ZSA ZSA GABOR KNEW MY FATHER

John Simpson recalls a most unusual

weekend, over 30 Christmases ago in Casablanca

`HAVE YOU seen that extraordinary woman over there?' I asked hoarsely. `Dad?' I added; I was 18, and never quite knew what to call my father. The band, three men in fezzes, ended their indefin- ably Arabic rendering of 'As Time Goes By': it seemed natural enough in a Casablanca nightclub. The striking blonde at the table on the far side of the restau- rant had been swaying in time to the music; now she ruffled the curly black hair of the man she was with. My father looked at her for the first time.

`Ladies and gentlemen,' announced the manager, walking out onto the dance floor and speaking into the microphone like a crooner. His English had a heavy accent. `Welcome to New Year's Eve at the Ski Chalet.'

`Good God,' said my father, still looking at the woman opposite, 'that's Zsa Zsa Gabor.'

She could tell she was being talked about. They made eye contact. `Tonight,' pursued the manager, 'we offer you a special Norwegian delicacy: a snow goose which only flies across the Arc- tic once a year, at Christmas.' `How extraordinary,' I remarked chattily, `to come all the way to Morocco and eat a bird from Norway.' `Absolutely,' my father answered. He wasn't listening. He was still looking at Zsa Zsa Gabor, and Zsa Zsa Gabor was look- ing at him. She shook her head crossly when her companion said something to her. Then she raised an eyebrow in the direction of the dance floor.

`Mind if I have a quick dance, old chap?' `I didn't know you danced.'

There was a lot I didn't know.

We were in Casablanca as refugees from the cold. England was going through the dreadful winter of 1962. In our vast, uneconomic house in Suffolk overlooking the North Sea, the exposed pipes had frozen as hard as concrete and the Aga was like an icy coffin in the corner of the kitchen. My father and I were on our own; his business partner, who was like a second father to me, was spending Christmas with his family. We wandered round the house in overcoats, with scarves tied round our

heads like the old women at Saxmundham market. None of the lavatories worked, so we used the East Anglian Daily Times instead, then wrapped everything up and put it in boxes from Fortnum & Mason or Peter Jones. It was my father's idea. Each afternoon we would drive through the white fields to Ipswich, where leather-hard snow the colour of mud lay heaped up in the streets and you had to walk the slick pavements with the care of an old age pensioner. Southwold was closer, but my father felt it was pointless going there.

`Too bloody honest in Southwold,' he said.

So we would park in one of the main shopping streets, and leave the Fortnum's box on the front seat, with the doors unlocked. By the time we had had a cup of coffee the box would always be gone. It was an entertaining alternative to flushing the lavatory, but it only worked as long as we had enough attractive boxes. When we ran out of them, my father announced that we would have to go somewhere warm. As

a kind of sors virgiliana, he opened the newspaper at random. Casablanca was showing at the Rex.

`Marvellous film,' he said. 'Seen it loads of times. That's where we'll go.' He didn't mean the Rex.

Nowadays Casablanca is a big, feature- less industrial city. In 1962 it hadn't changed much from the days of Vichy and Claude Rains. Our DC-9 skidded across the runway where, in theory, Bogart had watched Ingrid Bergman leave with Paul Henreid. After the weeks of snow and ice I had forgotten what gentle sunshine felt like. The smell of burning camel dung, the fuel of the Tuareg, hung in the air. I pulled out my brand-new passport, the first I'd ever possessed, and had it stamped. A man made a chalk squiggle on our suitcases. Then we walked out into the sunlight.

There was an explosion of noise. Cars hooted, people shouted at us, their faces close to ours, hands grabbed at us, at our clothes, at our suitcases.

`Bloody Arabs,' my father shouted, lash- ing out. I could see he was scared. It had never occurred to me before that he could be frightened by anything.

`I just didn't like it when they crowded in on us, that's all,' he said defensively, as we settled into an ancient taxi, a black, police- like Citroen. He didn't look at me, or say any more. I stared out of the window at the shabby buildings which were the same colour as the desert. I wasn't registering them; I was trying to come to terms with the way my father had looked when the porters gathered round him at the airport.

The street became narrower. Alleyways opened up at oblique angles, and in their dark cave-mouths I caught occasional glimpses of beggars, laden donkeys, crip- ples, street vendors. Little lamplit shops sold heaped-up melons and pomegranates, or long chains of bright, meretricious gold. Heavily veiled women made their way through crowds of men in long dishdashes. I caught sight of someone in the window of a tea-house, smoking a hookah.

`Didn't I tell you?' my father said. It was one of his main themes that England was boring and provincial, and that the real world was full of colour and excitement.

Ahead, a sign read 'Hotel du Midi'. The Citroen rattled to a halt in front of it.

`Bit of a dump,' my father said, frowning. But he paid the driver and we got out. An elderly, bent porter with negroid features and startlingly white hair appeared in the doorway and bowed. When he straightened up I saw he had on a very old, very shiny tail-coat, with a grubby wing-collar and black stock. He wore slippers with trodden- down backs, but no socks.

`We'll just get old Deep South here to take our stuff in.'

I had difficulty hiding my laughter.

Up in my room, a fan circled slowly over- head, ruffling the mosquito net which was draped elaborately over the brass bedstead. `The tropics,' I said aloud, to see what the words sounded like.

`Place hasn't changed much from when I was here before,' my father said, as Deep South brought us mint tea in the hotel saloon.

He hadn't told me he'd been here before. When he was 16 he had run away to sea and sailed round the world twice as a P & 0 steward. He never gave me the whole story, just small, inconsequential details: how beggars gathered at the foot of the gangplank in Bombay, chanting `Give it pice'; how it felt to be struck down by prickly heat; how a meatball had rolled off the tray he was taking to a passenger in a heavy swell, and a blind man had trod- den on it. Now, sipping his mint tea and leafing through Le Matin du Sahara, he seemed a different person altogether from the figure he cut in Suffolk; sharper and more formidable. And yet there had been that disturbing moment at the air- port.

`Advert here for a Norwegian restau- rant,' he said, tapping the page with his thick forefinger. 'All-night place. Dancing. New Year's Eve party. Sounds good, eh?'

`Not really.'

`Come on, you'll love it, We might meet some interesting people.'

We met Zsa Zsa Gabor. That is to say, my father did; she scarcely noticed me. When I shook her hand it was warm and strong, and she brought with her an invisi- ble, delicately perfumed cloud. I don't think it had ever occurred to me that a woman of her age might be so attractive.

`I just had to come over and say hello,' she said, and sat down beside my father. `Hello,' my father replied, in the rounded, deeper tones he used when talking to peo- ple he wanted to impress. He sat down again, and arranged her flimsy light blue shawl over the back of the chair. I tried to see him through her eyes: tough, tanned, barrel-chested, and, I supposed, hand- some. Sitting down, you couldn't see that he was only five-foot-eight, six inches shorter than me. He was sensitive about his height.

I looked across the restaurant. Her com- panion, young and dark and scowling, was still there. She caught my look.

`Poor Julien,' she said, in her charming, carefully cultivated accent, her voice as low as my father's. 'I'll tell him to go home.'

She drifted away, leaving a little of the perfumed cloud behind her. My father watched her. I wanted to say how beautiful she was, but blurted out something alto- gether different instead.

`The Oxford scholarship exams are in a week's time. Maybe I ought to go back and do them.' It had been weighing on my mind for some time, but I hadn't known how to break it to him. He'd set his heart on my going to Cambridge; he thought it wrong to want to leave East Anglia.

`Not now, old chap.'

His eyes were on Zsa Zsa Gabor. Morosely, her companion stood up, and Zsa Zsa Gabor kissed him playfully on the ear, looking at my father as she did it.

`You wouldn't mind if I went back?'

`Do what you like, dear old boy. This isn't quite the . .

`So I can do it?'

He didn't answer; the perfumed cloud was back.

We ate our snow goose in constrained silence. It was rubbery and tasteless.

`This they have flown all the way from Norway?' She started telling my father how they prepared smoked goose in Hungary. He murmured something in reply, and she laughed her delightful, pealing laugh. I smiled politely, looking from one to the other. The waiters came round with trays of elaborate party hats: a legionnaire's kepi, a jewelled crown, the steeple hat of a mediaeval princess. I sat there foolishly, wearing mine, while my father danced with Zsa Zsa Gabor.

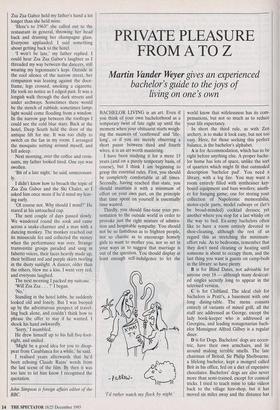

The band struck up a warbling version of `Auld Lang Syne', and we all had to cross hands and sing. No one knew the words Zsa Zsa Gabor held my father's hand a lot longer than she held mine.

`Here's to 1963!' she called out to the restaurant in general, throwing her head back and draining her champagne glass. Everyone applauded. I said something about getting back to the hotel.

`I won't be late,' my father replied. I could hear Zsa Zsa Gabor's laughter as I threaded my way between the dancers, still wearing my legionnaire's kepi. Outside in the cool silence of the narrow street, her companion was leaning against the door- frame, legs crossed, smoking a cigarette. He took no notice as I edged past. It was a longish walk through the dark streets and under archways. Sometimes there would be the stench of rubbish; sometimes lamp- light would come flooding from a window. In the narrow gap between the rooftops I could see the cold blue stars. Back at the hotel, Deep South held the door of the antique lift for me. It was too chilly to switch on the fan in my room. I arranged the mosquito netting around myself, and fell asleep.

Next morning, over the coffee and crois- sants, my father looked tired. One eye was swollen.

`Bit of a late night,' he said, unnecessari- ly.

I didn't know how to broach the topic of Zsa Zsa Gabor and the Ski Chalet, so I asked him once more if he'd mind my leav- ing early.

`Of course not. Why should I mind?' He stared at his untouched cup.

The next couple of days passed slowly. We wandered round the souk and came across a snake-charmer and a man with a dancing monkey. The monkey reached out its minuscule fez and collected the money when the performance was over. Strange transvestite groups paraded and sang in falsetto voices, their faces heavily made up, their brilliant red and purple skirts twirling in the dusty sunlight. A dancer, older than the others, blew me a kiss. I went very red, and everyone laughed.

The next morning I packed my suitcase. Zsa Zsa . . . ?' I began.

`No.'

Standing in the hotel lobby, he suddenly looked old and lonely. But I was buoyed up by the adventurous prospect of travel- ling back alone, and couldn't think how to phrase the offer to stay if he wanted. I shook his hand awkwardly.

`Sorry,' I mumbled.

He drew himself up to his full five-foot- eight, and smiled.

`Might be a good idea for you to disap- pear from Casablanca for a while,' he said.

I realised years afterwards that he'd been echoing Claude Rains' words from the last scene of the film. By then it was too late to let him know I recognised the quotation.

John Simpson is foreign affairs editor of the BBC.

Previous page

Previous page