Glimpse of the eternal

Ursula Buchan

We all have our own ideas about what constitutes a thing of beauty. It may be the opalescent lustre on a seashell, or the curve of a child's eyelash, or even the bowling action of Glenn McGrath. For me, it is the flower of the Shirley poppy.

Recently. I went to a press day at a large seed firm's trial grounds. It was a very pleasant occasion, and proved a good opportunity for talking to marketing managers and production experts about new varieties and breeding programmes, seed mixtures and commercial considerations, public taste and private passions. Lunch was laid on. and my mood was mellow as we fanned out across the trial grounds, during an afternoon of rain storms.

Seed trial grounds consist of flat expanses of grass, striped by long rectangu

lar flower beds, full of strong colour in blocks like a child-giant's patchwork blanket. This effect is created by the rows and rows of flowers, raised from seed; both those which the seedsmen already sell to gardeners through their mail-order catalogue, and those called 'experimental', which they are testing, both for appeal and uniformity, before offering them to the public.

Although I am naturally weepy and enjoy a good blub, I do not, in the general run of things, cry while at work. However, there was a moment as I stood beside the ranks of African marigolds (Tagetes erecta) when I could cheerfully have wept. I was beset with the thought that plant breeders had spent so much time, effort and money on developing something so demonstrably ugly and inelegant, if rainproof, as the African marigold, neither easy to fit into a scheme nor capable of producing pleasure on its own. The double flowers look like butteryellow or orange sponges transfixed to the top of truncated stems, and surrounded by coarse, spikily pinnate leaves. Just as there is no word in the English language which rhymes with 'orange', so there is no word which could possibly describe the colour of 'Inca Orange'.

You cannot blame the seedsmen for growing these top-heavy oddities. As I was told with a rueful laugh more than once during the visit, the 'bottom line' generally rules what is grown. If there were no substantial market for African marigolds, they would not appear in catalogues. I do not know whether that says more about our aesthetic sense than our herd instinct.

So, when I stumbled across a pathetic little row of Shirley poppies long past their best. I felt like an ancient but faithful churchgoer finally vouchsaved a heavenly vision. For, in those few, frail, bedraggled flowers was a glimpse of the eternal. To say that they have `tissue-paper' petals is to do a great favour to tissue paper, which is thick and coarse in comparison. Nothing else goes even close, however, in conjuring up the right image created by those crumpled, folded petals. But it is the colours — the pale pink of a dawn sky, the blue-grey of a woodpigeon's wing, the crimson of fresh-spilt blood, the dusty pink of raspberry fool — that so enchant.

The Shirley poppy, of which there are several strains on the market, were first selected from the common scarlet corn poppy, Papaver rhoeas, by the Reverend William Wilks, rector of Shirley in Surrey, a 19th-century gardening clergyman who, among other things, helped rescue the Royal Horticultural Society from oblivion, and is commemorated in the name of the cooking apple 'Rev. W. Wilks'. The original Shirley poppies, single and double, come in colours from white to crimson, scarlet and dull orange, and there are picotees as well.

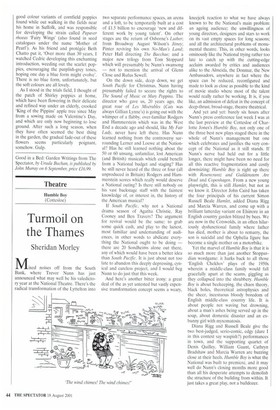

Later, just after the second world war, Sir Cedric Morris, the artist, also selected good colour variants of cornfield poppies found while out walking in the fields near his home in Suffolk, and was responsible for developing the strain called Papaver rhoeas 'Fairy Wings' (also found in seed catalogues under the name 'Mother of Pearl'). As his friend and protegee Beth Chatto put it, 'Over more than 30 years, I watched Cedric developing this enchanting introduction, weeding out the scarlet poppies, encouraging the purplish-grey tones, hoping one day a blue form might evolve'. There is no blue form, unfortunately, but the soft colours are all lovely.

As I stood in the trials field, I thought of the patch of Shirley poppies at home, which have been flowering in their delicate and refined way under an elderly, crooked 'King of the Pippins' apple tree since May from a sowing made on Valentine's Day, and which are only now beginning to lose ground. After such a long season, when they have often seemed the best thing in the garden, the gradual fade-out of these flowers seems particularly poignant, somehow. Gulp.

Good in a Bed: Garden Writings from The Spectator, by Ursula Buchan, is published by John Murray on 6 September, price £16.99.

Previous page

Previous page