MAURITIUS

Finding a Formula

NIGEL FISHER, MP, writes: The constitutional conference to decide the future of Mauritius is now in its second week. This beautiful island in the Indian Ocean has a one-crop economy—sugar—and a racially mixed population of three-quarters of a million people. By modern standards its sire and rela- tive viability make it a candidate for indepen- dence, and, if this was the united demand of the political parties in the colony, no Secretary of , State nowadays would think of thwarting it. Bute local opinion is sharply divided and racial fears and tensions complicate the picture.

The seeds of the, problem were sown eighty years ago when Britain began importing in- dentured labour from India to work the sugar plantations in colonial territories. Trinidad, British Guiana and Fiji are other examples. In each case the Indian, population multiplied

rapidly and in most cases is now in the majority. Britain taught her colonies the principle of 'one man one vote' and the Indians are now demand- ing its application in the sugar islands. But the other races in Fiji and Mauritius fear indepen- dence under Indian domination and wish to retain a close association with Britain.

Racial feeling in Mauritius is far less acute and bitter than it was in British Guiana under Dr. Jagan, but that it already exists was shown by the disturbances in the spring of this year when the Governor had to call in a company of British troops (who are still there) from Aden in order to restore calm in the colony. Constitu- tionally, the island has now reached the stage of a ministerial system, just short of full internal government, and is governed by a somewhat uneasy coalition of the four political parties.

The Labour party want independence within the Commonwealth, with the Queen as Head of State; and a defence treaty with Britain. They would agree to any reasonable safeguards for minorities and entrenched clauses in the con- stitution (requiring a two-thirds majority for any changes) which would cover language, religion and the normal human rights provisions.

The Para Mauricien, supported by the Creoles and the French plantocracy, want 'association' with Britain. Ideally, from their point of view, this would include representation at Westminster; special preference for Mauritian immigrants to Britain; and special arrangements by which Britain would take the whole of the sugar crop

p, (as opposed to only part of it) through the Commonwealth Sugar Agreement. They would like the 'association' to be close enough to enable Mauritius to get into the Common Market, if and when Britain herself gets in.

They understand that 'integration' is not possible from the British point of view and they may not, therefore, insist upon representation, special immigration arrangements or a higher sugar quota. Their 'last ditch' position is likely to be that Britain should guarantee the rule of law in Mauritius, and alsb the constitution.

The Independent Forward Bloc are a Hindu Party loosely allied to the Labour party, but rather more left-wing. They will opt for inde- pendence within the Commonwealth.

The Muslim Committee of Action, represent- ing the 120,000-strong Muslim community, are mainly concerned about Muslim representation in the legislature. Although officially uncom- mitted on the independence issue, they have Publicly declined a deal publicly offered by the Parti Mauricien of adequate Muslim represen- -) tation provided the MCA will support it on asso- ciation. If the Labour party will give what the Parti Mauricien has offered, the MCA will sup- Port the Labour party on independence.

Communal rolls in Mauritius would be divi- sive and retrograde; but, owing to the scattered nature of the Muslim community, some method of giving the Muslims representation in the legislature approximately in accordance with their population will have to be devised.

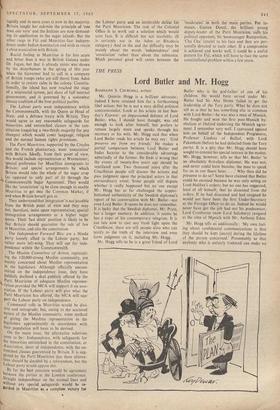

On the main issue, the alternative solutions seem to be: Independence, with safeguards for the minorities entrenched in the constitution; or AAsociation, short of independence, with the en- trenched clauses guaranteed by Britain. It is sug- gested by the Parti Mauricien that these alterna- tives should be decided by a referendum, but the Labour party would oppose this. By far the best outcome would be agreement between the parties at the London conference. Straight independence on the normal lines and Without any special safeguards would be re- igarded in Mauritius as a complete victory for the Labour party and an intolerable defeat for the Parti Mauricien. The task of the Colonial Office is to work out a solution which would save face. It is difficult but not insoluble. (It is certainly not in the Aden or Rhodesia category.) And in the end the difficulty may be mainly about the words 'independence' and 'association' rather than about the substance. Much personal good will exists between the 'moderates' in both the main parties. For in- stance, Gaeten Duval, the brilliant young deputy-leader of the Parti Mauricien, calls his political opponent, Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam, 'Cha Cha' (uncle) to his face and they are per- sonally devoted to each other. If a compromise is achieved and works well, it could be a useful pattern for Fiji, which will have to face the same constitufional problem within a few years.

Previous page

Previous page