More Power for the Car Driver

BY OLIVER STEWART POWER and the almost limitless secondary ways of using it in a motor-car are the chief attractions at Earls Court. The driver of a 1957 model has more power in his engine and more power at his elbow. He is asked only to tilt a toe or lift a finger and the stuff pours from the engine: hydraulic pumps and rams, vacuum servos, electric motors and negative feed-back systems jump into action and work the clutch, change the gears, boost the steering and the braking and raise and • lower windows and heads.

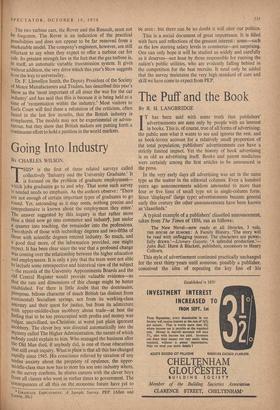

The extended automaticity which is the mark of the new cars, branches from increased engine output, and that has been obtained chiefly from higher compression ratios. From the Morris Minor to the Bentley they are all up : the Minor from 7.2 tol to 8.3 to 1; the Bentley from 7.25 (for the Continental) to 8 to 1. The new Rover goes to 8.5 to 1. Higher compression ratio gives more power, but not at the expense of higher specific fuel consumption. The price it exacts is usually heavier crank- shafts and big-end bearings and fuel of high octane rating.

There is plenty for the extra power to do; but Citroen remains the only maker in the world to see the fully powered motor- car and to see it whole. As in Paris last year, so at Earls Court this year, the DS 19 stands out as an integrated power system. An engine-driven hydraulic pump boosts the steering and the braking (discs in front) and ministers to gear-changing and sus- pension. British and American car makers are, as yet, content to add a bit of automaticity here and a bit there. Of these bits assisted steering is the most interesting.

It is found in the Rolls-Royce and in the Armstrong Siddeley Sapphire. The Sapphire has an over-riding manual control so that the amount of power can be varied. During a week's trial of the Sapphire I succumbed to the fascination of power steer- ing. On the open road it makes little difference; but when manoeuvring in traffic or in a garage or a parking place, the ability to spin the steering wheel with a finger is an appreciable pleasure.

An objection sometimes raised is that powered steering deprives the driver of 'feel.' It is by the feel of the steering wheel that the tyre adhesion on varying road surfaces is directly signalled to the driver. With full power, the Sapphire wanted watching on a fast but winding road. In the Rolls-Royce, which I shall not be able to try until after the Show, it is claimed that feel is present as in manual steering. The power application is adjusted so that it does not begin until a certain load has been applied to the wheel. In addition to this form of feel there is the form that varies with speed; '0-feel,' as air pilots call it (and power controls in aircraft have points of resemblance to power controls in motor-cars). Again Rolls-Royce say that they have found the solution to the adjustment of feel with speed.

Automatic transmission systems are legion. They are mostly of 'American origin even though they may be built here. Of British origin are the Hobbs (seen last year in the Lanchester Sprite) and the new Rover transmission which uses a torque converter. It is in the 105 R. Fully automatic transmissions are still too heavy, too complicated and too expensive for the smaller cars, and we see this year a number of 'two-pedal' systems in which the gears are still changed by hand, but the clutch operation and the adjustment of engine speed are auto- matic. There is also the Laycock de Normanville overdrive which, for the driver, has some of the characteristics of an auto- matic transmission.

British makers still shine in sports cars. We must all regret the withdrawal of Jaguar from racing; but this make has borne a heavy burden and its successes at Le Mans and elsewhere have helped British sports cars in general. Few have any right to quarrel with the decision taken by Sir William Lyons. During the past season Aston Martin cars have been responsible for maintaining the British reputation for building high-perform- ance sports cars. The pioneer work done by these machines on disc brakes is alone justification for the time and money lavished upon them. The Triumph TR3 is the first British car in large-scale production to fit disc brakes as standard.

If a quick survey is now made of a few detail design features. a less satisfactory situation is discovered. It is astonishing that expensive cars should still demand that, in order to check the engine sump oil level (instruction books say it should be done daily), the driver must open the bonnet and plunge an arm into the murky recesses alongside the engine. It is astonishing that there should be no radiator water-level indicators; that the topping-up of batteries should be left to intermittent inspec- tion and fiddling with distilled water bottles when a simple. semi-automatic sight feed could be fitted.

Tyre makers insist that they can now supply tyres with tube- less covers and secondary inner air chambers which will always get the motorist home. But there is still the utmost hesitancy among car makers to throw away the spare wheel and the built- in jacking system. The saving in weight would be appreciable; there would be more room for luggage and prices could be slightly reduced.

As one who owns a continental make of car, I express a personal preference when I say that I would not willingly own a car with the low-geared steering found in many British and most American cars; or a car without independent suspension on all four wheels; or a car with the doors opening in the 'wrong' direction, that is, hung at the rear. I am also sensitive to the inadequate handbrakes which, if applied really hard to hold the car on a steep incline, can only be released after an exhaust- ing struggle. I was glad to notice the Bentley Continental with a handbrake whose ratchet is freed by twisting the handle.

Air-cooled engines have their enthusiasts, but they also have vigorous opponents. It is a pity that such an interesting car as the Dyna Panhard is difficult to acquire in England. It is also a pity that this pioneer French maker should have weakened and should, this year, have modified the brilliant original design of this twin-cylinder, air-cooled, front-drive car by substituting steel for the light alloys originally specified for the body. The two turbine cars, the Rover and the Renault, must not be. forgotten. The Rover is an indication of the practical Possibilities and does not appear to be far removed from a marketable model. The company's engineers, however, are still reluctant to say when they expect to offer a turbine car for sale. Its greatest strength lies in the fact that the gas turbine is. in itself, an automatic variable transmission system. It gives without addition, the very drive which this year's Show suggests is on the 'way to universality.

Dr. F. Llewellyn Smith, the Deputy President of the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders, has described this year's Show as the 'most important of all since the war for the car industry' and has said that this is because it is being held at a time of 'reorientation within the industry.' Most visitors to Earls Court will find there a refutation of the criticism, often heard in the last few months, that the British industry is complacent. The models may not be experimental or adven- turous; but they show that British makers are putting forth a continuous effort to hold a position in the world markets.

Previous page

Previous page