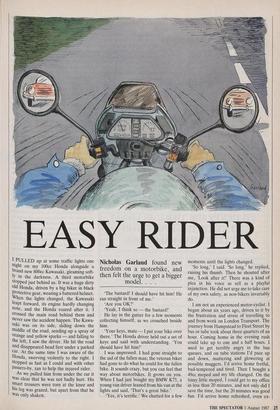

EASY RIDER

Nicholas Garland found new freedom on a motorbike, and then felt the urge to get a bigger model.. . . I PULLED up at some traffic lights one night on my 100cc Honda alongside a brand new 800cc Kawasaki, gleaming soft- ly in the darkness. A third motorbike stopped just behind us. It was a huge dirty old Honda, driven by a big biker in black protective gear, wearing a battered helmet. When the lights changed, the Kawasaki leapt forward, its engine hardly changing note, and the Honda roared after it. I crossed the main road behind them and never saw the accident happen. The Kawa- saki was on its side, sliding down the middle of the road, sending up a spray of orange and yellow sparks — and falling to the left, I saw the driver. He hit the road and disappeared head first under a parked car. At the same time I was aware of the Honda, swerving violently to the right. I stopped as fast as I could and with other passers-by, ran to help the injured rider. As we pulled him from under the car it was clear that he was not badly hurt. His smart trousers were torn at the knee and his leg was grazed, but apart from that he was only shaken. `The bastard! I should have hit him! He ran straight in front of me.'

`Are you OK?'

`Yeah, I think so — the bastard!'

He lay in the gutter for a few moments collecting himself, as we crouched beside him.

`Your keys, mate — I put your bike over there.' The Honda driver held out a set of keys and said with understanding. 'You should have hit him!'

I was impressed. I had gone straight to the aid of the fallen man; the veteran biker had gone to do what he could for the fallen bike. It sounds crazy, but you can feel that way about motorbikes. It grows on you. When I had just bought my BMW K75, a young van driver leaned from his van at the lights and said, 'That's a great bike.'

`Yes, it's terrific.' We chatted for a few moments until the lights changed.

`So long,' I said. 'So long,' he replied, raising his thumb. Then he shouted after me, 'Look after it!' There was a kind of plea in his voice as sell as a playful injunction. He did not urge me to take care of my own safety, as non-bikers invariably do.

I am not an experienced motor-cyclist. I began about six years ago, driven to it by the frustration and stress of travelling to and from work on London Transport. The journey from Hampstead to Fleet Street by bus or tube took about three quarters of an hour. Coming home in the evening rush could take up to one and a half hours. I used to get terribly angry in the bus queues, and on tube stations I'd pace up and down, muttering and glowering at possible muggers. I'd arrive home fretful, bad-tempered and tired. Then I bought a 49cc moped and my life changed. On the tinny little moped, I could get to my office in less than 20 minutes, and not only did I save the time, but the 20 minutes was good fun. I'd arrive home refreshed, even ex- hilarated. Furthermore as soon as I'd acquired the moped, I began to vary my route to take in visits to shops and galleries or friends, detours that would have been impossible by bus. I loved the moped for over a year. But there were problems. Discussing it with a real motorcyclist one day, I learned to my chagrin that he considered a moped to be really a pushbike with an engine attached, whereas even a 100cc Honda is a motorbike.

In fact I could feel the machine was underpowered. Both accelera- tion and braking were sluggish, and the electrics were feeble. The in- dicators didn't work very well and starting the engine soon became a problem.

But the real difficulty was some- thing else. At first all motor bike riders look the same, like anony- mous space riders. Then quite quickly you begin to be able to tell quite a lot about the rider from his machine, his clothes and how he drives. You realise that the reason you develop such strong feelings for a motorbike is that it becomes an extension of yourself. The bike you choose to ride, its colour, its power, its design and cost, as well as how clean you keep it, and which accessories you choose, such as panniers or fairings, form a kind of self portrait. And the fact is I found it increasingly difficult to tolerate being a 49cc moped. Whoever said that no one can look at you with such haughty arrogance as a Masai warrior had never sat on a moped alongside a young man on a Ducatti. Mopeds are cheap, quick and easy to get about on, but I had to have a motorbike.

I bought a 100cc Honda, and at first was terrified even to sit on it in the shop. It seemed vast and heavy. It had gears and a, clutch and a footbrake and a kick-start. I had to ask the salesman how to make it go.

`You get the hang of it in five minutes. They're good fun, these things.'

`For Christ's sake,' a voice inside me argued, 'hundreds of people are killed coming off these things every day.' The salesman suggested that I enrolled for a Star Rider's course. My bike could be delivered to Pimlico Comprehensive School the following Saturday morning where the instruction took place weekly. I i could do a one-day Bronze course in elementary handling and then go on to do the Silver. This is a six-week course in which students are trained firstly in handling the bike, and then in practical road use. You need con- siderable skill to pass the two-part test required for the licence neces- sary to drive anything over 50cc.

My new bike was waiting for me the following Saturday, and there were a number of motorcyclists hanging around. Two were obviously instructors. They had smart gear; they'd polished their boots, wore expensive helmets and took clipboards and papers from their giant panniers. My instructor was Alan, a meticulously formal RAF sergeant who taught Star Riders as a weekend sideline. We began to execute endless figures of eight slowly and evenly round cones that were moved ever closer to each other; then we moved on to elegant slaloms between a series of cones. Event- ually Alan demonstrated a series of man- oeuvres in the school playground, execut- ing the critical right turn which takes place across the line of oncoming traffic. He used indicators, hand signals and glances over his right shoulder. As he turned back again to make the return journey, although he was half hidden behind a low hedge and the demonstration was over, he neverthe- less glanced over his shoulder in the empty playground before changing direction. I was impressed and that lesson has saved my life over and over again. Even when certain there was nothing behind me, I have taken one last look anyway before pulling out, and felt my blood run cold to see a car or lorry almost at my shoulder. Alan called that last look 'the life-saver', and that's what it is.

I was by far the oldest of the group of trainees. Most of them were boys on their first bikes. Alan said the boys had bags of confidence but no skill; the older ones like me were skilful, but had no confidence. When we got out on the road I saw what he meant. Years of changing gears round London gave me an edge on the younger students, to my private relief. Alan taught us 'defensive riding'. 'The purpose is simp- ly to survive each ride.' Boiled right down, what he taught us had a Zen simplicity: always know what you are going to do next, and always let others know before you do it. I found an unexpectedly intense pleasure in driving safely and well. Non- riders might suppose that speed and danger are the real kicks for bikists. I emphatically do not get a kick out of taking risks. Speed is exhilarating, but I am always consciously trying to keep inside a safety margin. The real thrill is more likely to come from a sense of freedom and mobility than from taking risks, which is a sickening and oddly depressing experience. An ex-colleague on the Telegraph told me he'd driven his son's Honda 250 to Portsmouth. 'It was a lovely day. You know as you come off the motorway, you get to the first set of traffic lights before the town — well I was stopped there at the lights, and about eight or ten bikes were soon waiting behind me. When the lights changed we moved off. I was in the lead. The others spread out a little. We were all driving well. You know, not racing; and we swept into town. It was one of the best moments of my life.' He was half laughing at himself, but he meant it.

I began to love hearing biking tales. Later he told me another. 'I was on my big Kawasaki and going into a sharp bend. I knew I had misjudged it. I was going much too fast, too late to brake; I really hung on, heeling over as hard as I dared and just hoped for the best. I was really scared. At the extreme point of the turn, a Ducatti overtook me. I couldn't believe my eyes. As he went by he lifted a hand and waved at me.'

Predictably, within a year I wanted a bigger bike. I found a lot of reasons why: I didn't like the noise of the two-stroke engine, particularly after a friend, frown- ing as I started if, said he'd expected it to go RRRRROAAR! but all it said was baa. Also I was too tall for a small bike and it was not powerful enough. Over any sort of distance it was a strain to drive and with a pillion up it was very unsteady. Actually bigger bikes are safer than small ones, I urged my family. Big tyres grip the road, the weight holds it steady; all bikes can get you into trouble, but the powerful ones can get you out of it faster. Eventually I traded it in for a brilliant red 250cc and at last felt I had a real bike. I really believed I'd never want a bigger machine. But I grew ever more ambitious. I wanted the best; more Power and size and a shaft-driven machine which would mean I didn't have to keep tightening the chain. I agonised about it a bit, and then traded in the 250cc for a K750 BMW — and have never enjoyed a motor- bike more.

I began to ride bikes for practical reasons but by this time know there is a large part of the experience that is to do with something quite other. Becoming part of the sub-culture of the motorcycling world for instance. The messenger boys are not interested in the Zen mastery of the gentleman biker. Like cowboys out on the range, saddlebags flapping, they can be pretty competitive but they are good- natured enough. I like to see the way they gather in growling knots at traffic lights, each carefully noting who is riding what and planning how to be the first to get away, and all pretending not to be looking.

Now and again on a bike you can find your way through a traffic snarl-up and feel like a rugby player who has burst through the defenders and has a clear sprint to the line. I enjoy the amused interest my non-biking friends take in my machine and I enjoy their equally amused envy. I like it when I give someone a ride and they think it is the best fun they've had in years and begin to think they might buy a bike themselves. I really like the versatility, the sense of out-of-one-world and into-the- other. One night we went to the opera, and, parked outside the front entrance, effected a 30-second transformation (my wife in satin culottes under the leggings) before joining the first-night crowd; the next day, in quite a different role, flagged down by a desperate pedestrian I zoomed round to alert the local police of a mugging drama, and had the satisfaction of seeing the villains arrested.

But there is one aspect of racing a motorbike that come as a complete sur- prise to me, and it is in a way the most rewarding part of the whole experience. All motorists have had the experience of driving along a well-known route and suddenly becoming aware that they have been on automatic pilot; they cannot re- member a damn thing about the last ten miles, or recall whether or not they have yet passed a certain landmark. This emphatically does not happen to me on my motorbike. I drive it consciously and with concentration the whole time. It is an activity that simply demands attention. No matter how preoccupied I might be with family or work or financial problems, while I am riding my bike I think about that. Short of knocking myself out with alcohol or some other drug, riding is the best respite I know from a certain kind of anxious fretting. I have often gone for a ride simply to stop my mind churning uselessly over some intractable problem. I know other riders have made a similar discovery — the man riding into Plymouth was talking about the same kind of libera- tion.

This side of biking was expressed by a man who telephoned me in search of material for an article on 'gentlemen bik- ers'. We talked about a new BMW helmet that incorporates a radio system for com- munication with the pillion. He'd tried one out, but found that they were pretty useless over 80 mph. Too much wind and engine noise. 'But they'd be good for tooling around London,' I said.

`Yes, but I'm against them.' He paused. I think he was wondering how I'd take what he was going to say. 'Look, in our society we almost never sit in silence with a companion. We talk or listen to radios or telephone people or play games. Riding on a bike with someone is almost the only time I can think of when you are together, you're communicating, but you don't talk.'

'I see there's a mystic side to biking.'

Then he went to the limit. 'I sometimes think riding a bike is the nearest I get to praying.' And he wasn't kidding.

I wouldn't go that far. But to those who've never tried it, who feel jaded and think that life has no more new excite- ments, I'd say take a Silver Rider's course on a 125cc and then graduate to something a little bigger.. . .

Previous page

Previous page