Exhibitions 2

American Art 1930-70 (Lingotto, Turin, till 31 March)

Unmistakable evidence

Giles Auty

Turin My predilection for hospitals in less than convenient places continues. Nor, the views of my fellow critics notwithstanding, was it the shock of a first sight of American Art 1930-70 at the magnificently converted old Fiat factory in Turin which altogether explains my incarceration here. The initia- tive of Fiat in mounting such a huge and exemplary show in a space of unrivalled grandeur deserves nothing but commenda- tion. What American museums, critics and collectors chose to consider significant dur- ing the period in question is not within my power nor that of the sponsors to dispute. The established names in modern Ameri- can art are trotted out and represented at least moderately fairly, generally by more than one work.

What mikes the show so fascinating is that it demonstrates sequentially the estab- lished modernist, museum view of artistic evolution. The interior space is so vast that from certain vantage points one can see works from each of the decades simultane- ously. One is aware, above all, of the pro- ' pounding of critical theories: the word is made flesh at Lingotto on a remarkable scale. I am especially grateful for the expe- rience because it demonstrates unequivo- cally much of the wrong-mindedness of the theories in question. For once the proof is visual rather than verbal and theoretical. The art, if it were truly representative, sig- nals the central flaws of the theories it demonstrates. We begin with the generally modest scale and accomplishments of American figurative painters from the Thirties and end with the more inflated scale and pretensions of American figura- tive painting from the late Sixties. In between lies the screaming visual void of Abstract Expressionism and Pop, Hard- Edge and Colour-Field, Minimalism and Conceptualism. Much of what we see here is as indifferent, arrogant and careless in terms of execution as it is of thought. Thus John Baldessari's pompous, hand-painted word-piece contains a grammatical error so elementary as to make a primary school pupil blush: this from a West Coast pseudo-philosopher who enjoys virtually unparalleled influence in what passes for contemporary thinking in American art.

I take no chauvinistic pride in the com- parisons strategic insertion, at appropriate chronological intervals, of works by British artists of the stature of Sickert, Bomberg, Spencer, Nicholson and Freud might point up at Lingotto against those of their Amer- ican contemporaries who are priced more highly, nevertheless, in the international marketplace. The international pricing of works of art is merely another example of the collective insanity which infests the realms of modern art. The market's exis- tence is like that of a huge, sudsy bubble which requires the continuous introduction of warm air to sustain. There is plenty of the latter commodity in the exhibition cata- logue. By coincidence, I am reading this at the same time as a book with an unprepos- sessing title which someone brought me recently from California. This is Alice Goldfarb Marquis's The Art Biz, which was published in the USA last year by Contem- porary Books of Chicago. The author is an art historian who is less than sympathetic to the roles played in recent American art by collectors and critics, museums and dealers. Nor is she afraid to name names in a text which excoriates the American mod- ern art establishment. I wonder she retains both kneecaps.

The exhibition opens quietly but quite satisfyingly with American art of the post- Depression years. Ralston Crawford, Isabel Bishop, Grant Wood, Charles Sheeler, Reginald Marsh and Edward Hopper pro- vide images of an era which are often poignant and authentic in feeling while sel- dom aspiring to the condition of high art. While Crawford's 'Electrification' seems little more than a successful essay in high school graphics, Bishop and Hopper seek more satisfying goals than the limited, illus- trational techniques and popular sentimen- tality of 'social' paintings by such as Guglielmi, du Bois and Gropper. At one point the catalogue tells negatively of the 'specter [sic] of European art' as though

dealing, in more recent times, with the threat posed by the Japanese car industry. By fleeing and resisting the great European tradition, American artists rejected an informing heritage which might have helped stamp their work with authority as well as authenticity. Edward Hopper is the major American realist of this century yet could never compensate simply by feeling for what he lacked in technique. While seeking individual identity, what is to be gained by rejecting knowledge which informs?

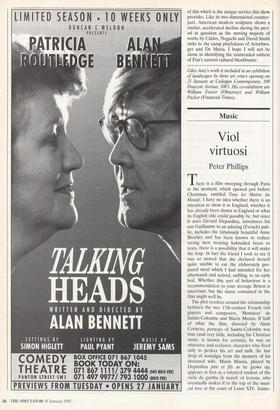

Then and subsequently, American art showed itself willing to pay too high a price simply for the dubious attribute of differ- ence. Sometimes this seemed the sole qual- ity which might be claimed legitimately. American modern art has overvalued for- mal novelty consistently; indeed, the spread of this unintelligent emphasis has had repercussions elsewhere than in America. However limited it may have been, the art of the Thirties and Forties had an often complex pictorial resonance which can still satisfy the eye. All too soon this was to be abandoned in the blind pursuit of largely polemical principles. The critics Greenberg and Rosenberg stoked runaway fires here. Individual works representing the achieve- ments of Pollock and de Kooning hold their ground but the examples chosen to promote the likes of Gottlieb, Motherwell, Newman and Still do their reputations the reverse of any service. Meanwhile the art of Cy Twombly looks more redolent of self- abuse than self-discovery. Reinhardt and Rothko show sensitivity to idea and materi- al but this places them in a minority. The emptiness and arrogance of Noland, Rauschenberg and others demonstrates the penalty of repudiating past guides yet, com- pared with the subsequent aesthetic vacuity from the Pop movement of such as Indi- ana, Rosenquist and Wesselmann they emerge as positive paragons. Aesthetic, pictorial and moral senselessness gather further force in the hands of Warhol and others. Whatever the sophistries of theory, the pictorial evidence presented is incon- trovertible and it is the unmistakable sight 'The Subway', 1950, by Georges Tooker, from the Whitney Museum, New York of this which is the unique service this show provides. Like its two-dimensional counter- part, American modern sculpture shows a similar, accelerated decline during the peri- od in question as the moving majesty of works by Calder, Noguchi and David Smith sinks to the camp playfulness of Artschwa- ger and De Maria. I hope I will not be alone in identifying the unintended subtext of Fiat's current cultural blockbuster.

Giles Auty's work is included in an exhibition of landscapes by three art critics opening on 21 January at Cadogan Contemporary, 109 Draycott Avenue, SW3. His co-exhibitors are William Feaver (Observer) and William Packer (Financial Times).

Previous page

Previous page