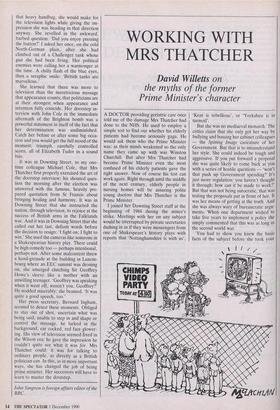

WORKING WITH MRS THATCHER

David Willetts on

the myths of the former Prime Minister's character

A DOCTOR providing geriatric care once told me of the damage Mrs Thatcher had done to the NHS. He used to employ a simple test to find out whether his elderly patients had become seriously gaga. He would ask them who the Prime Minister was: as their minds weakened so the only name they came up with was Winston Churchill. But after Mrs Thatcher had become Prime Minister even the most confused of his elderly patients gave the right answer. Now of course his test can work again. Right through until the middle of the next century, elderly people in nursing homes will be assuring polite young doctors that Mrs Thatcher is the Prime Minister.

I joined her Downing Street staff at the beginning of 1984 during the miner's strike. Meetings with her on any subject would be interrupted by private secretaries dashing in as if they were messengers from one of Shakespeare's history plays with reports that 'Nottinghamshire is with us', `Kent is rebellious', or 'Yorkshire is in turmoil'.

But she was no mediaeval monarch. The critics claim that she only got her way by bullying and bossing her cabinet colleagues — the Spitting Image caricature of her Government. But that is to misunderstand her style. She could indeed be tough and aggressive. If you put forward a proposal she was quite likely to come back at you with a series of hostile questions — 'won't that push up Government spending? It's just more regulation: you haven't thought it through; how can it be made to work?' But that was not being autocratic, that was testing the proposals put in front of her. It was her means of getting at the truth. And she was always wary of bureaucratic argu- ments. When one department wished to take five years to implement a policy she simply commented that this was as long as the second world war.

You had to show you knew the basic facts of the subject before she took your advice. This may seem obvious but it is not the way Whitehall works — senior people provide arguments and juniors provide facts. There was one occasion famous around Whitehall when a senior DTI offi- cial went to advise her on restructuring the steel industry. She asked him how many steel plants we had and where they were. He didn't know. She didn't see why she should accept his advice on. financing the industry if he was so ignorant of the basic facts. If one could reply to her stream of questions in a calm, down-to-earth, factual way, then she was always open to persua- sion and to rational argument.

The great mistake in the view of her as a dictator is that it puts too much weight on her style in handling meetings and ignores the hours she spent working through her papers. Journalists were always too in- terested in who she saw, and not in what she read. That was something the Foreign Office understood very well and the Treas- ury never grasped. The Foreign Office let the tide of paper flow towards her — telegrams would brief her on the Polish harvest. The Treasury, by contrast, always tried to keep its papers away from her and relied on the Chancellor's weekly meeting with her. They would think they had an agreement on the basis of a non-committal comment in one of those meetings when really she had not yet decided. A clear, well-informed minute which she read in the quiet of the flat at two a.m. was much more likely to influence her than weeks of inveigling and arguing at meetings.

Just as it is wrong to picture her as some autocratic bossy-boots, so it is equally mistaken to think of her as so obsessed with free market economics that she would privatise Buckingham Palace if she could. One of the reasons why she doesn't like and doesn't use the term `Thatcherism' is because it makes her view of the world sound like some esoteric personal doctrine picked up from obscure economics text- books. But really she is in the mainstream Conservative tradition of belief in a civil society which can only thrive with limited government. She was never a free market purist. When it came to what she saw as a conflict between free market and patriot- ism, patriotism would always win.

I remember once asking for a Perrier water when she was buying me a snack. She obviously regarded it as treachery to drink a French product and asked why I wanted it. I explained it was because it was naturally fizzy. She replied that the bub- bles were artificially added. We then started arguing about whether the bubbles in Perrier were natural or not. I realised that the situation was becoming absurd and the conversation moved on to matters of high policy. A free marketeer would be horrified at her nationalist instincts, but as always there was a shrewd judgment underlying them. British people are not going to be motivated to be enterprising and accept painful economic changes in pursuit of the vision of a free market, but they may do so if they are told it is because we have to compete with the French and the Germans. Maybe we are like school children who can only be motivated by the desire to be top of the class (or competing with foreigners)., and not by the abstract idea of being well educated (the true equivalent of prosperity).

Anyone who has even worked for her must feel an extraordinary tenderness as well as respect for her. She has many great qualities, but perhaps the one that I value above all is the way that when talking about some dry policy, in public or in private, she could suddenly convey an extraordinary surge of emotion. She could speak about home ownership or the changes in Eastern Europe or improving our schools, and suddenly reach out and hit an emotional note that is quite beyond the reach of most politicians. That is what brought British politics to life.

David Willetts is the Director of Studies at the Centre for Policy Studies, which Mrs Thatcher set up with Lord Joseph in the 1970s.

Previous page

Previous page