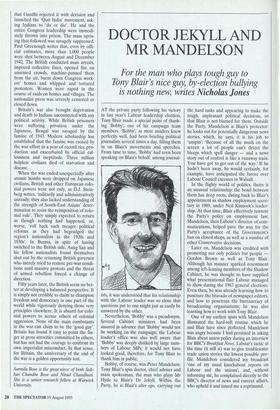

DOCTOR JEKYLL AND MR MANDELSON

For the man who plays tough guy to Tony Blair's nice guy, by-election bullying

is nothing new, writes Nicholas Jones AT the private party following his victory in last year's Labour leadership election, Tony Blair made a special point of thank- ing 'Bobby', one of his campaign team members. 'Bobby', as most insiders knew perfectly well, had been briefing political journalists several times a day, filling them in on Blair's movements and speeches. From time to time, 'Bobby' had even been speaking on Blair's behalf: among journal- *sts, it was understood that his relationship with the Labour leader was so close that questions put to one might just as easily be answered by the other.

Nevertheless, 'Bobby' was a pseudonym. Several Cabinet ministers had been assured in advance that 'Bobby' would not be working on the campaign; the Labour leader's office was also well aware that 'Bobby' was deeply disliked by large num- bers of Labour MPs; it would not have looked good, therefore, for Tony Blair to thank him in public.

Bobby, of course, was Peter Mandelson: Tony Blair's spin doctor, chief adviser and main spokesman, the man who plays Mr Hyde to Blair's Dr Jekyll. Within the Party, he is Blair's alter ego, carrying out the hard tasks and appearing to make the tough, unpleasant political decisions, so that Blair is not blamed for them. Outside the Party, Mandelson is Blair's protector: he looks out for potentially dangerous news stories, which, he says, it is his job to `unspin': 'Because of all the mush on the screen a lot of people can't detect the bleeps which spell danger — and a news story out of control is like a runaway train. You have got to get out of the way.' If he hadn't been away, he would certainly, for example, have anticipated the furore over Labour Council excesses in Walsall.

In the flighty world of politics, theirs is an unusual relationship: the bond between them has deep roots, dating back to Blair's appointment as shadow employment secre- tary in 1989, under Neil Kinnock's leader- ship. At that time, Blair effectively rewrote the Party's policy on employment law; Mandelson, then Labour's director of com- munications, helped pave the way for the Party's acceptance of the Government's ban on closed shops, as well as a number of other Conservative decisions.

Later on, Mandelson was credited with promoting not only policies but people — Gordon Brown as well as Tony Blair. Although his manner sparked resentment among left-leaning members of the Shadow Cabinet, he was thought to have supplied what presentational flair Labour managed to show during the 1987 general elections. Even then, he was already learning how to puncture the bravado of newspaper editors, and how to penetrate the bureaucracy of broadcasting organisations; he was also learning how to work with Tony Blair.

One of my earliest spats with Mandelson illustrated the hard-soft routine which he and Blair have since perfected. Mandelson was angry because I had persisted in asking Blair about union policy during an interview for BBC's Breakfast News. Labour's tactic at the time (it still is) was to give troublesome trade union stories the lowest possible pro- file. Mandelson considered my broadcast 'one of my usual knockabout reports on Labour and the unions', and, without informing me, he complained directly to the BBC's director of news and current affairs, who upheld it and issued me a reprimand. Meeting Blair a few weeks later, I inquired about the reasons for his com- plaint. Blair said he had not seen my tele- vision report, but had vaguely heard something about it. On observing rather ruefully that Mandelson had known pre- cisely where to send his complaint for max- imum impact, Blair gave me one of his now famous grins, replying, 'That is pre- cisely why Peter Mandelson is a star.'

During last month's Littleborough and Saddleworth by-election, Mandelson showed how far he — and Tony Blair — have come since then. To the discomfort of old-fash- ioned Labour MPs such as Richard Burden (who complained about New Labour's new tactics in last week's New Statesman), Man- delson aimed from the beginning to under- mine the credibility of the Liberal Democrat candidate, Chris Davies. His claim that Davies was soft on drugs attracted most attention, but it was only one of several well thought-out ruses. A week before polling day, Davies was challenged for describing himself as a 'self-employed marketing con- sultant'. Labour's demand for clarification was timed to coincide with the Westminster debate on Lord Nolan's recommendations: the very words 'marketing consultant' would, it was hoped, connote sleaze.

Even more impressive was Mandelson's manipulation of journalists, whom he sub- jected to withering put-downs. David Ward of the Guardian, for example, was singled out after having written that Labour's campaign had eschewed radical- ism under 'the Dior-shirted generalship of Peter Mandelson'. This was rubbish, Man- delson announced: the shirts were not really Christian Dior, but fakes.

But although they were perpetrated by Mr Hyde, there was no doubt that Dr. Jekyll approved of these tactics too. At Labour's post by-election news conference, Mandelson dismissed the Liberal Democrats' criticism of his use of 'dirty tricks': 'The days of sitting out by-elections of this kind are over . . . This is not the last word in our by-election campaigning, it was only a dress rehearsal.' That evening, Tony Blair told Channel Four News that there had been a lot of exagger- ated humbug about Labour's tactics, and he did not think 'hard' competition for votes would rule out a dialogue with the Liberal Democrats. And after all, Mandel- son had taken Labour to within 2,000 votes of a sensational by-election victory.

Mandelson's application and dedication cannot be faulted. When he tries to unrav- el or correct a news story he never lets go, never bottles out. Once, dissatisfied with my BBC television reports, he called no fewer than five times in one day. Nor can anyone fault his loyalty. When asked about his pseudonymous role in Tony Blair's leadership campaign, he acknowledged that he had been working for Blair throughout. 'What is important is that I should look after Tony Blair's interests and policies. It is a relationship governed by our friendship. We are chums.'

Mandelson has also, at least until last week's series of outbursts in the New Statesman and elsewhere, been very suc- cessful in his main task — namely, keeping the Labour Party in line. He takes delight, for example, in contrasting Blair's hitherto firm grip on the Labour Party with Tory disarray. Immediately after the Fresh Start group of Conservative Eurosceptics attacked John Major last June, Mandelson expressed his amazement: 'I have just said to Tony I can't imagine members of the parliamentary party talking to you like that, being so disrespectful and interrupt- ing your answers.'

Yet Mandelson's closeness to Blair has its price. Because his every utterance is consid- ered to bear the stamp of Blair's authority, his words are sometimes given far more weight than he intends. Not long after the vote to replace Clause Four (for which Mandelson had campaigned extensively), „Gordon Brown was due to give a key speech on Labour's approach to financial services. However, in a lunch-time radio interview Mandelson, when asked about Clause Four, re-opened speculation about Blair's desire to cut the union vote at the party confer- ence from 70 to 50 per cent, in line with the rise in individual party membership.

Immediately, news wires buzzed with reports that Blair's 'close aide' had 'called on the Party's executive to consider cuts in union power'. Gordon Brown's press offi- cer, Charlie Whelan, was vitriolic, swearing out loud about Mandelson, criticising him roundly for allowing his interview to over- shadow Brown's speech. At tea-time, news bulletins were predicting that Blair might again put his leadership on the line in order to cut down the union vote, and when I ran into Mandelson I asked him about it. He snapped, 'That PA story is a load of bollocks and you know it. I have not "called" for anything. All I said was that the new membership figure means that a decrease in the union vote will now be considered. That is fact.'

To be fair, all that Mandelson had done was to state openly what he had drafted briefs on privately. But by going on the record in a radio interview he had provided public confirmation of Blair's plans and reinforced left-wing suspicions that he was influencing policy decisions. In fact, last month's national executive meeting did agree to seek the October Party Confer- ence's approval for a reduction to 50 per cent in the union vote. So the PA report, although premature, was not 'bollocks' after all: Blair's spin doctor can usually be relied upon to get it right. Which is not sur- prising, since it appears that Blair's spin doctor really does, however often he may deny it, speak for Tony Blair.

Nicholas Jones is a BBC political correspon- dent and author of Soundbites and Spin Doctors, published by Cassell at £17.99.

Previous page

Previous page