Raymond Carr on

What's wrong with Latin America?

What is wrong with Latin America? The answer rings out loud and clear in the new Penguin Latin American Library. The monopoly capitalism of the United States, like some great continental cancer, gnaws away economic progress and strangles Political freedom.

If the diagnosis is correct, then the cure is axiomatic: a radical operation to destroy the growth. Either ' the destruction of the system at its oppressive centre in the United States itself' or a local socialist revolution, Cuban style, that will cut the tentacles and expropriate the expropriators. The former is the conclusion of the Melvilles; the latter that of Carlos Marighela.

The political and psychological trajectory of Thomas and Marjorie Melville* is revealing. Thomas Melville was a Maryknoll Father working among the Guatemalan peasants; obstructed at every turn by the government in his efforts to improve their miserable lot he was expelled in 1967 for intervention in Guatemalan politics. By 1970 he had married and been to prison for entering a draft induction centre and burning the files of recruits destined for Vietnam. His conclusions are hardly surprising. Men of goodwill must recognise the connection between the Pentagon and the Presidential Palace of Guatemala: we are faced with a single course: to dismantle the blind and selfish military industrial complex of the United States.'

Yankee-bashers can, however, base their case on less boggy ground than their own frustrations. The United States would not allow a communist ' regime in Guatemala and Washington's definition of communism, the Melvilles believe, would embrace any regime that gave land to the peasants by a social revolution. President Nixon clearly does not like President Allende of Chile; but Chile is a big country and a long way away, Guatemala small and near. After all, in 1944 the United States intervened actively in the military overthrow of President Arbenz and his ' communist ' government — and the success of this US-backed exile invasion, in my view, dominated US thinking, at least about small Caribbean countries, until the fiasco of the Bay of Pigs. It is to the abandonment of Arbenz's agrarian reform and the refloating of the local oligarchy on the waves of an anticommunist crusade that the Melvilles attribute all the unrest of subsequent years — just as, they argue, it was the abandonment of agrarian reform that caused all the trouble in Vietnam. 'There is only one solution: revolution '; violent revolution that will feed the land hunger of Indians and poor mestizos.

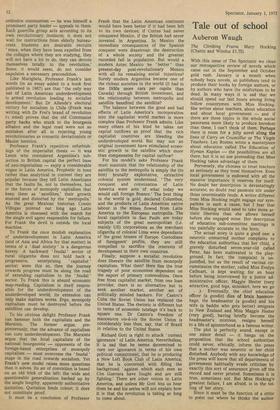

No one can write a convincing defence of Guatemalan regimes since 1944, incapable of reform because reform implies taxation of the rich. But it is a mistake to argue that obnoxious regimes can be overthrown by peasant-based guerrilla movements simply because they are obnoxious and because peasants want land. The Cuban experience was unique; Dr Castro won less because he was supported by peasants than because no sector of society had the guts or inclination to support Batista to the bitter end. Other Latin American countries with reasonably efficient armies — Colombia is a striking example — have lived with sporadic rural violence for a long time. Carlos Marighela, the Brazilian revolutionary leader shot in November 1969, abandoned the pure faith of Debray and Guevara in the efficacy of the rural foco as the slow fuse that would blow up society from the countryside. Its failure was evident when Che Guevara ended dead on a laundry table in the Bolivian backwoods. For Marighela the revolution must start as an urban guerrilla movement, then proceed to mobilise the peasants. Yet it is the peasants who remain the deciding factor in the Brazilian revolution.'

The tactics and strategy of the initial urban movement are set forth in Marighela's collected articles in For the Liberation of Brazil.t Small groups start by expropriating banks, 'a kind of apprenticeship in the technique of revolutionary war.' You capture arms — 'each guerrilla group should have one sub-machine gun . . The ideal sub-machine gun is the .45 INA.' You practice target shooting in amusement parks or at home with an air gun.' Then come the kidnappings (particularly of North Americans), the killings, the catapulting of pieces of glass between the legs of the police horses.' 'An endless series of unforeseeable operations' will wear down the nerves of the government. R. will turn nasty, the people will be on your side and hey presto the revolutionary war is under way. The political situation' will become 'a military situation '; Government troops will shoot the wrong people in error '; political reform will be seen by the masses as a delusion. The IRA please note.

Does it work? Killing the odd ambassador makes the headlines but doesn't make the revolution. Brazilian guerrillas, attacking Marighela's Belo Horizonte-Rio-San Paulo triangle — heartland of industrial Brazil — do not seem to have done much to break the Brazilian boom.

This book — work of a revolutionary martyr — has already become a sacred text to young revolutionaries. His rejection of the dogmatism, caution and discipline of orthodox communism — he was himself a prominent party leader — appeals to them. Each guerrilla group acts according to its own revolutionary instincts; it does not wait for instructions from elderly bureaucrats. Students are desirable recruits since, when they have been expelled from the colleges where they are studying, they will not have a lot to do, they can devote themselves totally to the revolution.' Some, it would seem, do not consider expulsion a necessary precondition.

Like Marighela, Professor Frank's last words (in an essay added to a book first published in 1967) are that the only way out of Latin American underdevelopment is armed revolution leading to socialist development.' But Dr Allende's electoral victory for socialism in Chile (Frank was writing with Dr Frei's brand of revolution mind) proves that the old Communist party hacks who stuck to the bourgeois alliance and the legal road were not so mistaken after all in rejecting young revolutionaries as romantic deviationists or Maoist heretics.

Professor Frank's repetitive refurbishings of the imperialist thesis — it was Lenin who considered Argentina's subjection to British capital the perfect base of neo-imperialism — enjoy a considerable vogue in Latin America. Prophetic in tone rather than analytical in content they are popular because they tell Latin Americans that the faults lie, not in themselves, but in the forces of monopoly capitalism that keep them as 'satellites,' their growth stunted and distorted by the 'metropolis.' As the great Mexican historian Cossio Villegas pointed out long ago Latin America is obsessed with the search for the single evil agent responsible for failure. For Frank the devil is outside the local machine.

To Frank the once modish explanation of underdevelopment in Latin America (and of Asia and Africa for that matter) in terms of a 'dual society' is a dangerous heresy. A backward 'feudal' sector of rural oligarchs does not hold back a progressive, enterprising ' capitalist ' sector; were this so, then the journey towards progress must be along the road of extending capitalism to the ' feudal ' sector. To Frank this is absurd economic map-reading. Capitalism is itself responsible for the underdevelopment of the underdeveloped world; its extension can only make matters worse. Ergo, monopoly capitalism must be destroyed before the satellites can develop.

To his obvious delight Professor Frank can hammer both the capitalists and the Marxists. The former argue, preposterously, that the advance of capitalism can cure underdevelopment. The Marxists argue that the local capitalists of the national bourgeoisie — opponents of the foreign-based enterprises of monopoly capitalism — must overcome the 'feudal' stage in the road towards socialism. Yet Frank's new model raises more questions than it solves. Its air of conviction is based on an old trick of the left: the wide and questionable generalisation backed up by the single lengthy, apparently authoritative quotation. Quotation lends colour; it does not constitute proof.

It must be a conclusion of Professor Frank that the Latin American continent would have been better if it had been left to its own devices; if Cortes had never conquered Mexico, if the British had never invested in Argentina. In Mexico the immediate consequences of the Spanish conquest were disastrous: the destruction of a whole society and the greatest recorded fall in population. But would a modern Aztec Mexico be 'better' than present-day post-revolutionary Mexico with all its remaining social injustices? Surely modern Argentina became one of the richest societies in the world (it had in the 1930s more cars per capita than Canada) through British investment, and the relationship between metropolis and satellite benefited the satellite?

The balance between the good and bad effects of Latin America's incorporation into the capitalist world market is more complex than Professor Frank admits. Like many others of his kind he takes net capital outflows as proof that the rich capitalist countries are bleeding the underdeveloped world. But may not an original investment have stimulated economic growth in the satellite which more than compensates for capital outflow?

For his model's sake Professor Frank must maintain that the relationship of the satellite to the metropolis is simply the (to him) brutally exploitative, extractive colonial system modernised. The very conquest and colonisation of Latin America were acts of what today we would call foreign finance.' The best thing in the world is gold, declared Columbus, and the products of Latin American native Labour in the mines flowed from Latin America to the European metropolis. The local capitalists in Sao Paulo are today subjects of the great metropolitan (i.e. mainly US) corporations as the merchant oligarchs of colonial Lima were dependants of the great houses of Europe. Custodians of foreigners' profits, they are still compelled to sacrifice the interests of development in their own countries.

Finally, suppose a socialist revolution does liberate the satellite from monopoly capitalism. What then? Here lies the true tragedy of poor economies dependent on the export of primary commodities. Once free from capitalist market, from one loan provider, there is no alternative but to seek another market, another set of politically minded bankers. For Castro's Cuba the Soviet Union has replaced the United States. The rhetoric is different but In terms of economic tutelage it's back to square one. Dr Castro's freedom of manoeuvre vis-à-vis the Soviet Union is considerably less than, say, that of Brazil in relation to the United States.

Richard Gott is right to attack current ignorance' of Latin America. Nevertheless, It is sad that he seems determined to cure our ignorance in terms of his own political commitment; that he is producing a New Left Book Club of Latin America; that he is concerned with filling the background 'against which such men as Che Guevara have fought and are still fighting.' There are other voices in Latin America, and unless Mr Gott lets us hear them he and his series will not explain how It is that the revolution is taking so long to come about.

Previous page

Previous page