Sesquicentennial

Raymond Keene

I AM OFTEN ASKED whether Nigel Short is the first British player to contest a world championship. The answer is yes, though a slightly qualified one. In 1890 Isidor Gunsberg challenged the world champion Steinitz in New York. Steinitz was undoubtedly world champion, and he proved that by winning the match, but was Gunsberg British? He was actually born in Budapest and did not emigrate to London until he was 22. To regard Gunsberg as British would be similar to regarding Kor- chnoi as Swiss, or Spassky as French. Gunsberg represented Britain, but I think it would be unfair to Nigel to say that he was a British player.

A more complicated case is that of Howard Staunton, the dominating figure in the early and middle period of Queen Victoria's reign. Staunton was the epitome of Victorian imperial self-confidence and grandeur. He organised the first interna- tional tournament, that of London in 1851, was a prolific writer of books and chess columns and in his spare time he was a Shakespearian scholar who edited a three- volume set of the Bard's works. From 1843 until his setback in the London tournament of 1851, when he came in only fourth, Staunton was universally regarded as the strongest player of his day, 'the champion', but there was no officially recognised world championship title. This had to wait until 1886, when Steinitz claimed it, and repeatedly defended it after winning his match against Zukertort.

Nevertheless, Staunton's match victory against the champion of France, described as 'The Grand Match' between England and France, at the Café de la Regence in Paris in 1843 was the prototype for all modern world championship matches. The winner of the first 11 games was to be the victor, and the eventual length of the match corresponded closely with that of modern world championship play, where a maximum of 24 games per match has been the accepted norm. The headlines of the day showed that Staunton was capable, just as Nigel Short is now, of making chess headline news: 'In the chess clubs of the country the greatest excitement prevailed and the games, as and when received, were played over and over'. Just as Nigel Short now has lent his name to an advertising campaign for Heineken, so Staunton, realising the advantages of product en- dorsement, lent his name to the Staunton pattern chess pieces, now used universally in important competitions.

Staunton — St Amant: Paris 1843; Benoni Defence.

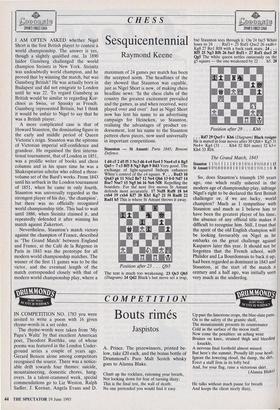

1 d4 c5 2 d5 f5 3 Nc3 d6 4 e4 fxe4 5 Nxe4 e5 6 Bg5 Qa5+ 7 c3 Bf5 8 Ng3 Bg6 9 Bd3 Very good. The exchange of light-squared bishops enhances White's control of the e4 square. 9 . . . Bxd3 10 Qxd3 g6 11 N1e2 Bel 12 Ne4 Qb6 13 0-0 Nd7 14 Bxe7 Nxe7 15 Ng5 h6 16 Ne6 Nf8 Repelling the boarders. For the next five moves St Amant defends most accurately. 17 NxfS RIM 18 b4 cxb4 19 cxb4 Kf7 20 Khl Kg7 21 f4 Rad8 22 Radl h5 This is where St Amant throws it away.

Position after 23 . . . Qb5 The text is much too weakening. 23 Qc3 Qb5 (Diagram) 24 Qd2 Black's last move set a trap,

but Staunton sees through it. On 24 fxe5 White loses to 24 . . Rxfl+ 25 Rxfl Qxe2 26 exd6+ Kg8 27 Rel Rf8 with a back rank mate. 24 . . . Rf5 25 Ng3 Rf6 26 fxe5 Rxfl+ 27 Rxfl dxe5 28 Qg5 The white queen settles ominously on the g5 square — the one weakened by 22 . . h5. 28 Position after 29 . . . Kho

. . . Rd7 29 Qxe5 + Kh6 (Diagram) Black resigns He is mated in four moves after 30 Qh8+ Kg5 31 Ne4+ Kg4 (31 . . . Kh4 32 Rf4 mate) 32 h3+ Kh4 33 12f4.

The Grand Match, 1843 Staunton 111/211111010101/2101/21/200113 StAmant001/200000101011/2011/21/2110 8 So, does Staunton's triumph 150 years ago, one which really ushered in the modern age of championship play, infringe Nigel's right to be declared the first British challenger or, if we are lucky, world champion? Much as I sympathise with Staunton and much as I believe him to have been the greatest player of his time, the absence of any official title makes it difficult to recognise him. Still, I trust that the spirit of the old English champion will be looking favourably on Nigel as he embarks on the great challenge against Kasparov later this year. It should not be forgotten that the French school, with Philidor and La Bourdonnais to back it up, had been regarded as dominant in 1843 and Staunton, at the start of the match a century and a half ago, was initially seen very much as the underdog.

Previous page

Previous page