Opera

To Italia

By DAVID CAIRNS

GRANTED the congenital On paper, Milan appeared to have several ad- vantages over London. The native resources of the company are so rich that it was able to find a splendidly sonorous baritone and bass for the tiny sentries' duet in Act 5 and a singer as mag- nificent as Fiorenza Cossotto for the minor role of Ascanius. Giulietta Simionato is a better singer than either of the mezzo-sopranos who have played Dido at Covent Garden, and as Cassandra Nell Rankin, whose voice has developed strik- ingly since she last sang in London, has the quality if not the edge over Amy Shuard. Miss Wallmann may not be a great producer, but in the handling of massed effects she is usually as competent and decisive as Sir John Gielgud, in Opera at least, is fumbling and irresolute. And in Kubelik La Scala had a conductor who plainly loves the music and probably knows it as well as any musician in Europe. Yet the Product of all these talents is frustration, cold- ness, mediocrity, only momentarily shot through with beauty and grandeur. It is true that La Scala avoids the grosser blunders of the Covent Garden production. Mercury is not the hermaphrodite apparition from Ascot with whom we are so wearily familiar in London. The ghost of Hector does not stand obstinately in front of the footlights like a hat-stand, but swims slowly into con- sciousness in a huge circular-mirror hanging at the back of /Eneas's tent; the device is not wholly successful, but it is an intelligent attempt. In the Temple of Vesta Miss Wallmann correctly observes the first rule of all opera production: never let the players of minstrels' harps pluck in time to the quick beats of the music, if you do not wish them to look ridiculous. Although the Greek soldiers run their Covent Garden rivals close in point of sheer gormlessness, the scene as a whole is much more impressive. Here, and in the episode of the Trojan Horse, with the flaming torches of the procession approaching from an immense distance, the depth of the Scala's stage is used with grand effect. Where the production goes wrong is in decid- ing on a high degree of formalism and then failing to get either the chorus or the principals to act with the conviction necessary to sustain it. Realism in opera can succeed at a much lower level of art than stylisation. The garden scene is not brilliantly produced at Covent Garden, but it makes its point; at Milan one is not made to feel that any great emotional and moral issues are involved—the passion and the poignancy of the scene, pass one by, because Dido and eEneas remain puppets, actors lacking the power to bring their frieze-like setting alive. Equally, the monu- mentality of Piero Zuffi's sets is largely nega- tive, without warmth, grace or energy. In conse- quence it is left to the music to project The Trojans as drama, as distinct from mere spec- tacle; and it is just here that the Milan per- formance is weakest.

The quality of orchestral sound is wonder- fully rich and deep, but it is too Wagnerian; that almost wiry clarity characteristic of Berlioz's scoring is lost in lushness, and many vital details, like the flute's reiterated C in the Septet, dis- appear without trace. Both Simionato and Rankin make some fine noises, but phrase after phrase betrays their incomprehension of the style and deeper significance of their music. For about seventy seconds Mario del Monaco is a stupendous kneas; hurtling from the back of the stage like a young bull, black-bearded and bale- ful, uncompromising, menacing, the voice a trumpet minim spargens sonu►n, his narration of the death of Laocoon staggers the imagination; whereupon, at the performance which I saw, the great tenor proceeded to retire to a throne at the side of the stage, where he sat out the eighty bars of ensemble before his next solo entry with heroic fortitude. Miss Cossotto's vanity, though more disarmingly naïve, was hardly less ex- travagant. That she is a superb artist in the making she lately proved at the Festival Hall in Verdi's Requiem; but, as Ascanius, her smiling determination never to demean herself below a stentorian forte, even in the Septet, wrung an anguished hiss from Kubelik, who reminded me, at his curtain call, of Pepys's description of Major-General Harrison being hanged, drawn and quartered at Charing Cross: 'he looking as cheerful as any man could do in that condition.' It is hard to believe that so sensitive a musician can have willingly agreed to cuts as extensive and brutal as those imposed at La Scala; they in- clude lopas's song, the duet of Anna and Narbal, the Andante of fEneas's aria, several ballets, numerous minor lacerations and- chatiment efiroyablel—fifty mortal bars out of the love duet.

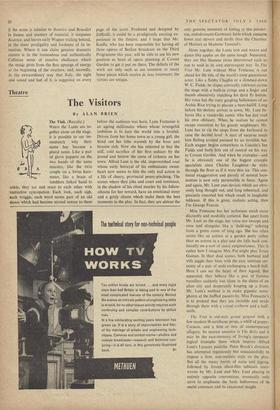

In England we at least give Berlioz's notes the benefit of the doubt. Last Sunday's broadcast performance of Benvenuto Cellini (conducted incisively and efficiently by Antal Dorati, played with splendid élan by the LSO and sung by a reasonably competent cast) faithfully followed the revised, Weimar version except for a single insignificant cut. Ironically, there is a case for performing Cellini in some form other than that finally approved by Berlioz. In agreeing to Liszt's alterations he may have been impelled by an overriding desire to have his opera staged again after fourteen years'. neglect. The original librettists who shaped Berlioz's ideas for the Paris stage were amateurs; but so were the librettists who took in hand the revival at Wei- mar. No honest admirer of Berlioz ought to baulk at admitting that in point of consistent dramatic realisation of its theme, as well as in theatrical cohesion, Benvenuto Cellini is no masterpiece. There is a certain frivolous aimlessness about some of its episodes. It lacks the concentration of intellectual fibre which distinguishes even a work as uninspired as Tannlaiuser. Yet such is the vitality of the music that this lack of dramatic profundity seems unimportant. Berlioz thought he had never again found 'such verve and Cellinian impetuosity, such variety of ideas'; and if the score is inferior to Beatrice and Benedict in finesse and mastery of material, it surpasses Beatrice, and leaves early Wagner trailing behind, in the sheer prodigality and freshness of its in- vention. Where it can claim genuine dramatic stature is in the tremendous and authentically Cellinian sense of creative ebullience which the music gives from the first upsurge of energy at the beginning of the overture, and, secondly, in the extraordinary way that Italy, the sight and sound and feel of it, is suggested on every page of the score. Produced and designed by Zeffirelli, it could be a prodigiously exciting ex- perience in the theatre, and I hope that Mr. Keeffe, who has been responsible for having all three operas of Berlioz broadcast on the Third Programme this year, will be able to use his new position as head of opera planning at Covent Garden to get it put on there. The defects of the work are only such as are common to many lesser pieces which receive de luxe treatment; the virtues are unique.

Previous page

Previous page