Battler for Pleasure

MEET the contestants. On the front of the jacket is Colette of France; her eyes blackened with love, pain, sleeplessness and kohl; her hair tousled as an unmade bed; her nose as sharp and avaricious as that of a Lautrec madame; her mouth a long, closed and narrow wound. Rings gleam on her bent fingers, the window she sits by is shut, the room no doubt redolent of Chanel and cats. On the back of the jacket is Miss Elaine Marks of America, wide-mouthed, with a glitter- ing row of well-polished teeth, a little-girl dress and hair that might well be ruffled by the fresh winds of Oyster Bay. Every book about a writer is a struggle for supremacy, in which the critic attempts to climb to prominence upon the writer's embalmed or battered corpse. Miss Marks has much on her side, youth, enthusiasm, seriousness and several afternoons spent among Colette's manuscripts in the Palais Royal. But the old acrobat eludes her : the bibliography, the notes and the index fail to get her cornered, and all that it is necessary to read about Colette is what she wrote.

Her books, ground out to meet deadlines and pay the rent of country houses, or to buy the meals and clothe the mistresses of the demanding M. Willy, have one predominant theme— pleasure. Pleasure is what her characters re- member of her childhood, the sights and sounds and smells of her countryside, what is instinct- ively achieved by her animals, and what her adults and adolescents struggle towards with the iron self-discipline and the fierce training of a monk in the cloister or an astronaut preparing for orbit. Pleasure is what, in their moments of small but intense tragedy, they grow too old or wise or selfish or cowardly to enjoy. It is a rare theme, and one notably absent from contempor- ary writing.

In an age free of religion it is strange, per- haps, that writers should preserve such a Calvin- istic approach to the sensual world. Characters in our fiction are rarely displayed enjoying them- selves, their visual sense is limited and their tastes blunt. Their love lives, although busy, fre- quently have a grim and puritanical quality re moved from pleasure. This may be a natural and healthy reaction to the late `bon vivant' school of English writing, which once led from a sensual delight in Victorian railway stations to a taste for the memoirs of old eighteenth- century dukes, membership of the Wine and Food Society and a final hedonistic relish for the novels of Miss Nancy Mitford.

With this Vogue world Colette has no connec- tion. Her characters are too classless or un- classed, too unsentimental, and too sharply aware of the dark and humiliating aspects of their world to be comfortable. Here, for instance, she is on the attraction of middle-aged men for young girls : They are numerous, the barely nubile young girls, who dream of being the spectacle, the plaything, the libertine masterpiece of a mature man. It is an ugly desire which they expiate when they fulfil it, a desire which goes together with the nervous disorders of puberty, the habit of nibbling chalk and charcoal, of drinking tooth- powder water, of reading dirty books and dig- ging pins into the palm of one's hand.

To write like this needs no esoteric knowledge of society. It requires a cooler stare at real life than most novelists, male or female, are able to manage.

The theme of pleasure is strongest at the moment her characters either find it vanish, or resign from its merciless demands. Cheri, coming

back to Lea, the woman who taught him all the hard lessons of love, finds an enormous, spread- ing and grey-haired old lady, apparently satis- fied with her lot—and then has nothing left in his empty life. And in La Vagabonde, to me the best of her books but one which Miss Marks finds embarrassing, the music-hall tramp rejects the happy and secure world her lover offers her in the country, and leaves him to go on another tour. 'You are he in whose presence I should no longer have the right to be sad.' Happiness and pleasure have to be retreated from, like the threat of too much sun.

It is true that Colette, like most people, could only write about herself. She had no discernible politics, no general ideas and she certainly wrote Gigi in Paris during the German occupation. Her excuse must be that it is one of her worst books. Her only commitment was to the true examination of one small area of life—but it was an area she explored, both personally and in her writing, with ruthless courage. And of these terrible encounters with pleasure Miss Marks can write: `One may venture to say now that Colette enjoyed a more varied and robust private life than most women or, for that matter, most men.' In a world where the advertising agents and readers of Playboy carefully tot up the total of their affairs, Colette may be allowed to score highly.

Beating her head against the description of an orchid, Colette wrote that it was like 'a bird, a crab, a butterfly, an evil charm, a sexual organ, and perhaps even a flower.' Her books are also probably flowers, fantasies, sexual dreams and bitter truths—and even novels. Miss Marks will have to leave it there. And so, even more so, will I.

JOHN MORTIMER

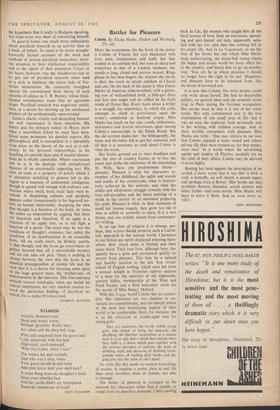

Previous page

Previous page