THE NORTH NORTHAMPTONSHIRE ELECTION. THOSE clergymen who believe or profess

to believe that the worship of intellect is spreading in this country should read the report of the proceedings at the election for North Northamptonshire, which terminated on Monday, and be con- soled. In that county, at all events, the worship of mind is not carried very far. The seat, as our readers are aware, was vacated by the death of Mr. Ward Hunt, and the local mana- gers, possibly afraid of the appearance of a tenant-fanner candidate, with ideas about county government, or the Eastern Question, or rural taxation, hurried forward the election with unusual speed. They looked round for a suitable candidate, and finding that Lord Burghley, the eldest son of the Marquis of Exeter, a young man of twenty-eight, formerly in the Guards, was willing to stand, they accepted him, apparently without the slightest inquiry as to his fitness for political life. He was a Cecil and an eldest son, and would have one of the largest properties in their county, and he would, therefore, be a perfect representative. Whether he could speak or not did not matter, whether ho knew anything either of politics or agricultural life did not signify; he was Lord Burghley and he could vote, and what could Northamptonshire, or at all events, the Tories in Northamptonshire, possibly-desire more? Most unfortunately for the wire-pullers, however, it is an axiom of English political etiquette that a candidate should address the electors; should make some statement of his political opinions, and should, in form at all events, ask for the electors' suffrages. It was essential that Lord Burghley should make a speech or two, and accordingly he did speak, at Thrapston and at Wellingborough, in the following words.—At Thrapston

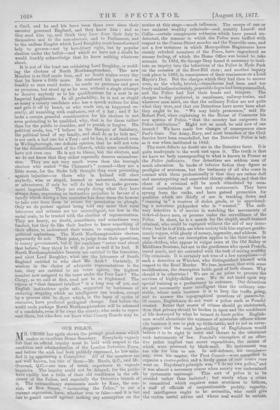

Gentlemen, electors of North Not the torptoushire. After I have been so ably introduced to you, it ie not necessary for we to say much. This is the first speech I have made In my canvassing tour, which has not been a long one, only extending over one day. Mr. Ward Hunt's death occurred so suddenly, that wo wore taken quite by surprise like the enemy in this case. I am sure you have all read my address; you know what my principles nre, and whether you egret) with them or whether you don't don't matter much. These who wish me well and 'wish 'the Conservative cause well will support me, feeling that iu sup- porting me they will be supporting the policy of the Government, and that they are satisfied with the Government in thus far carrying us through tho storm, and that what they *ill do in the future will pro- bably bo much rho same as they have done hitherto. (Hear, hear.) Gentlemen, I must ask you to support me in this election, and I trust that I shall have many of you to back me, I do not knew that I can enliplilen you on any particular subject, and, I do not know that I have more to say. I darosay you have all read Lord Salisbury's speech that he made yostordny nt Hatfield, to the, Conservative working-men there gathered together. He expluined everything a great deal better than I can. II, I. one of the gres,t leaders of the Conservative party, which you probably all know. I am afraid in my canvass I shall not bo able to make the acquaintanee of all you g !riflemen who are going to supped me. I wish to do what I can. This morning I have seen a groat many at Market Harborough, and although I did not speak ia the Corm Exchange, I made the acquaintance of a grout many who, 1 hope, will stick by me in years to come, and carry 1113 through, many more elec- tions. I hope you will excuse the few words I bay° boon able to coy to you. I am glad to see so many here to hoar wo speak and to see me."

At Wellingborough :—

"Lord Burghley

came forward, and was received with cheers. He said : Gentlemen, electors of Northamptonshire, I have been most for- tunate, I consider, in having boon introduced to you, not only by one of city party, and one of the strangest supporters of that party, but also a gentleman who is politically opposed to me has been kind enough to bespeak for me a fair hearing. (Hear, hear.) I am told I that am rather too young to represent you, and that I don't know anything about rolitical matters. (Hear, hear, and applause.) Well, probably I don't, I don't think I do—(boar, hear)—still, I intend to do my best, and with your assistance go to the school Mr. Young has told you of to be educated, and where I shall he. (Derisive cheers.) Gentlemen, as you all seem favourably disposed to listen to me, I hope you will be equally well disposed to give me your support. (Hoar, hoar.) I think you know made emyyo you a tvlf rcs sorts s .0 I f

about rue. I think you know my name bettor than that don't care what his principles are. (Uproar.) He has in

promises. (' And never fulfilled them.') Well, I am glad to hoar you don't expect him to ; it shows you are well disposed to him. I don't Intend to wake you any premises, except to do my duty as your representative, which I hope to be. (' You won't stand much chance horo.') Gentle- men, I feel that I am a candidate in the right cause. (Much. laughter and cheering.) In a cause which makes every country look towards Englund as the starting-point in every policy with regard to the Beet. (' Hear, hear,' and uproar.) Gentlemen, it does not do to make threaten- ing speeches of any sort. As to what this country will do and whether it will go to war, you are as much interested as I am, Probably, many of you have got relations in the Army, and you don't want their noses slit and their oars cut off. (Loud laughter.) I belonged to the Army, and I should be proud to do my share, still, I don't want my nose slit or my oars cut off. (Great laughter.) Gentlemen, I am sorry to detain you so long. (' Go on, go on,' and laughter.) I am not expected to speak in this manner. (' It's too bard work, °Had some one in the crowd.) Yes, I think it is, ropliod his lordship ; I am pretty nearly knocked up. (Laughter.) ' Will you support the diseetablishment .oi the Church?' was called out in a loud voice, and Lord Burghley answered, in a much louder and more emphatic tone, 'No.' Somebody asked him whether he was a Turk, and he quite as emphatically denied the insinuated relationship."

We take these reports from the Wellingborough News, an

but for one circumstance, should believe that a malicious reporter had falsified the speeches, but unfortunately they alarmed some of Lord Burghley's own side. Even they, Tories though they were, could scarcely believe that a man who confessed that he had not an idea of politics, who told an elector in the crowd, when asked about County Boards, that he " had never read of them before," who complained that he had. had only one day in which " to school himself " in such things— ho is twenty-eight, and has had access, of course, by mere right of birth to the best political houses in England—would be elected for a great county, even though it was one, as one elector naively remarked, "in which his father's house was situated," and they issued the following amazing advertise-

ment :-

" North Northamptonshire Election.—Dear Sir,—I, the undersigned„ desire to express regret that, with others, we did invite Lord Burghley to address the assembly in the Thrapstou Corn Exchange on Tuesday last, and confess it a mistake, as his lordship has been so unexpectedly invited to come forward as a candidate to fill the vacancy made by the lamented death of Mr. limit, and was simply on a round of canvass, and had had no thno to coach himself up for political discussion or argument on obtuse subjects, as proposed by my friend Mr. Thus. Atten- borough (no doubt with the best intentions). Lord Burghley is of the right stamp, and will, I doubt not (if elected), prove an efficient and a faithful representative of North Northamptonshire.—Yours truly, Joan EATON, Twywell Villa, August 9, 1877."

Mr. John Eaton and his " others " might have spared their pains. No' apology whatever was required. Tho Liberals, indeed, being by nature critical and disrespectful, made great fun of these addresses, and tried to circulate them very widely, under an impression, we presume, that the electors, seeing what manner of politician their candidate was, would vote against him, but they did not know the farmers of North Northamp- tonshire. A third of the electors marked their disapproval or their indifference by staying away, but 2,261 electors, nearly a clear half, voted for Lord Burghley, and only 1,475 for his opponent, Captain Edgell. The agnostic candidate was re- turned by a two-thirds majority. The electors of the county., in fact, definitely preferred a man who, though, as Mr. Grant Duff says, he " has had all the chances," and will be a Peer, and must as long as he lives be weighted with responsibili- ties which would render any man grave, has not taken the trouble to understand even the rudimentary fads either of politics, or of the municipal organisation of the three counties for which he is already a ma.gistrate,, and in which his stake must one day be so heavy. He

a Cecil, and he and his have been there ever since their ancestor governed England, and they know him ; and so they send him up, and think they have done their duty to themselves and to the non-electors, and to Parliament, and to the endless Empire which Lord Burghley must henceforward help to govern—not by hereditary right, but by popular election under the ballot—and which we have not a doubt he would frankly acknowledge that he knew nothing whatever about.

It is not of the least use criticising Lord Burghley, or scold- ing the electors of North Northamptonshire. The new Member is as God made him, and no doubt wishes every day that he knew a little more. He confessed his ignorance as frankly as man could desire ; he made no pretences and gave no promises, but stood up as he was, without a single attempt to deceive anybody as to his qualifications for a seat in an Imperial Legislature. In all probability, he is not so stupid as many a county candidate who has a speech written for him and gets it off by heart, or who reads one, as happened re- cently, all trembling with confusion, out of a hat ; and if he lacks a certain graceful consideration for his electors in not even pretending to be qualified, why, that is for them rather than for the public to consider, and to punish or forgive. His political credo, too, "I believe in the Marquis of Salisbury, the political head of my family, and shall do as he bids me," is not such a bad one for a Tory ; and he has, it is allowed even in Wellingborough, one definite opinion, that he will not vote for the disestablishment of the Church, while some candidates have not even one. He is not to blame, but the electors, and we do not know that they either especially deserve animadver- sion. They are not very much worse than the borough electors who seated " the Claimant's " counsel—they are a little worse, for the Stoke folk thought they were protesting against injustice—or those who in Ireland will elect anybody, wise or stupid, learned or unlearned, statesman or adventurer, if only he will do his best to make govern- ment impossible. They are simply doing what they have always done, expressing an instinctive prejudice in favour of a family which during a few centuries has done them the honour to take rent from them in return for permission to plough. Only we do protest against being told any more that rural labourers and artisans are too unintelligent, too low in the social scale, to be trusted with the election of representatives. They are heavy, no doubt, sometimes, and sometimes very limited, but they do like their leaders to know something of their affairs, to understand their wants, to comprehend their political aspirations. The North Northamptonshire electors apparently do not. Their point, to judge from their questions, is county government, but if the candidate " never read about that before," they think he will do just as well if ho had. If North Northamptonshire farmers are entitled to the franchise, and elect Lord Burghley, what are the labourers of South England entitled to who elect Mr. Arch ? Certainly, if wisdom in the choice of adequate representatives is the test, they are entitled to six votes apiece, the highest number now assigned to the voter under the Poor Law ? The Clergy, as we said at first, need not be so frightened. The regime of "that damned intellect" is a long way off yet, and English institutions quite safe, supported by buttresses of enduring stupidity which no intelligence can weaken, except by a process akin to those which, in the lapse of cycles of centuries, have produced geological change. Just before the world cools perhaps North Northamptonshire will be ashamed of a candidate, even if he owns the county, who seeks to repre- sent them, but who does not know what County Boards may be.

Previous page

Previous page