Party time

Duncan Fallowell

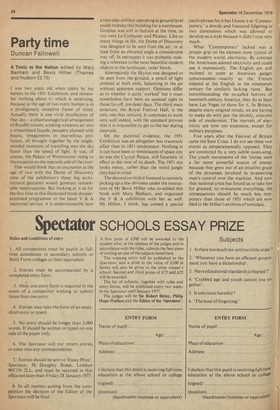

A Tonic to the Nation edited by Mary Banham and Bevis Hillier (Thames and Hudson E2.75) I was two years old when taken by my betters to the 1951 Exhibition, and remember nothing about it; which is surprising, because at the age of two every human is in a prodigiously receptive frame of mind. Actually there is one vivid recollection of that day--a phantasmagorical arrangement of floodlit towers, winking windows set into a streamlined facade, parapets plumed with beasts, integuments in marvellous profusion, all brought together by the singleminded intention of travelling into the sky faster than the speed of light. It was, of course, the Palace of Westminster rising to the occasion on the opposite side of the river.

One would think that an encounter at the age of two with the Dome of Discovery (one of the exhibition's three big architectural gestures) would generate remarkable repercussions. But looking at it as for the first time in this illustrated book/dossier/ extended programme to the latest V & A memorial service, it is understandable how a two-year-old boy operating at ground level could mistake this building for a warehouse. Gropius was still in fashion at the time, so too were Le Corbusier and Picasso. Like so many things in life, the Dome of Discovery was designed to be seen from the air; or at least from an elevated angle a considerable way off. In retrospect it was probably making a reference to the most beautiful modern objects in the landscape, radar bowls.

Alternatively the Sky Ion was designed to be seen from the ground, a pencil of light pointed at both ends, balancing in the air without apparent support. Opinions differ as to whether it quite 'worked' but it must nonetheless have been an unusual sight in those far-off, pre-laser days. The third main structure, the Royal Festival Hall, is the only one that remains. It continues to work very well indeed, with the standard proviso that it is impossible to get to the bar during intervals.

On the pictorial evidence, the 1951 Exhibition was an altogether less traumatic affair than its 1851 predecessor. Nothing in it can have been so reminiscent of space city as was the Crystal Palace, still futuristic in effect at the time of its death. The 1951 site looks messy, rather than the weird jungle they had in mind.

The decorative style it fostered is currently picking up a few devotees under the instruction of Mr Bevis Hillier who co-edited this book with Mary Banham, and organised the V & A exhibition with her as well. Mr Hillier, I think, has coined a special catch-phrase for it but I know it as 'Contemporary,' a dowdy and fractured fidgeting in two dimensions which was allowed to develop as a style because it didn't cost very much.

What 'Contemporary' lacked was a proper grip on the element most typical of the modern world, electricity. By contrast the Americans adored electricity and could use it expressively. The English are still inclined to sneer at American gadget consciousness—exactly as the French sneered at the English in the nineteenth century for similarly lacking 'taste.' But notwithstanding the so-called horrors of twentieth-century America, they do at least have Las Vegas to show for it. In Britain, despite many original minds, we are having to make do with just the shoddy, concrete side of modernism. The marvels of electricity are now too expensive, except for military purposes.

Five years after the Festival of Britain came the Suez Crisis. I do not see these two events as temperamentally opposed. They are connected by a very subtle swan-song. The youth movements of the 'sixties were a far more powerful source of energy because they grew out of an intuitive grasp of the processes involved in re-asserting man's control over the machine. And now that national crisis has forced us to take less for granted, to re-examine everything, the consequences should be much less temporary than those of 1951 which are now filed in Mr Hillier's archives of nostalgia.

Previous page

Previous page