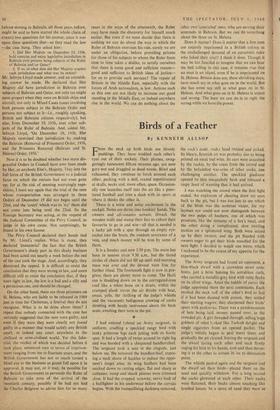

Birds of a Feather

By KENNETH ALLSOP FROM the neck up both birds are bloody puddings. They have winkled each other's eyes out of their sockets. Their plumes, swag- geringly tumescent fifteen minutes ago, are now gory-wet and draggled as dead weeds. Blind and exhausted, they continue to lurch around each other, pecking with a dull, crazed repetitiveness at skulls, necks and, more often, space. Occasion- ally one launches itself into the air like a punc- tured football and tries a slash with its spurs at where it thinks the other is.

There is a tense and noisy excitement in the cockpit. Notes are thrust into bookies' hands. The owners and alk;onados scream, thwack the wooden walls and stamp their feet to exhort their favourite to go in and win—all that is needed is a lucky jab with a spur through an empty eye- socket into the brain, the random severance of a vein, and much money will be won by some of them.

It is a Sunday and now 3.50 p.m. The main has been in session since 9.30 a.m., but the tiered circles of chairs did not fill up until mid-morning mass was over and the devout were free for further ritual. The fourteenth fight is now in pro- gress; there are plenty more to come. The Haiti sun is thudding doWn on to the corrugated-iron roof like a white bone on a drum; within the cramped plank circus the air throbs with heat, sweat, yells, the shrilling of the judge's whistle and the vacuously belligerent crowing of cocks strutting with beady restiveness about the back seats, awaiting their turn in the pit.

I had entered behind an Army sergeant, in uniform, cradling a speckled rangy bird with lanky primrose legs each jutting with its horny spur. It had a length of twine around its right leg and was hooded with a chequered handkerchief. The sergeant took a seat at the ringside, just below me. He removed the handkerchief, expos- ing a neck shorn of hackles to reduce the oppo- nent's target area; its wing feathers had been snicked down to cutting edges, flat and sharp as cutlasses; rump and shank plumes were trimmed close. It had the cropped. scrawny, nervy look of a bullfighter in his underwear before the corrida begins. With the tranquillising darkness removed, the cock's nude, snaky head twisted and jerked. Its bleary, feverish air was probabty due to being primed on meat and wine. Its ears were assaulted by the racket, by the roars from the crowd and by the befuddled war-cries of other cocks, one challenging another, The speckled gladiator opened its thin melancholy beak and released a raspy hoot of warning that it had arrived.

I was watching the crowd when the first fight ended. An explosion of cheering drew my eyes back to the pit, but I was too late to see which of the birds was the nominal victor, for my layman eye could not now distinguish between the two pulps of feathers, one of -which was prostrate, like the remains of a fox's meal, and the other doing a complicated, slow twirling motion on a splintered wing. Both were seized up by their owners, and the pit flooded with owners eager to get their birds matched for the next fight. I decided to watch one more, which I reckoned to be the extent of my appetite for the experience.

The Army sergeant had found an opponent, a blue-black dwarf with a crownless straw som- brero, just a brim haloing his astrakhan curls, who carried a metallic-grey bird with rusty flecks on its silver wings. Amid the babble of patois the judge appointed them the next contestants. Each stroked the neck ruff of the other's bird to feel if it had been daubed with poison, they settled their starting wagers; they sharpened their birds' spurs with penknives. There was a pandemonium of bets being laid, money passed over, in the crowded pit. A girl threaded through, selling huge gobbets of what lc oked like Turkish delight and single cigarettes from an opened packet. The judge's whistle began to peal many times and gradually the pit cleared. leaving the sergeant and the dwarf facing each other and each firmly caging his bird in his hands, now and then thrust- ing it at the other to arouse its ire to detonation point.

The whistle pealed again and the sergeant and the dwarf set their birds—placed them on the sand and quickly withdrew. For a long second the cocks glowered at each other. Their necks were flattened, their beaks almost touching like levelled lances. In a spray of sand they were at it, jumping spring-heeled high in the air, legs a yellow haze as they trampled and hacked with spurs, beaks clattering.

The sergeant's bird was instantly in trouble. I saw a small fountain of blood bubble and spurt out of its neck, and it reeled like a comedian toppling off stilts. The silver cock rallied gallantly and they collided in mid-air, a gunpowder puff of plumes. The crowd was giving a sustained roar, a rhyrnical, grunting Recce, heeee.' Sitting next to me was an elderly Frenchman in a panama hat and a celluloid collar; he had a yellow flower in Lis buttonhole and his hands were clenched tight as roots over the knob of a cane. He pounded the cane on the boards and wheezed 'Reece, heeeee,' as the cocks' necks became first raw, then minced. then only ribbons of red sinews.

Suddenly the speckled cock cracked. It broke free and sped for the wall; but the other did not follow, for it was blinded and was busy twirling gropingly in a circle, its beak lunging mechani- cally at ncthing. Three times the speckled cock flapped up to the rim and three times it was bundled back, and, wh:le the spectators screamed their jeers at it, set beak to beak with the silver cock. The third time it again tried to flee, but the silver cock locked beaks and threw it down, and, flailing ruined wings, it mounted into the air and came down skewering a spur through the speckled cock's neck and into its brain.

There was a great ovation for the brave bird. Its owner pocketed his winnings and then picked it up, and, licking the blood from its eyes and sucking at its wounds, carried it tenderly away. The girl began to circulate with her Turkish delight; more cock-owners jumped into the pit to argue and shout for a fight; I descended the steps and went out into the dust and blinding white heat.

Cockfighting is an ancient and astonishingly persistent sport which spread from China, India and Persia to Greece, Rome and all of Europe and the Americas. In most countries it is now outlawed but by no means defunct (only four years ago thirty-six men and women, including gentleman farmers, cattle-breeders, a church- warden, a racehorse owner and varied county types, were fined for belonging to a Cheshire cockfighting ring, and it is a thriving under- ground sport in Ireland). Haiti is one of the few countries where it is legal, and there it is second only to football in popularity. It is a highly specialised and stylised art-sport, but steel spurs hollow, curved razors slotted and strapped over the natural spurs—are not permitted as they are in Cuba. In Haiti the best birds are held to be those bred in the Dominican. Republic and there is a brisk import-export trade between peasants on either side of the mountain border. A young untrained bird sells for about fifteen dollars—a sizeable investment for a coffee planta- tion labourer or a sugar-cane cutter in a country as ramshackle po-n- as J-laiti (lowest standard of living and per capita income not only in the Caribbean but the whole of Latin America). He hopes that this initial outlay will be won back many times in prize money, and if he has been both lucky and judicious in his choice of game- cock, and has coached and fed it well, he will. His opportunities of putting it to fight are not confined to these vs orking-clats cockpits (equiva- lent, say, to an English industrial town's dog- track), for, if he builds a reputation as a breeder of champions or the owner of a particularly spirited killer, he may succeed in breaking into the hotel circuit.

Cockfighting is part of the exotic tropicana Haiti offers to American tourists. and is adver- tised in the newspapers and brochures in the list of night-life attractions, along with poolside bar-b-q's, creole bullets, meringue bands, roulette and voodou cabaret. This is where the betting is heavy and the pickings from the peckings are good.

• The preparation for such glory and rewards is long, exacting and costly as dedicated a business as training a falcon for the field or an athlete for the Olympics. The cock is kept in his backyard pen behind the peasant's mud-and-thatch caille for perhaps a year before it is ready to fight. It is handled and fondled daily to induce the curious intimate relationship between man and bird. Before tucking it up in its basket each evening, the owner licks its eyelids and head to caress it into a state of steer). During the day its speed of movement and testa aggression are heightened by putting it through enforced runs and sparring matches with other birds As the time for its first main approaches, it is fined down to a hard wiriness—its food (better up to now than the owner's children pet) is reduced to a spare diet similar to a boxer's slabs of underdone steak, and each night it is put in a basket covered with straw and placed mar a fire to sweat off fat. By now it should be about 7 lb of sinewy muscle with legs as lithe as metal springs During the few days before the fight it is tuned up with engorgings of eprzurian fodder—chopped eggs, raw meat, jellies, mixed herbs and butter, and pegs of rum. Puissant with bottled-up virility, a steaming pressure-cooker of aggression. and now delirious with the richness in its stomach and blood, it is ripe lc be stabbed to death within seconds, or, if it has been deserving of the pam- pering and discipline. to inflict the mortal blow first.

It will never km) v that it has acquired renown, and is discussed and praised at great length around cafe tables, but at least it will continue to feast in cannibalistic finery on the eggs of its own kind and to tipple um cocktails—high living not many chickens enjoy.

Previous page

Previous page