Exhibitions 2

Van Dyck

(Royal Academy, till 10 December)

Unmistakable splendour

Andrew Lambirth

Van Dyck is back in London with a vengeance. On the 400th anniversary of his birth, Sir Anthony Van Dyck, ultra-sophis- ticate and court painter to Charles I, is being roundly feted in the city in which he spent most of the last nine years of his life. Three exhibitions celebrate his quater- centenary, and chief among them is the sumptuous retrospective at the Royal Academy, which comes, primed with suc- cess, from the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten in Antwerp, Van Dyck's home town. More than 100 works, from all periods of his career, pay tribute to this exceptional craftsman, and form a grand pageant of unmistakable splendour.

Although we think of Van Dyck as an English painter, he was a true cosmopoli- tan, who followed his master Rubens to England and only settled here because this was where the work was. Something of a child prodigy, he had been apprenticed at the age of ten to the little-remembered Hendrick van Balen, set up his own studio aged 17, and then became Rubens's chief assistant. He visited England briefly in 1620 before spending four years in Italy, princi- pally studying Titian. During this time he developed his skills as a portrait painter, and flitted about Europe in search of com- missions. Even after he semi-settled in England in 1632, he continued to travel, and in the year of his death was negotiating for a secure position in France.

The English are said to be obsessed with landscape painting, but historically speaking it would be truer to say that the portrait has longer been a favourite. The demand for Van Dyck portraits was unceasing, which meant a workload which no doubt helped to undermine his health. In all, he was responsible for something like 400 English portraits in seven-and-a-half years — a remarkable though uneven body of work which constitutes a poignant record of a gilded but doomed society on the brink of civil war, and a particularly notable moment of artistic patronage and connoisseurship.

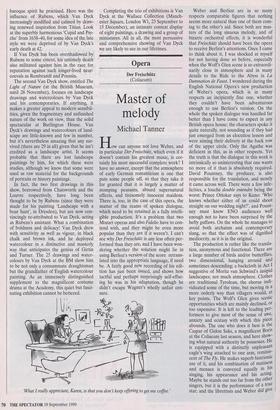

Van Dyck was a master of drapery paint- ing, adept at conveying the weight and A coastal landscape with trees and ships, by Van Dyck, on show at the British Museum `Queen Henrietta Maria with Jeffrey Hudson and an Ape, 1633, by Van Dyck, at the RA sheen of fabrics, as one might expect from the son of a silk and cloth merchant. Even if the drapery was entrusted to an anony- mous assistant, Van Dyck would have been vigilant. He paid attention to details, not just to the more obvious head and hands. Look at the wonderfully ruched and ruffled stuffs, the lace and satin, the prototype platform boots in soft swagging leather. With some portraits, such as 'The Painter Jan de Wael and his Wife', and `Jean-Charles della Faille', both of 1629, and 'Henry Danvers, Earl of Danby' (1633-5), there is real give-and-take between sitter and artist. A visible dialogue between formal public mask and deeper characterisation emerges, between self-pre- sentation and self-disclosure. Idealisation, particularly in the images of royalty, inevitably plays its part. Undoubtedly, boredom led to repetition (and vice versa), and many a portrait is simply the delin- eation of a foppish facade. Nevertheless, Van Dyck almost single-handedly invented the image of the proud, refined and elegant aristocrat, and it was this that exercised a profound influence on subsequent British portraiture, extending from Reynolds and Gainsborough, to Sargent and Augustus John. In his mythological or history paintings, Van Dyck took risks with anatomy that only a confident and highly skilled artist would attempt. Limbs seem to take off in different directions in 'The Continence of Scipio', to dynamic effect. Likewise in the lively 1627 ex-catalogue study of a horse. Van Dyck enjoyed the freedom to distort for the sake of dramatic movement — the essence of the baroque spirit he practised. Here was the influence of Rubens, which Van Dyck increasingly modified and calmed by draw- ing renewed inspiration from Titian. Look at the superbly harmonious 'Cupid and Psy- che' from 1638-40, for some idea of the late style we were deprived of by Van Dyck's early death at 42.

If Van Dyck has been overshadowed by Rubens to some extent, his untimely death also militated against him in the race for reputation against such longer-lived near- coevals as Rembrandt and Poussin.

The second Van Dyck show, entitled The Light of Nature (at the British Museum, until 28 November), focuses on landscape drawings and watercolours by Van Dyck and his contemporaries. If anything, it makes a greater appeal to modern sensibil- ities, given the fragmentary and unfinished nature of the work on view, than the solid spectacular at Burlington House. Van Dyck's drawings and watercolours of land- scape are little-known and few in number, but it's nevertheless amazing that any sur- vived (there are 29 in all) given that he isn't credited as a landscape artist. It seems probable that there are lost landscape paintings by him, for which these were studies, although we know that some were used as raw material for the backgrounds of portraits or history paintings.

In fact, the two first drawings in this show, borrowed from Chatsworth and the Louvre respectively, have long been thought to be by Rubens (since they were made for his painting 'Landscape with a boar hunt', in Dresden), but are now con- vincingly re-attributed to Van Dyck, acting as Rubens's assistant. What a combination of boldness and delicacy! Van Dyck drew with sensitivity as well as vigour, in black chalk and brown ink, and he deployed watercolour in a distinctive and masterly way that anticipates the genius of Girtin and Turner. The 25 drawings and water- colours by Van Dyck at the BM show him to be not only a consummate draughtsman but the grandfather of English watercolour painting. As an immensely distinguished supplement to the magnificent costume drama at the Academy, this quiet but fasci- nating exhibition cannot be bettered. Completing the trio of exhibitions is Van Dyck at the Wallace Collection (Manch- ester Square, London Wl, 23 September to 15 December), an intimate context display of eight paintings, a drawing and a group of miniatures. All in all, the most persuasive and comprehensive showing of Van Dyck we are likely to see in our lifetimes.

Previous page

Previous page