Exhibitions

Turner in the North of England, 1797 (Harewood House, Nr Leeds, till 8 June)

Go north, young man

John Whitley

It's rare to be able to spot exactly the moment an artist jumps the divide from being a promising technician into someone of exceptional talent. But the importance of this show — apart from the simple delight of being able to look at a batch of relatively unseen Turner watercolours — is that it does just that.

When the 22-year-old Cockney set out from London on his trip north to some of the wildest country this side of the Alps, just after Napoleon had marched tri- umphantly through Italy to Vienna, he was known only to a small group of connois- seurs as a skilled journeyman of the pic- turesque. When he returned two months and 1,000 miles later, he, like Napoleon, had acquired the confidence of his genius and had begun to glimpse the way in which he could express it.

So this exhibition of the principal paint- ings Turner made on his travels, along with accompanying sketches and notebooks, acts like a series of freeze-frames, laying out his development. And the fact they are hung among the sights that inspired them injects an immediacy which inevitably was lacking when they were exhibited, in a modified form, at the Tate earlier this year.

In a sense, they are coming home. It was the shock of his immersion in the huge skies and untamed moors of the north that released Turner's genius and transformed him into the wizard of light and space who has dominated British art ever since and, even today, influences artists as disparate as Andy Goldsworthy and Howard Hodgkin.

Indeed, there's a case for keeping them permanently north of the Trent, perhaps as an amplification of Leeds City Art Gallery's pioneering holding of Early English water- colours, just as the Stone of Scone has been returned to Scotland. For the catalyst was Edward Lascelles, son of the first Earl of Harewood, who was perceptive enough to encourage Turner to make his safari by commissioning him to paint views of the family seat, Harewood House.

Now that all six of these are hung togeth- er for the first time in over a century in the Watercolour Rooms at Harewood we can walk to the artist's exact viewpoint and then stroll inside to check their accuracy; that makes up a little for the absence of those great oils of northern lights that he painted at the end of his life from the rec- ollection of this early trip and which per- force remain in the Tate.

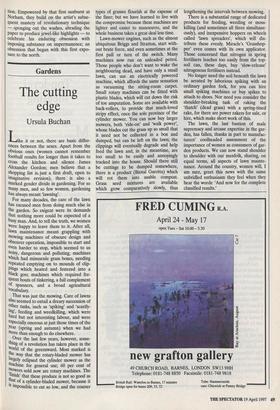

The whole point of this exhibition, how- ever, is precisely the opposite: to show how Turner grew out of being simply a topo- graphical story-teller even as he sat before each vista, scribbling in his notebooks while trying to keep the rain off them. In fact, as the admirably clear captions explain, Turn- er had already had his Damascene conver- sion before he got to Harewood. For some unknown reason, he appears to have bypassed his patron on the way up from London in July and went straight on to Berwickshire where he stumbled on the ruins of Norham Castle, an old frontier 'Norham Castle, Summer's Mom, 1798, by Turner post above a singularly damp elbow of the Tweed.

It seems to have been that setting, though far less wild and romantic than that of Dunstanburgh which he had just visited, which unlocked Turner's genius. He made four watercolours of Norham from more or less the same angle and at the same time of day — just as the sun rose above the bluff on the English side and flashed into the artist's eyes.

His drawings still have the stylised accou- trements that were as obligatory in the pic- turesque genre as they were in Scott's romances: cows standing in the river, a boat crossing, smoke rising from a tumbledown bothy. But, progressively through the water- colours and the pencil sketches that accom- pany them in this show, the subject changes — it's the dazzling light, the iridescence of the moisture-laden sky which excite the painter, not the figurative pokerwork.

Those studies made Turner financially secure as well. `Norham Castle on the Tweed, Summer's Morn' was worked up and shown at the Royal Academy in 1798 and subsequently marketed as an engraving and ever after, as the organiser of the exhi- bition, David Hill, explains in his accompa- nying book Turner in the North (Yale, £29.95), he always had more commissions than he could execute. Indeed, the artist himself acknowledged his debt: whenever his travels took him past the place subse- quently, he'd tip his hat to the ruin.

Although the Norham series inevitably dominates all Turner's work of that period, there are plenty of pictures to discover at Harewood. Those of the Adam mansion and its decrepit 14th-century castle, made on his return journey, aren't as striking but they do show an authority in the handling of the scudding clouds and the distant moors that was missing in the earlier Lon- don work.

The influence of Thomas Girtin and J.R. Cozens still looms over the framing of the relatively unknown study of Harewood Castle (from a private collection) and the shading of the light across the wall; the rev- elations of Norham have not yet been fully absorbed. And the views of Ullswater, Richmond or Sleaford seem routine, as though the obligation to make a correct record comes between artist and subject.

But Harewood caps London by mingling some of the family's own key oils with the drawings and, most of all, by the addition of two of Turner's preparatory 'colour- beginnings' of Bamburgh Castle. These sketches were done 40 years after his visit to try out colour harmonies and back-light- ing for a big watercolour of the great coastal fortress.

That picture, described at the time as `one of the finest water-colour [sic] draw- ings in the world', has since disappeared into the vaults of an American millionaire, but these dabs of dazzling colour, almost abstract but just hinting at a ghostly outline of the battlements, are ample compensa- tion. Empowered by that first sunburst at Norham, they build on the artist's subse- quent mastery of revolutionary technique — sponging out the washes, abrading the paper to produce jewel-like highlights — to celebrate his enduring obsession with imposing substance on impermanence; an obsession that began with this first expo- sure to the north.

Previous page

Previous page