Exhibitions

Solomon J. Solomon (Ben Uri Art Gallery, till 20 November)

Dry response

Giles Auty

Aweek ago I happened, by chance, to attend a private view at a small art gallery not far from where I live. I had not gone there before but was recognised instantly by the manageress of a local shop from which I had bought quantities of household paint some years ago. 'You're a decorator, aren't you?' she remarked pleasantly, aim- ing to put me at ease in unfamiliar sur- roundings. 'Of course, my husband's a real artist. It's his exhibition that is opening this evening.' I have remarked before that wives, women friends and models often display the pride and aggressiveness of lionesses when involved with artists. Indeed it is for this very reason I feel hesitant when writing about the art of William Cold- stream. It is not just the late artist's female friends and ex-models but armies of Slade- trained women, who absorbed something of the artist's singular painting methods, who wait in the wings to mug any critic unwise enough to question Coldstream's correct place in the hierarchy of art.

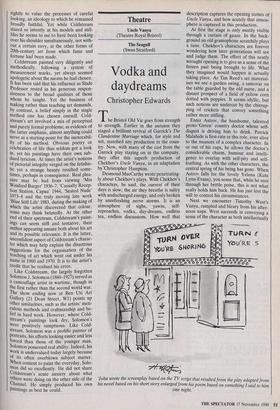

It was Ben Nicholson, I think, who said that looking at Paul Nash's paintings made him long for a glass of water. Coldstream's art has a similarly parched quality, being largely arid in humour, texture and colour, a hue as of dry biscuit predominating. The artist was born in 1908 and died three years ago. His influence was felt widely in the art affairs of this country and he is thus a fitting subject for the present retrospective at the Tate. Many of us have been familiar for years with a small number of Cold- stream's paintings without realising these were some of the best he did. His art strikes me as an entirely foreseeable pro- duct of his conflicts and commitment. It looks passionate in the pains with which it was made but in no other respect. The artist studied at the Slade from 1926 to '1929, when Tonks was in his last years there as Slade Professor. Coldstream assumed this role himself in 1949, retiring finally in 1975. Between those years he served on umpteen influential cultural committees and was greatly respected. Why, then, do I see his art as one of conflict? It was Tonks who taught him 'Casualty Reception Station, Capua', 1944, by William Coldstream rightly to value the processes of careful looking, an ideology to which he remained broadly faithful. Yet while Coldstream stared so intently at his models and still- lifes he seems to me to have been looking over his shoulder simultaneously, not with- out a certain envy, at the other forms of 20th-century art from which fame and fortune had been made.

Coldstream painted very diligently and methodically, following a system of measurement marks, yet always seemed apologetic about the means he had chosen. It has been said that his influence as Slade Professor rested in his generous respon- siveness to the broad qualities of those whom he taught. Yet the business of making rather than teaching art demands, by contrast, a belief simply in the single method one has chosen oneself. Cold- stream's art involved a mix of perceptual and purely formal problems; as evidence of the latter emphasis, almost anything could serve as a starting-point for the inexorabil- ity of his method. Obvious poetry or celebration of life thus seldom got a look in, yet his paintings have their own sub- dued lyricism. At times the artist's notions of pictorial integrity verged on the fetishis- tic yet a strange beauty resulted some- times, perhaps in consequence. Real plea- sure may be had from viewing 'Mrs Winifred Burger' 1936-7, 'Casualty Recep- tion Station, Capua' 1944, 'Seated Nude' 1973-4 and the truly moving late work `Blue Still Life' 1983, during the making of which the artist discovered that colour, some may think belatedly. At the other end of their spectrum, Coldstream's paint- ings can seem stiff and tentative, their author appearing unsure both about his art and its possible relevance. It is the latter, unconfident aspect of Coldstream's charac- ter which may help explain the disastrous suggestions for the organisation of the teaching of art which went out under his name in 1960 and 1970. It is to the artist's credit that he realised his error.

Like Coldstream, the largely forgotten Solomon J. Solomon (1860-1927) served as a camouflage artist in wartime, though in the first rather than the second world war. The show ending now at Ben Uri Art Gallery (21 Dean Street, W1) points up other similarities, such as the artists' meti- culous methods and craftmanship and be- lief in hard work. However, where Cold- stream's paintings look dry, Solomon's were positively sumptuous. Like Cold- stream, Solomon was a prolific painter of portraits, his efforts looking easier and less forced than those of the younger man. Solomon possessed real ability. Indeed, his work is undervalued today largely because of its often overblown subject matter. When content to paint the everyday, Solo- mon did so excellently. He did not share Coldstream's acute anxiety about what others were doing on the other side of the Channel. He simply produced his own Paintings as best he could.

Previous page

Previous page