Goodbye to Jack Jones

Patrick Cosgrave

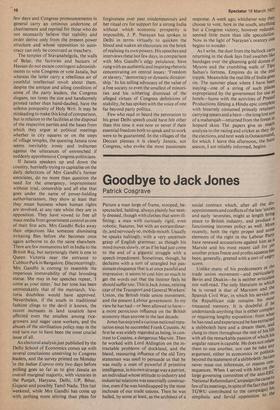

Picture a man large of frame, stooped, bespectacled, balding, always plainly but neatly dressed, though with clothes that seem illfitting; a man with curiously rigid, even robotic, features, but with an extraordinarily, and nervously so, mobile mouth. Usually he speaks haltingly, with a very uncertain grasp of English grammar, as though his mind moves slowly, or as if he had just come to the end of a gigantic struggle with a speech impediment. Sometimes, though, he declaims with a sort of strangled but passionate eloquence that is at once painful and impressive: it seems to cost him so much to get the words out that the listener feels he should suffer too. This is Jack Jones, retiring czar of the Transport and General Workers' Union, the British trade union movement, and the present Labour government. In my View he has had—or been allowed to have— a more pernicious influence on the British economy than anyone in the last decade.

Jones has enjoyed a curious national reputation since he succeeded Frank Cousins. At first he was widely regarded as being, in contrast to Cousins, a dangerous Marxist. Then he worked with Lord Aldington on the intractable problems of dockland, and the bland, reassuring influence of the old Tory statesman was used to persuade us that he was really a man of powerful if primitive intelligence, in his own strange way a patriot, an individual whose attitude to industry and -industrial relations was essentially constructive, even if he was handicapped by the most inchoate of our trade unions. Then he was hailed, by some at least, as the architect of a social contract which, after all the dis" appoint ments and conflicts of the late 'sixties and early 'seventies, might at length bring peace to British industry, and produce a functioning incomes policy as well. More recently, both the right proper and sonic elements of the right in the Labour PartY have renewed accusations against him as 3 Marxist and his most recent call for Yet another prices freeze and profits squeeze has been, generally, greeted with a sort of angrY scorn. Unlike many of his predecessors in the trade union movement—and particularlY Bevin and Deakin—he is neither articulate nor well-read. The only literature in which

i

he s versed is that of Marxism and the Spanish Civil War, in which his Service on the Republican side remains his most treasured memory. It is doubtful if he understands anything that is either comPle74 or requiring lengthy exposition: from what, he has read and experienced he has extractea, a shibboleth here and a dream there, an° clung to them throughout the rest of his hf.e with all the remarkable passion of which his angular nature is capable. He does not relate them to one another, nor can he take. argument, either in economics or politic5,. beyond the statement of a shibboleth : he can never tease out inferences, or reason consequences. When I served with him on large governing committee of the antiNational Referendum Campaign (he came t° few of its meetings, in spite of the fact that the TGWU contributed to the campaign) Ills simplistic and fervid opposition to the Market was evident; his failure to grasp the details of arguments often embarrassing. He Is incapable of any kind of intellectual consistency or, indeed, of prolonged thought. And when that incapacity is sensed by him he can be both pathetic and threatening as When, at the Labour Party conference of 1975, during an exceptionally well-reasoned, Quietly expressed, and impeccably Socialist critique of economic policy by fan Mikardo he rushed a Tribune platform and shoved the sPeaker aside, himself to declaim, not against any unorthodoxy, but against the fact that Mlkardo disagreed with him. Atsuch moments Jones offers unpleasant reminders of what life can be like for those who dissent from the judgments of tough shop stewards on factory floors. Of his authorship of the social contract there can be little doubt. He first put the concept forward at a Fabian tea party during the Labour conference of 1971. When, subsequently, there was much dispute (of a kind the Labour movement loves) over whether it was a 'compact' or a 'contract', or whether it existed at all, he said : 'I am quite willing to settle for the word "contract" instead of compact" because that is what it means—a unique agreement between the two wings of the Labour movement.' Fair enough—if that is what it was. But he added, in 1974: The idea is to try and encourage a climate Where because of social improvements like Increased pensions, controlled prices, and redistribution of wealth so that more people can get their fair share, we shall also improve °Lir industrial relations.' That is how it has always been—a long list of things which the Other side must deliver, but only the vaguest expression of an aspiration from Jones. • Always and again Jones states the emo11chal—not always the practical—requirenlehts of the trade union movement or, rather the trade union movement as he visualises it, and as it may once have been, not as it really is now. He is clearly puzzled and hurt by increasing discontent among the rank and file with his economic policy: after all, has he not told them again and again that wage restraint is a worthwhile price to the to keep unemployment down and secure 'he legislative enactment of his other dreams --frozen prices, wider nationalisation, the Protection for ever of employment opportunities for his own dockers? Why do they hesitate before building the New Jerusalem owf!tAh him ? Has he not called for the abolition ri'd's times? as an affront to trade unionists in Imes? Did he not enlist in the Spanish C., War solely, as he put it himself, because e Franco rising was 'an attempt to crush the unions'? Why, then, do they not see things his way? The remark about the :attire of the Spanish Civil War—in an irticle in the Observer last year—is typical of °.hes's disproportionate view of life. Certainly, Franco wanted to bash the unions; out the war was about much more than that. The damage Jones has done is to be seen

that in a repeatedly expressed belief

k :at an economic situation—even the whole c°h°mY—can simply be frozen if he doesn't

like the way it is developing. The Dock Labour Regulation Act has been the most spectacular manifestation of his will in this regard. But throughout his history as a union leader the emphasis has been the same. A speech in December 1973, for example, is uncannily reminiscent of the address the other day in which he called for a price freeze. Then he wanted the same package: freezing of rents, prices and mortgages, higher pensions, reversals of tax concessions to the middle classes, and subsidies of all sorts, shapes and varieties.

The more sinster aspect of Jones as an agent of inflation could likewise be seen in

1973. Then he said, 'We are greatly worried that the blame is attached to working people, when the responsibility belongs to the Government itself.' Now, one does not have to be a fully paid up monetarist to accept that government spending has something to do with inflation : but in that speech, as in all his other major pronouncements, Jones has called, at one and the same time, for the acceptance by government of responsibility for inflation and at the same time for measures which would increase government's contribution to the phenomenon. And, since the present Labour government has almost invariably done his bidding, there is not much in his acceptance of recent minimal expenditure cuts and a measure of wage restraint to set against his huge contribution to the Public Sector Spending Deficit.

Simple dullness, however, and antique working-class romanticism, are not sufficient to explain his attachment to the Soviet Union—which country, after all, is not noted for kindness to free trade unions. Yet he described himself as feeling 'at home' there. He has encouraged the lifting of traditional TUC and Labour Party bans on Communist and Communist front organisations. He clearly loves going to Russia; and he entertained — royally — the infamous Shelepin. Surely this defeats any pleas in mitigation of the accusation that he has been a consciously malign influence in British politics?

I do not thing it does. The extraordinary thing about him is not—as some of his Tory admirers even now think—that he has learned something about the facts of economic life from events and Toby Aldington. It is that he has not changed one iota, in character or mental outlook, from the 'thirties. Though many British trade union leaders remain deeply influenced by that period, it would not be true to say of them that they have remained unchanged since. But it is true of Jones: in the 'thirties Russia was good, and Franquist Spain bad. So it remains. So, in his vision, it must remain. Nothing, but nothing, is relevant but that formative period. Like prices, history is to be frozen: he is the perfect type of the old fellowtraveller, defective in emotional breadth, inhumane, and limited in intelligence. In fine he is a stupid but highly emotional man. And he has been loose on the poor British economy for a decade. What replaces him can hardly be worse.

Previous page

Previous page