The white rabbit of the arts

Kay Dick

Another Part of the Wood Kenneth Clark (John Murray £4.75) I have nearly been seduced — by Kenneth. Which means that I have been reading with concentrated and fascinated interest Sir Kenneth Clark's first chapter of autobiography, Another Part of the Wood, to be continued in succeeding serials. I can now fully appreciate how this charmingly informed art-man seduced a whole nation with his television performances. Not enjoying the dubious benefits of owning a television, I had previously not wholly understood how Sir Kenneth persuaded so many semi-literates that art could be thrilling, although I had read several of his books. It is a mystery no longer: metaphorically, 1 too have sucked the 'lollipop. Ruskin, Sir Kenneth's hero (one of them) similarly swayed a more literate Victorian audience, rather more suavely perhaps than did Carlyle in his lectures as he browbeat high-society.

With his usual exquisite grace Sir Kenneth unfolds the first thirty-five years of his life; youthful years all of them: one has a great sense of viewing a perpetual jeunesse doree in these adventures of a very handsome and elegant person. Certainly Sir Kenneth has sex appeal; no television fan would deny this, apart from some irate husbands who do not hold with arty-chaps. Sir Kenneth's teenage photograph is that ideal boy-next-door with whom one hoped to dance, to play tennis, and gosh, talk about art and beauty. He is so scrupulously open, at least so it seems, as he lets us into glimpses of that outrageously privileged Edwardian family background. Father's money came from trade, but not to worry, he lived like a lord, even better, giving endless houseparties, shooting lots of little birds (Kenneth junior was appropriately sensitive about this), yachting (this showed Kenneth that Turner's seascapes were right), and actually broke the bank at Monte Carlo several times which, as Sir Kenneth says, is easy enough if you have enough money to chuck away. It is admirable, really so, that Sir Kenneth twisted himself out of that philistinian haute bourgeoisie, although it came in handy later (he was never to be impressed by mere wealth), and turned his life to art. He records his first artistic influences: Japanese prints, Beardsley, Turner, Cezanne. "At the age of nine I said with perfect confidence, 'This is a good picture, that is a bad one.'' He learnt early to be authoritative. Let none think I have failed to enjoy every page of these reminiscences, even though I did expect to find that the proportion of cultivated gossip-column anecdotes would perhaps be shored up more firmly with some deeper speculation and comment. After all, Sir Kenneth had Ruskin's Praeterita as a model to hand. Not that Sir Kenneth is beastly mean: he does offer some personal touches. He is happy to record that he is "a confirmed heterosexual" and has ever received "a remarkable sympathy" from "those of other persuasions." In his teens he suffered, at times, from "accidie, maladie des moines"; he properly expresses disgust at the gorging which takes place at public dinners; admits he's a cold character; endearingly states, "I am by nature exceedingly mean," and that during his courtship all he bought his girl was a paper-bag of peppermint bulls-eyes. Early he acknowledged his limita tions. He was not good enough to shine as an original painter, so he took to art history instead, helped by an exceptional stroke of social luck in getting himself attached to Bernard Berenson's court as an oddjobman (this section is pure delight — just the right touch of malice).

Appointed to catalogue the Leonardos at Windsor Castle made a great difference to Sir Kenneth's career; it helped him to write his first book and to his appointment as Director of the National Gallery at thirty (that jeunesse doree again!). He grew up rapidly: "When I married I was thoughtless, unimaginative and completely self-centred." The birth of a first son made a difference: "I had to think, of other people." Oddly enough one has a feeling that Sir Kenneth was born 'grown-up' in the common parlance of the classification.

Lovely bits of travel notes, as expected from one with a feeling for landscape, and smashing gossip, dinner-party vintage, topped by some intimations about those "famous" National Gallery squabbles, all such contribute to the smile on the face of the reader. Sir Kenneth placed himself beyond intrigue. "What, in this welter of worldliness, grandeur and official business, had happened to the scholar-aesthete whom I have tried to rediscover?" Well, Sir Kenneth knew his rich and his patrons, and thoroughly understood the inner workings of their minions, civil servants and politicians, so he quietly built up his own collection of works of art, "making far more lasting and rewarding friendships with artists." Finally, as one expects the sentiments of a cultured man, a Renaissance-inspired man, to be, Sir Kenneth, without hesitation, places his finger on the pulse, dead-on spot: "The artist must go at his own speed. His whole life is a painful effort to turn himself,inside out, and if he gives too much away at the shallow level of social intercourse he may lose the will to attempt a deeper excavation."

Why, might the reader wonder, in view of all my distinct enjoyment of Another Part of the Wood, am I ultimately reluctant to say yes to Sir Kenneth's seductive siren-song? Best perhaps to explain this by quoting Sir Kenneth's own admission that "I am the original White Rabbit." Possibly Sir Kenneth failed to glance again at his Wonderland before making such a confession. I did, and confirmed that The White Rabbit wore beautiful gloves and carried a fan, which articles when handled by Alice turned out not to be what they seemed. I noted, yet again, that White Rabbit had social aspirations, bowed to all Duchesses, enjoyed giving commands to the lower orders, and was distinctly uneasy: "Oh dear, I shall be too late." That White Rabbit's door plate was bright and brassy, and that, once, in dismay, when contradicted by Alice, he fell onto a cucumber-frame, and broke it, and that whenever at a loss he exclaimed, "Burn the house down." White Rabbit was also a bit of a sneak, yet got himself promoted to Herald, and advised the King about criminal procedure; that he eventually tricked Alice, whom he called as a witness, offered false evidence against her, and was finally responsible for her sentence "Off with her head." Could Alice in Sir Kenneth's identification with White Rabbit be art? Somewhere in all this are my reasons for remaining unseduced by Sir Kenneth.

Kay Dick has most recently written Friends and Friendship.

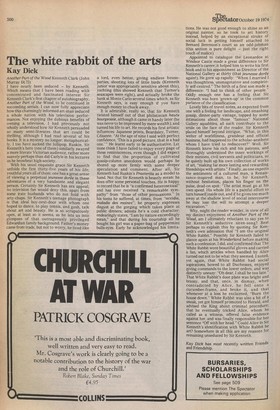

Previous page

Previous page