ARTS

Country houses

Holding the bridge for fifty years

John Martin Robinson

The National Trust's Country House Scheme

Recently on a visit to Lincolnshire, I was struck by the contrast between the gatehouse of Thornton Abbey, maintained by the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission (`English Heritage'), and Tat- tershall Castle, owned by the National Trust. The former was presented with effortless bad taste; its immediate fore- ground disfigured by a 'picnic area' of rustic benches and tables built of logs, set amidst incredibly naff planting of weeping willows, Cupressus Leylandii and other suburban tat. Tattershall tower on the other hand rose serenely above simply maintained lawns, one or two clipped yews, a moat and properly gravelled paths. Everything to be seen was absolutely appropriate. As Thornton Abbey demons- trates only too clearly, it is very easy to spoil the impact of a building by misplaced attempts to make it attractive to the public. Yet the magnificent effort of the National Trust in presenting its historic houses so consistently well tends to be taken for granted; as is the fact that the National Trust owns and opens a large number of country houses in the first place.

The preservation of historic buildings was not the original purpose of the Trust. The intention of its three founders, Robert Hunter, Octavia Hill and Canon Rawn- sley, in the 1890s was essentially to pre- serve the open landscape, to keep the railways out of the valleys of the Lake District, to hold back the sprawl of the industrial towns, to protect the woodlands and downs near to London and, in the words of Octavia Hill, 'to provide open-air sitting-rooms for the poor'. In 1895 country houses seemed well able to look after themselves.

It was not till after the first world war that increased taxation, and death duties in particular, began to bite. The numbers of houses abandoned or demolished gradually increased year by year and the country house as such came to be seen as an endangered species. A group of people, including Lord Lothian, the owner of Blickling Hall in Norfolk, started to think seriously about this problem. At first they hoped to make it easier for private owners to maintain their own houses. In 1923 the Trust, in vain, pressed the Chancellor of the Exchequer to introduce legislation whereby the owners of historic buildings should receive various tax concessions; and at intervals over the next twelve years the Trust pleaded that positive steps should be taken to introduce preferential rating and taxation for important historic houses. In 1934 Lord Lothian, speaking at the Nation- al Trust AGM, urged the Trust to extend its own work to protect country houses as well as landscapes. He also asked the government to introduce fiscal measures such as the exemption of historic houses and gardens from death duties.

With Lord Lothian's backing, the Trust investigated the possibility of introducing in England a scheme similar to the French Demeure Historique for the preservation of chateaux whereby the French government extended tax concessions and other advan- tages to private owners in return for a degree of public access. The chairman of the Trust, Lord Zetland, advocated this to the Chancellor of the Exchequer but was coldly received. Though the government did not itself wish to take action to save historic houses, it was happy to enable the National Trust to do so on its own initiative and at its own expense.

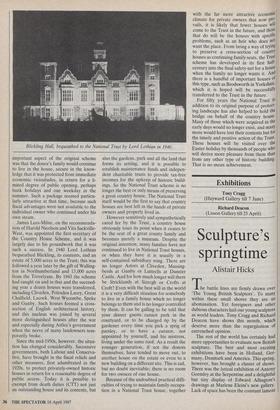

In April 1937 a second National Trust Act was passed by Parliament, which contained a special clause enabling the Trust to acquire and hold land or invest- ments in order to provide from rents and other income for the maintenance and conservation of property. This was the necessary foundation of the National Trust's country house scheme which can thus claim to be fifty years old this month. The aim of the scheme was to enable an owner to transfer his house and contents to the National Trust, together with the estate (or other endowment) so that the Trust could henceforth maintain the property tax-free. (The Trust, being a charity, did not pay income tax or death duties.) An Blickling Hall, bequeathed to the National Trust by Lord Lothian in 1940.

important aspect of the original scheme was that the donor's family would continue to live in the house, secure in the know- ledge that it was protected from immediate economic vicissitudes, in return for a li- mited degree of public opening, perhaps bank holidays and one weekday in the summer. Such a package seemed particu- larly attractive at that time, because such fiscal advantages were not available to the individual owner who continued under his own steam.

James Lees-Milne, on the recommenda- tion of Harold Nicolson and Vita Sackville- West , was appointed the first secretary of the Country House Scheme, and it was largely due to his groundwork that it was such a success. In 1940 Lord Lothian bequeathed Blickling, its contents, and an estate of 5,000 acres to the Trust; this was followed a year later by the gift of Walling- ton in Northumberland and 13,000 acres from the Trevelyans. By 1943 the scheme had caught on and in that and the succeed- ing year a dozen houses were transferred, including Cliveden, Polesden Lacey, Great Chalfield, Lacock, West Wycombe, Speke and Gunby. Such houses formed a cross- section of English architectural history, and this nucleus was joined by several more distinguished houses after the war and especially during Attlee's government when the nerve of many landowners tem- porarily broke.

Since the mid-1950s, however, the situa- tion has changed considerably. Successive governments, both Labour and Conserva- tive, have brought in the fiscal reliefs and other 'measures, first adumbrated in the 1920s, to protect privately-owned historic houses in return for a reasonable degree of public access. Today it is possible to exempt from death duties (CIT) not just an outstanding house and its contents, but also the gardens, park and all the land that forms its setting, and it is possible to establish maintenance funds and indepen- dent charitable trusts to provide tax-free incomes for the upkeep of historic build- ings. So the National Trust scheme is no longer the best or only means of preserving a great country house. The National Trust itself would be the first to say that country houses are best left in the hands of private owners and properly lived in.

However sensitively and sympathetically cared for by the Trust, a country house obviously loses its point when it ceases to be the seat of a great county family and becomes merely a museum. Despite the original intention, many families have not continued to live in National Trust houses, or when they have it is usually in a self-contained subsidiary wing. There are no longer Astors at Cliveden, Massing- berds at Gunby or Luttrells at Dunster Castle. And for how much longer will there be Stricklands at Sizergh or Crofts at Croft? Even with the best will in the world it is a very difficult situation for somebody to live in a family house which no longer belongs to them and is no longer controlled by them. It can be galling to be told that your dinner guests cannot park in the courtyard, or to be charged 6p by the gardener every time you pick a sprig of parsley, or to have a curator, not appointed by yourself, and his mistress, living under the same roof. As a result the younger generation, if not the donors themselves, have tended to move out, to another house on the estate or even to a new building on a different site. This is sad, but no doubt inevitable; there is no room for two owners of one house.

Because of the undoubted practical diffi- culties of trying to maintain family occupa- tion in a National Trust house, together with the far more attractive economic climate for private owners that now pre- vails, it is likely that fewer houses will come to the Trust in the future, and those that do will be the houses with specific problems, such as an heir who does not want the place. From being a way of trying to preserve a cross-section of country houses as continuing family seats, the Trust scheme has developed in its first half" century into the final safety-net for a house when the family no longer wants it. And there is a handful of important houses of this type, such as Brodsworth in Yorkshire, which it is hoped will be successfullY transferred to the Trust in the future.

For fifty years the National Trust to addition to its original purpose of protect- ing landscape has also helped to hold the bridge on behalf of the country house. Many of those which were acquired in the early days would no longer exist, and marl more would have lost their contents but for the timely and positive action of the Trust. These houses will be visited over the Easter holiday by thousands of people who will derive more pleasure from them than from any other type of historic building. That is no mean achievement.

Previous page

Previous page