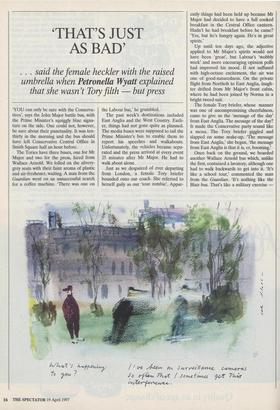

`THAT'S JUST AS BAD'

. . . said the female heckler with the raised

umbrella when Petronella Wyatt explained

that she wasn't Tory filth but press

YOU can only be sure with the Conserva- tives', says the John Major battle bus, with the Prime Minister's squiggly blue signa- ture on the side. One could not, however, be sure about their punctuality. It was ten- thirty in the morning and the bus should have left Conservative Central Office in Smith Square half an hour before.

The Tories have three buses, one for Mr Major and two for the press, hired from Wallace Arnold. We lolled on the silvery- grey seats with their faint aroma of plastic and air-freshener, waiting. A man from the Guardian went on an unsuccessful search for a coffee machine. 'There was one on the Labour bus,' he grumbled.

The past week's destinations included East Anglia and the West Country. Earli- er, things had not gone quite as planned. The media buses were supposed to tail the Prime Minister's bus to enable them to report his speeches and walkabouts. Unfortunately, the vehicles became sepa- rated and the press arrived at every event 25 minutes after Mr Major. He had to walk about alone.

Just as we despaired of ever departing from London, a female Tory briefer bounded onto our coach. She referred to herself gaily as our 'tour zombie'. Appar- ently things had been held up because Mr Major had decided to have a full cooked breakfast in the Central Office canteen. Hadn't he had breakfast before he came? `Yes, but he's hungry again. He's in great spirits.'

Up until ten days ago, the adjective applied to Mr Major's spirits would not have been 'great', but Labour's 'wobbly week' and more encouraging opinion polls had improved his mood. If not suffused with high-octane excitement, the air was one of good-naturedness. On the private flight from Northolt to East Anglia, laugh- ter drifted from Mr Major's front cabin, where he had been joined by Norma in a bright tweed suit.

The female Tory briefer, whose manner was one of uncompromising cheerfulness, came to give us the 'message of the day' from East Anglia. The message of the day? It made the Conservative party sound like a menu. The Tory briefer giggled and slapped on some make-up. 'The message from East Anglia,' she began, 'the message from East Anglia is that it is, er, booming.'

Once back on the ground, we boarded another Wallace Arnold bus which, unlike the first, contained a lavatory, although one had to walk backwards to get into it. 'It's like a school tour,' commented the man from the Guardian. 'It's nothing like the Blair bus. That's like a military exercise — left, right, left, right. Keep on the grid.' The journalists had been complaining that Mr Mandelson prevented any access to Mr Blair. Sightings of the Labour leader were rarer than of Hale-Bopp.

Mr Major, on the other hand, made a point of talking to the journalists on the bus. There has been a curious change in the two parties which the Tories have glee- fully exploited. It used to be Labour that was the 'Peoples' Party' — open, matey, egalitarian, if a bit disorganised. But New Labour has become what the Tories used to be seen as — snooty, distant, authoritar- ian. Tory strategy has been to contrast this with their new-found affinity with ordinary people. They have discovered the h-word. H is for 'human'. The Tories are, New Labour is not.

On the Tory bus things were almost con- sciously shambolic or, as we were repeat- edly told, so 'human'. New Labour had invented campaign jargon for use on the battle buses. Mr Blair, for instance, was known as Tango Bravo, while Mr Mandel- son was 'Bobby', after Bobby Kennedy. I asked the Tory briefer what she was called. `Dragged through a hedge backwards?' But weren't there any Tory code phrases? `Um, there's this one: "It's a milk moment".' What did that mean? 'That the Prime Minister wants to drink a glass of milk.'

I discovered that the Tories did have one other campaign phrase. It was, 'Let's blow this clambake.' As a cowardly mem- ber of the fourth estate, one wanted to blow the clambake more often than not. Whether in Norwich South (a Labour marginal) or on his soapbox in Penzance, Mr Major presented himself as the Peo- ple's candidate. His electioneering was almost Dickensian. This was not without its hazards.

The crowd in Norwich was particularly unfriendly. 'Tory pigs,' it cried, making angry movements as a few game ladies with blue rosettes murmured denials. 'Tory lies!' it repeated. `Go home.' If only one could. Trapped in the throng around Mr Major's bus I was both imprisoned and abused. 'Tory filth,' shouted a middle-aged woman. She raised an umbrella and aimed its spoke directly at my eye. 'No, no,' I Pleaded, 'I'm with the press.' That's just as bad.' The umbrella came down with a whack.

Suddenly Mr Major emerged, followed by Norma. The Prime Minister was as serene as if he were addressing a group of his beloved old maids on bicycles. Norma was wary but had crystalline poise. The Prime Minister began, jovially, 'I hope to talk to some of the imported socialists here.' The socialists were in no mood to be humoured, perhaps because they were not socialists. 'We're members of the Green party,' they yelled. Someone threw a prawn sandwich at Mrs Major (were prawns local produce?). 'This election is starting to Come alive,' commented her husband. If not the longest day, it was fast becom- ing the longest say. The heckling began again. Standards have fallen greatly during this general election — of heckling, I mean. Everywhere we went the heckling was the same: 'Rubbish', 'Tory lies', `Go home'. The hecklers needed a new line. I decided to tell them so. 'Can't you think of something else to shout?' I asked a youth with rope-like yellow hair. 'Yeah,' he said, looking straight at me. 'You f—ing ass- hole.'

Mr Major, astonishingly, seemed to enjoy it all. He certainly couldn't complain about not being the underdog. While his aides cowered in the bus, he beamed, `That was great. Can't wait to do it again.' Later, I asked him whether he had had the hecklers planted. 'Don't be silly, Petronel- la. Now, why would I do that?' he grinned. One of our next stops was Newmarket, where Mr Major was to have a photo opportunity with some horses. The Prime Minister does not like photographs. A few days before, he had refused to pick up a ball for the BBC camera crew. 'He's con- vinced he's not telegenic and then he wor- ries about the headlines — "Major drops the ball, etc.",' explained an aide. Obvi- ously he could think of no derogatory headlines involving horses, for he gamely approached them from the rear end. He then did what he likes doing best — he patted. He patted them again. He kept on patting them, and, unlike most of the elec- torate, they stood still. In between the patting, I asked him how he thought the campaign was going. 'Very well. I know there has been a break- through. Labour is unravelling. I sense, no, I know that people are shifting.' (Or did he say shifty?) At various intervals, the Tories gave us white boxes which contained things to eat. It was difficult to determine from what species the things had originated. 'What does Mr Major eat?' I asked. An aide said, `Lunch.' Of wine and beer, however, there was plenty. 'We aren't sub-human teeto- tallers like Mandelson and the rest,' said the aide. There was that h-word again. `John always has two glasses of chablis on the evening flight. And often some red.'

But this time it was evening and the bus was powering along towards Huntingdon for Mr Major's adoption meeting. We had been powering along for a long time. Sud- denly someone realised that we were going in the wrong direction — back to London. The Tory briefer was blushingly apologetic. `Oh dear, oh dear, I just didn't notice.' The bus reversed to general hilarity and shouts of 'Tory U-turn!'. 'If you were with Blair you wouldn't be allowed to be rude,' joked the briefer.

After an hour or so of driving in the right direction, we finally arrived at Mr Major's constituency. Surely nothing further could go wrong? It did. The bus driver was unable to find the building where the adop- tion meeting was being held. Eventually, the Tory briefer leapt out and hailed a taxi. We followed that cab. `So sorry,' the briefer said afterwards, with an ingratiating smile, 'These things happen.' True. But one couldn't help wondering a little whether the episode had just 'happened'. It was, after all, so human.

'...and! will shower you with all you desire — up to the limit of my Access card.'

Previous page

Previous page