allowed to talk to other guests. Their tele- vision aerials and radios have been discon- nected, their phone calls are rationed and monitored. They are not allowed room ser- vice. Their newspapers — USA Today and the 4A Times — arrive in shreds, with all references to O.J. Simpson cut out.

None of the jurors has been allowed a drink for eight months. Family members who visit on Wednesdays and at weekends are searched for alcohol. Smoking is strict- ly controlled. All conversations with other jury members at meal times are monitored by LA sheriff deputies. Almost the only hotel amenity the panel are able to share with other guests is playing in-room video games.

The most widely agreed view of the O.J. Simpson trial is that it will end in a hung jury, or possibly a mistrial, not so much because of any evidence heard in court but because of a combination of acute psycho- logical and racial tensions (to a lesser extent now that the panel is overwhelm- ingly black) that have built up between jury members. Cut off from the outside world, most of the panel have little or nothing in common; except the case, which they are not allowed to talk about. Cliques, have grown, people violently hate each otr and they seem unable to agree on even the most trivial subjects.

As each new jury member is dismissed, more disturbing evidence leaks out that their tempers are close to breaking point. Jeanette Harris, a 38-year-old black job counsellor dismissed in April after she failed to cite an alleged incident of domes- tic abuse in her questionnaire told me, `The real problem is if they can make it to the end. They just want to go home. They've had enough.'

Their day begins with a 'boot-camp' style morning call shortly after 5 a.m. (they are locked inside their rooms at 11 p.m., handing over their keys each night). Breakfast is at 5.30 a.m., dinner 6 p.m.

The whereabouts of the jurors' dining- room is a supposed secret. Early on Satur- day morning, however, while lurking in my towelling robe outside the health club, I met the jury emerging from a dining-room suite called The Grand Room, a few doors down from my own. The black human crocodile was led by a wiry-looking young black guard in a navy-blue bomber-jacket with a walkie-talkie (called Russell). The door was left open. The buffet-style din- ing-room comprises three conference tables with green and orange tablecloths.

According to the most recently released black juror Willie Craven — part of the reason for his dismissal was for staring at a white female co-juror in the elevator — the dining-room was almost a throwback to the days of segregation. I talked to him on the lawn by his bungalow in the lower-middle- class black neighbourhood of Carson. Just back from church, he wore an easy-press black pinstripe suit and shiny black shoes.

In the early months, he said, before most of the white jurors were dismissed, 'the• tables in the dining-room were nearly always separated by race'. The blacks always lined up first and took over one table. 'There was usually a place left at the white table, so I used to make a point of sit- ting there to force somebody to sit some- where else. The next day I come in and the places are like reserved. There's a jacket there, and a purse or hat on another seat, so I went back and sat on the other table.

`There are factions between individuals who seem racist,' he added. 'There's racial problems between people. This sequestra- tion thing is the problem. Judge Ito had no idea what a juror goes through. Some of the jurors cry. The longer you are sequestered the longer you are isolated and some people crack.' He said that a young black woman he knew was on the point of breakdown.

The jury members, he said, are like a bickering, dysfunctional family. Simply choosing which videos to watch has proved such a personality battleground that an additional television-room had to be creat- ed. Whites and blacks often sit in different rooms. 'The thing about movies,' he said, is that black people and white people as a rule have a different sense of humour. Shows that I like to watch, not a lot of white people like them.'

Such problems were confirmed by Jeanette Harris, whom I spoke to outside her small first-floor apartment, flaking with crumbling blue paint, near LAX air- port in Inglewood. She, again, said that the movie-room was the scene of various angry rows. 'I remember once we were watching this movie, and people were putting their feet up on the seats and talking during the film, and it ended up as this big, explosive argument and one of the jurors — a white woman — started screaming and ran out and got the sheriff. I mean we couldn't even converse as adults.'

To alleviate the pressure, various 'out- ings' were arranged. These included a trip on a luxury yacht to Malibu, a visit to a Laker's basketball game, a piano concert, a visit from the comic Jay Leno and an evening at the musical Miss Saigon. But they seem to have done little to ease the frustrations. The group factions, says Har- ris, are so bad that on an 'outing' to Mari- na Del Rey, one mini-bus was crammed with around 13 people whilst the other had just six. 'Some people just wouldn't sit in the same van with others. In the end, they had to pull up and force people to move into the other van because it just wasn't safe.'

I asked whether, when it came to delib- erations, she thought the remaining whites or blacks had stronger personalities. 'Both sides are strong. Very strong. I can't imag- ine what it will be like when it comes to deliberations. That will be very interesting. Choosing the foreman will be real interesting too.' The leading candidate jockeying for the job is, believed to be an elderly white woman.

The most blatant instance of racial or personality conflict, said Harris, concerned the use of the health club. To begin with jurors were allowed to use the hotel gym on the fourth floor — near my room — at 10 p.m., after it was closed to hotel guests. Then a feud broke out 'because some of the white jurors had a problem with us going to the gym with them. They wanted two shifts. This one white woman (described as the "ringleader", and still on the jury) said, "Well, we were thinking it might be best if you guys go at 11 p.m. and we go at 10 p.m." ' On another occasion, Harris told me a 63-year-old white British-born jury mem- ber — Catherine Murdoch — violently shoved her off the pathway whilst they were exercising. 'It just really shocked me,' she said. 'She just deliberately walked in front of me and pushed me. About an hour later, after I had calmed down, I said, "I don't appreciate being pushed," and she told her friends who went around making sly remarks when they were near me: "Oh excuse me, Jeanette . . . " ' Was this light-hearted joking?' I asked. 'No. It was very bitter. Very bitter.'

Such instances highlight the major prob- lems of sequestration in media show trials in America. Little research has been done into how to make jurors cope with their ordeal; as Carolyn Walters, the jury fore- man of the sequestered jury on the Regi- nald 0. Denny beating trial said afterwards, 'When you go into that jury room and begin deliberating, you begin to see who you are holed up with. People you thought you were friends with — you want to kill them.'

Behind the television cameras, the sup- posed 'trial of the century' has deteriorated into a shambolic backroom farce on the fifth floor of a hotel that few of the jurors would ever have expected to visit, let alone be locked up inside for a possible year.

The plight of jurors has become so dire in New York State that a special panel has been created to propose changes, like abol- ishing mandatory sequestering and increas- ing jury pay. Los Angeles — despite its record of media show trials — has no such plans. Jury pay is a risible $5 a day.

As a result, jurors may rush to a verdict in the desperate hope of being able to live a normal life again. Personal animosities frequently spill over into obduracy and stubbornness that result in jury deadlock.

The double murder trial of the Menen- dez brothers — who both admitted to gun- ning down their parents at their mansion in Beverly Hills — ended in a mistrial after six months, millions in legal fees, and `severe divisions' between two separate juries. 'It was hostile in there,' said Tracy Miler, a 27-year-old female jury member afterwards.

`There were insults, sexual comments. The men tried to outshoot us.' The current O.J. jury has ten women and two men.

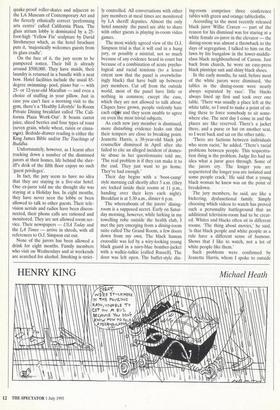

On Sunday afternoon, after speaking with Craven and Harris, I parked my car behind the Jaguar Sovereign in the gently sloping driveway of Catherine Murdoch. The 63-year-old retired legal secretary lives in Prosser Avenue, a prosperous resi- dential street in LA's affluent Westside. She was dismissed because she was found to share the same arthritis doctor — an Englishman with `very expensive' fees with O.J. Simpson.

Originally born and brought up near Loch Lomond, Mrs Murdoch married her Australian husband, Ray, in the 1950s. A small woman with frizzy white hair, she hardly seems like the sort of person who goes around shoving a robust-looking 38- year-old black woman. She said she never touched Jeanette Harris. `Why would I bother hitting somebody intentionally? Even if I had brushed past her, I would have said I was terribly sorry.'

Husband Ray quickly added, `I wouldn't pick on Jeanette Harris, and I'm bigger than her. I think she's the racist type not my wife.' Although Mr Murdoch him- self isn't 100 per cent sure that O.J. is a intrderer, 'my friends down the tennis club all say he did it'.

William Cash writes from Los Angeles for the Daily Telegraph.

Previous page

Previous page