THE BEST OF FRENEMIES

Simon Heifer believes the differences between Labour and the Tories are much fewer than they pretend

THE PARTY conference season is a ritual of abuse and counter-abuse, accusation and counter-accusation. It was hard, though, to see what all the excitement was about this time. Whatever the rhetoric, both parties seem to be moving towards the centre, where they risk meeting each other. Both are committed to full welfare provision, better public services, strong defence, European integration and running the British economy (to the extent that there is an independent British economy to run) on orders from Brussels or Frankfurt. It seems the closer the two parties become the more their supporters insult each other, as if to build the pretence to the electorate that there really are great differences between Labour and the Tories. It looks, though, like a case of protesting too much.

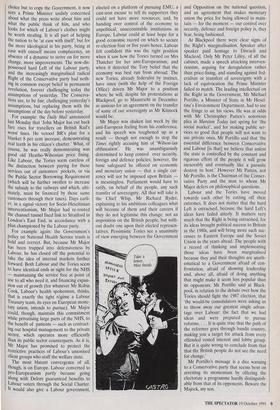

Mr Butskell was an invention of the 1950s, a symbol of the cynical pursuit of the middle way and the avoidance of too much principle — or imagination — by both main parties, a blend of Butler and Gaitskell. Mr Majock risks becoming the equivalent in the 1990s, the merging of Messrs Major and Kinnock as their parties, too, pursue an unadventurous and econom- ically retarding consensus in the hope of not frightening the voters with anything approaching radicalism. In his speech to the Tory conference last week Mr Major may sometimes have sounded like Mrs Thatcher, in his promises to leave the NHS safe in his hands, to further ownership and to have no single European currency 'imposed' upon us. However, the briefings given by his officials afterwards stressed it was really a 'one nation' speech, which is Tory code for the antithesis of Thatcherism; and something very close to what the Labour party, as it has moved to the right, believes in.

At Brighton earlier this month, Mr Kin- nock made no absurd spending commit- ments: indeed, in his determination to be more pro-European than the Tories, he pledged his party to be in 'the first division' (Toryspeak: 'the heart') of Europe, which he knows means running the low budget deficit his future masters in Brussels or Frankfurt tell him is compatible with secur-

ing the goal of monetary union. The Tories do not yet believe in some of Labour's more radical ideas (like a minimum wage, a subject said to have been well aired at Mr Heath's dinner-parties at Blackpool last week) or more power to the unions, but on the big questions of economic management and Europe (which are inextricably linked), the building up of public services and the maintenance of the welfare state, the two parties' thinking is converging nicely.

Take, for example, these sentiments from Mr Kinnock's Brighton address, none of which would now shock most Tories if uttered by the Prime Minister in his 'one nation' guise: 'People look at our society and they look at our neighbours in the rest of the Community. They see the high stan- dards of training, the quality of child care, the investment in public transport, and ask: 'Why not here?' The answer is that it can change. 'We can do it here.' Commenting on Labour's new commitment to defend Britain, one of Mr Kinnock's associates

told the Times: 'A Labour government will spend what is needed to ensure the nation's proper defence and will not be swayed by some arbitrary formula,' which, given what hard-line Tory MPs were saying in the Commons' defence debate earlier this week about the Tories cutting too much out of the army, puts Labour to the right of the Government on this issue. Labouralso has its own citizen's charter, and plans to decentralise power. The Tories want to decentralise too, and like Labour persist in the nonsensical idea that this can only be done by large-scale inter- vention. As Mr Michael HeseItine said in his speech to the Conservative Party Con- ference: 'If we intervene, we are accused of centralism. But if we want to decentralise power to the people, we have to make it happen.'

Mr Heseltine also signalled the new Tory philosophy of non-confrontationalism: 'Let's be frank. There are no solutions which carry universal support ... Our poli- cies must command consent across the country as a whole.' It was precisely because Labour realised its policies 'must command consent across the country as a whole' that it engaged in the most spectac- tular act of revisionism in British politics since Mr Heath's U-turn in 1972. It was dragged rightwards by a Conservative gov- ernment whose radical policies were deemed a success by the public. So Labour embraced markets; it watered down (and has just about abandoned) plans for re- nationalisation; noting the wishes of the electorate, it became enthusiastic about the right to buy council houses and about a national curriculum in schools. While not • promising to cut taxes (something the Tories, with a budget deficit of £20 billions by next spring, will be in no position to do either), it pledges to raise them only for the so-called 'rich'; but then making sure the rich pay more is an underlying principle of Mr Heseltine's council tax too.

Now the Conservative party is moving back towards the centre, pulled by what it — ironically — sees as the success of Labour's new, fashionable position there. Whereas Labour once seemed to have no choice but to copy the Government, it now sees a Prime Minister unduly concerned about what the press write about him and what the public think of him, and who looks for which of Labour's clothes might be worth stealing. It is all part of helping the nation to be 'at ease with itself; but for the more ideological in his party, being at ease with oneself means complacency, an absence of a dynamic to strive on for more Change, more improvements. The now-dis- possessed hard Left of the Labour party, and the increasingly marginalised radical Right of the Conservative party had noth- ing in common except belief in permanent revolution, forever challenging today the assumptions of yesterday. The Conserva- tives are, to be fair, challenging yesterday's assumptions, but replacing them with the assumptions of the day before yesterday.

For example: the Daily Mail announced last Monday that 'John Major has cut back fare rises for travellers on British Rail's worst lines. He vetoed BR's plan for a blanket 8 per cent increase, demonstrating real teeth in his citizen's charter.' What, of course, he was really demonstrating was good old Heatho-Wilsonian price fixing. Like Labour, the Tories seem careless of the distinction between paying for these services out of customers' pockets, or via the Public Sector Borrowing Requirement (which will be further swollen to increase the subsidy to the railways and which, ulti- mately, must be financed by those same customers through their taxes). Days earli- er, in a signal victory for Socio-Heseltinian interventionism, Mr Major had re-routed the channel tunnel fixed link to Stratford in London's East End, in accordance with a Plan championed by the Labour party.

For example again: the Government's Policy on National Health Service trusts is bold and correct. But, because Mr Major has been trapped into defensiveness by Labour, he has closed off the potential to take the idea of internal markets further forward. Both Labour and the Tories seem to have identical ends in sight for the NHS — maintaining the service free at point of LiSe to all who need it, and financing expan- sion out of growth (for whatever Mr Robin Cook, Labour's health spokesman, thinks, that is exactly the tight regime a Labour Treasury team, its eyes on European mone- tary union, intends to pursue). Mr Major could, though, maintain this commitment While privatising large parts of the NHS, to the benefit of patients — such as contract- ing out hospital management to the private sector, which operates more efficiently than its public sector counterparts. As it is, Mr Major has promised to protect the restrictive practices of Labour's unionised client groups who staff the welfare state.

The most blatant convergence of all, though, is on Europe. Labour converted to pro-Europeanism partly because going along with Delors guaranteed benefits to Labour voters through the Social Charter. It would also give a Labour government, elected on a platform of pursuing EMU, a cast-iron excuse to tell its supporters they could not have more resources; and, by handing over control of the economy to unpolitical, unaccountable institutions in Europe, Labour could at least hope for a good economic record on which to secure re-election four or five years hence. Labour felt confident this was the right position when it saw how the Tories turned on Mrs Thatcher for her anti-Europeanism, and when it detected the Tory belief that the economy was best run from abroad. The new Tories, already federalist by instinct, have since (with the help of the Foreign Office) driven Mr Major to a position where he will, despite his protestations at Blackpool, go to Maastricht in December as anxious for an agreement on the transfer of some of our sovereignty as Mr Kinnock would be.

Mr Major was shaken last week by the anti-European feeling from his conference, and his speech was toughened up as a result — though not enough to stop the Times rightly accusing him of 'Wilson-ian obfuscation'. He was unambiguously determined to keep control over security, foreign and defence policies; however, the basic safeguard he offered on economic and monetary union — that a single cur- rency will not be imposed upon Britain — is meaningless. Parliament would have to ratify, on behalf of the people, any such transfer of sovereignty. All that will take is the Chief Whip, Mr Richard Ryder, explaining to his ambitious colleagues what will become of them and their careers if they do not legitimise this change: not an imposition on the British people, but with- out doubt one upon their elected represen- tatives. Pessimistic Tories see a unanimity of view emerging between the Government and Opposition on the national question, and an agreement that makes monetary union the price for being allowed to main- tain — for the moment — our control over security, defence and foreign policy is, they fear, being fashioned.

At Blackpool there were clear signs of the Right's marginalisation. Speaker after speaker paid homage to Disraeli and Macleod. Only Mr Peter Lilley, of all the cabinet, made a speech attacking interven- tionism, arguing for deregulation rather than price-fixing, and standing against fed- eralism or transfers of sovereignty with a lack of equivocation the Prime Minister failed to match. The leading intellectual on the Right in the Government, Mr Michael Portillo, a Minister of State in Mr Hesel- tine's Environment Department, had to use the fringe to air his views. He was at odds with Mr Christopher Patten's notorious plea in Marxism Today last spring for 'the social market', and for making public ser- vices so good that people will not want to use private ones. Mr Portillo said that 'the essential difference between Conservative and Labour is that] we believe that unless the state is controlled by the constant and rigorous effort of the people it will grow inexorably and eventually like a parasite destroy its host.' However Mr Patten, not Mr Portillo, is the Chairman of the Conser- vative Party and the man to whom Mr Major defers on philosophical questions.

Labour and the Tories have moved towards each other by cutting off their extremes. It does not matter that the hard Left is ostracised, because the hard Left's ideas have failed utterly. It matters very much that the Right is being ostracised, for its ideas brought political success to Britain in the 1980s, and will bring more such suc- cesses to Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union in the years ahead. The people with a record of thinking and implementing those ideas have been marginalised because they and their thoughts are anath- ematical to a Government afraid of con- frontation, afraid of showing leadership and, above all, afraid of doing anything that might make it seem less popular than its opponents. Mr Portillo said at Black- pool, in relation to the debate over how the Tories should fight the 1987 election, that 'the would-be consolidators were asking us to throw away our greatest single advan- tage over Labour: the fact that we had ideas and were prepared to pursue reforms.. .. It is quite true that the path of the reformer goes through bandit country, making you a target for attack from every offended vested interest and lobby group. But it is quite wrong to conclude from that that the British people do not see the need for change.'

Mr Portillo's message is a dire warning to a Conservative party that seems bent on arresting its momentum by offering the electorate a programme hardly distinguish- able from that of its opponents. Beware the Majock, my son.

Previous page

Previous page