Economists and the Common Market

By NICHOLAS DAVENPORT

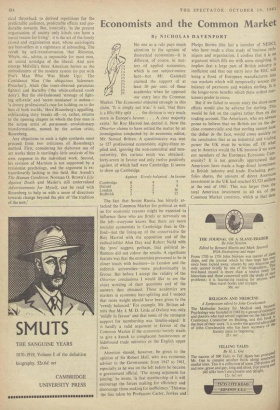

No one as a rule pays much attention to the opinion of theoretical economists—it is different, of course, in mat- ters of applied economics, which is our subject-matter here—but Mr. Gaitskell claimed the support of at least 50 per cent. of these academics when he opposed our entry into the Common Market. The Economist objected strongly to this claim. `It is simply not true,' it said, `that there is a fifty-fifty split . . . the division is very much more in Europe's favour. . . . A clear majority exists.' Sir Roy Harrod has denied it. Now the Observer claims to have settled the matter by an investigation conducted by its economic editor, Mr. Samuel Brittan. A questionnaire was sent to 127 professional economists; eighty-three re- plied and, ignoring the non-committal and non- university, this curious result was obtained: forty-seven in favour and only twelve positively against, of which half were Cambridge. It seems to show up Cambridge.

Against Evenly balanced In favour Cambridge 6 4

7

Oxford 2 5

9

London 2 2

16

Redbrick 2 7

15 The fact that Soviet Russia has bitterly at-

tacked the Common Market for political as well as for economic reasons might be expected to influence those who are firmly or nervously on the left—everyone knows that there are more socialist economists in Cambridge than in Ox- ford—but the lining-up of the conservative Sir Roy Harrod with the opposition and of the radical-leftist Alan Day and Robert Neild with the `pros' suggest, perhaps, that political in- fluences did not colour the results. A significant feature was that the economists presumed to be in closer touch with business—in London and the redbrick universities—were predominantly in favour. But before 1 accept the validity of the Observer conclusions I would like to see the exact wording of their questions and of the answers they obtained. These academics are masters in economic hair-splitting and I suspect that more weight should have been given to the `evenly balanced.' For example, Mr. Brittan ad- mits that Mr. I. M. D. Little of Oxford was only `mildly in favour' and that some of the strongest support for membership was `double-edged.' It is hardly a valid argument in favour of the Common Market if the economist merely wants to give a knock to complacent businessmen or hidebound trade unionists or the English upper class.

Attention should, however, be given to the opinion of Sir Robert Hall, who was economic adviser to the Government from 1947 to 1961, especially as he was on the left before he became a government official. `The strong argument for joining,' he wrote, `is that membership of it will encourage the forces making for efficiency and discourage those making for inefficiency.' This was the line taken by Professors Carter, Jewkes and

Phelps Brown (the last a member of NEDC), who have made a close study of business tech- niques and organisation. I confess that it is an argument which fills me with some misgiving. It implies that a large part of British industry is inefficient and that our entry into the EEC will bring a flood of European manufactures into our markets which will temporarily worsen the balance of payments and weaken sterling. It 15 the longer-term benefits which these ardent mar- keteers prefer to stress.

But if we failed to secure entry the short-terrn effects would also be adverse for sterling. This would be felt on the capital rather than on the trading account. The Americans, who are always prone to believe that we British are on the de- cline commercially and that sterling cannot look the dollar in the face, would come quickly to the conclusion that as an industrial and trading power the UK must be written off. Of what use to America would the UK become if we were not members of the European Economic Com- munity? It is not generally appreciated that Americans have made a huge direct investment in British industry and trade. Excluding port- folio shares, the amount of direct American investment in the UK had reached $3,523 million at the end of 1961. This was larger than the total American investment in all six of the Common Market countries, which at that date

THE SPECTATOR, OCTOBER 19 was only about $3,000 million. The first thing the Americans would do, if the Brussels nego- tiations broke down, would be to liquidate their Portfolio investments in the UK and then to start Pulling out of their industrial and trading in- vestments. The £ could not be expected to stand up to such a flight of capital for very long.

It seems to me that economically we are trapped. If we stay out we can look forward (1) to a fairly sharp fall in our exports to the EEC and (ii) to a further decline in the exports of our manufactures to the Commonwealth as these countries increase the protection of their Own developing industries and we are forced eventually to limit the buying of their foodstuffs by quotas. If we go in, we must expect- an immediate knock in our home markets while European manufactures. flow in and a rise in the cost of our imported food, which is most objec- tionable. Unless the promised world commodity agreements are written on very liberal terms, the world outside, as Sir Roy Harrod says, may be temporarily worse off. We must hope that in the long run our exporting industries will become more efficient and our farmers more prosperous (without subsidies) and that the rise in food Prices will be offset by a cut in purchase taxes. But let us make no mistake about the penalties of staying out. We can expect no help from America, and the benefits of the reciprocal lowering of tariffs which Mr. Kennedy is expect- ing to negotiate with the EEC on common manu- factures will hardly be extended to a Britain who is not a member of the European club. If we are not blackballed. we could be black- mailed.

So, whatever the economists say, it is my belief that the new Britain will be carried along on the stream of history into the new Europe. It will be uncomfortable and unpleasant for a lot of us (especially for the aged and poor), but it Is too late now to start swimming against the current. Fourteen months ago I pointed to the tragedy awaiting New Zealand unless very special terms were secured for her and I sug- gested that we should offer them union. They were too proud even to discuss the problem. But it is now obvious that if the old Common- Wealth is to be preserved some new relationship think will have to be devised immediately. Failure to quickly and to see clearly ahead means that our pale white Prime Ministers could have attended their last Commonwealth Con- ference.

Previous page

Previous page