Exhibitions 3

I Della Robbia e 1"arte nuova' della scultura invetriata (Basilica di Sant'Alessandro, Fiesole, till 1 November)

Family business

Bruce Boucher

Lcy Honeychurch, the heroine of A Room with a View, knew that she ought to admire Giotto's frescoes in Santa Croce but preferred the terracotta infants by Andrea Della Robbia on the Foundling Hospital. She needn't have been so defen- sive about her taste because those wriggling babies and their angelic siblings had won the admiration of critics as diverse as John Ruskin and Walter Pater; indeed, Ruskin ranked Andrea's uncle, Luca Della Robbia, on a par with Perugino and the young Raphael, his child angels expressing that `one pure and sacred passion which pro- tected Christendom from the ruin of the Renaissance'. The popular culture of Renaissance Italy was shaped by Della Robbia terracotta, encompassing every- thing from statuary to ink wells. One hun- dred and fifty such works are currently on display in an exhibition which Miss Honey- church would have found immoderately stimulating.

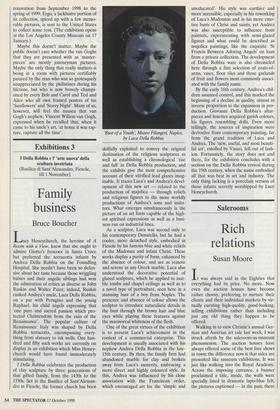

I Della Robbia celebrates the production of clay sculpture by three generations of that gifted family, from the 1430s to the 1550s. Set in the Basilica of Sant'Alessan- dro in Fiesole, the former church has been Bust of a Youth, Museo Filangeri, Naples, by Luca Della Robbia skilfully exploited to convey the original destination of the religious sculptures as well as establishing a chronological 'rise and fall' in Della Robbia production, and the exhibits give the most comprehensive account of their vitrified lead glazes imag- inable. It traces Luca's and Andrea's devel- opment of this new art — related to the production of majolica — through reliefs and religious figures to the more worldly productions of Andrea's sons and imita- tors. What emerges simultaneously is the picture of an art form capable of the high- est spiritual expressions as well as a busi- ness run on industrial lines.

As a sculptor, Luca was second only to his contemporary Donatello, but he had a cooler, more detached style, embodied in Fiesole by his famous blue and white reliefs of the Madonna and infant Christ. These works display a purity of form, enhanced by the absence of colour, and are as remote and serene as any Greek marble. Luca also understood the decorative potential of glazed sculpture, which he applied to mar- ble tombs and chapel ceilings as well as to a novel type of portraiture, seen here in a stunning bust of a boy from Naples. The presence and absence of colour allows the sculptor to introduce naturalistic details in the bust through the brown hair and blue eyes while playing these features against the marmoreal whiteness of the flesh.

One of the great virtues of the exhibition is to present Luca's achievement in the context of a commercial enterprise. This development is usually associated with his nephew Andrea Della Robbia in the late- 15th century. By then, the family firm had abandoned marble for clay and broken away from Luca's austerity, embracing a more direct and highly coloured style. In this, Andrea was influenced by his close association with the Franciscan order, which encouraged art for the 'simple and uneducated'. His style was earthier and more accessible, especially in his reworking of Luca's Madonnas and in his more emo- tive busts of Christ and saints; yet Andrea was also susceptible to influence from painters, experimenting with semi-glazed figures and what could be described as majolica paintings, like the exquisite 'St Francis Between Adoring Angels' on loan from a private collection. The development of Della Robbia ware is also chronicled here through a fine selection of coats-of- arms, vases, floor tiles and those garlands of fruit and flowers most commonly associ- ated with the family name.

By the early 16th century, Andrea's chil- dren assumed control, and this marked the beginning of a decline in quality, almost in inverse proportion to the expansion in pro- duction. Giovanni Della Robbia's altar- pieces and lunettes acquired garish colours, his figures resembling dolls. Even more tellingly, the sources of inspiration were derivative from contemporary painting, far from the grand tradition of Luca and Andrea. The 'new, useful, and most beauti- ful art', extolled by Vasari, fell out of fash- ion. Fortunately, the story does not end there, for the exhibition concludes with a section on the Della Robbia revival during the 19th century, when the name embodied all that was best in art and industry. The only thing lacking is a porcelain version of those infants secretly worshipped by Lucy Honeychurch.

Previous page

Previous page