Sovereign State

A farmer's view

Christopher Harrisson

Many farmers are against the UK staying in the Common Market because, first and foremost, this country should be master of its own destiny. Who rules Britain? Not ourselves if we stay in. We many thousands of farmers believe in parliamentary democracy and the rule' of British law.

Chairmanship of the British Egg Marketing Board and of the International Egg Commission provided me with more than enough experience of the difficulty of trying to work With the bureaucrats of Brussels. It produced the firm conviction that on all counts we are better off with democracy from Westminster. An example of what happens occurred during the sugar shortage when our Minister of Food tried to get extra supplies from Commonwealth countries. The EEC Agricultural Commissioner, Lardinois, stated that the responsibility for supplying sugar to the British people no longer rested with London, but with him in Brussels.

This is by no means an isolated case. By Joining the EEC the UK has given up the right to govern itself to such an extent that it has been said that it is a waste of time for our MPs to ask questions in the House of Commons. Ministers can do nothing or at most no more than promise to do their best. Brussels calls the tune.

The spate of regulations and directions pouring out of Brussels is such that no government has time to examine all the implications, let alone discuss these with the industries concerned when this should be vitally necessary as it nearly always is. Experience has already shown how difficult it is to alter any of these decrees once they have been made.

I am against staying in the Common Market because the past two years of membership have left me worse off than I would have been if we had not been persuaded to join in the first place. Thousands of farmers are with me because their experiences are the same as mine. The rest do not appear to accept the evidence of the facts. They seem to rely on the hope and supposition that all will be well in the end if they will only put a cross against 'In' on the referendum ballot paper.

But I am against also, because the farming System we have built up over the years and particularly since the war has provided, for Price Review commodities, guaranteed prices and assured markets compared with the feasts and famines experienced by European farmers over the same period. Our system has provided the British housewife with a regular supply of top quality food at stable prices year by year in contrast to her Continental counterpart who has had to buy at widely fluctuating prices. Are we to stay in the Common Market and throw such advantages away? I am against on economic grounds because the true facts and figures say 'Out' in face of the arguments based on faith and fantasy put forward by those who would have us vote 'In.'

Has any industry the statistics to show that two years' membership of the EEC has improved its economic position? Certainly not agriculture which has just come through its worst ever annual price review. The unanimous view of the council of the National Farmers' Union is that the results of this 1975 review are quite inadequate, and that for the second year running. For all but three of the commodities concerned, these reviews were under the jurisdiction of the EEC–not of Parliament.

According to NFU president, Sir Henry Plumb, the Union Council could not accept that the review determinations would renew either confidence or security. Unless more was done to restore profitability in the near future, home food production would dwindle at the expense of the whole nation. Over the past year costs of production had risen by a staggering £700 million repeating what had happened the year before. Over these past years costs had risen by 50 per cent. Inflation in the UK at 19.9 per cent made no difference to Brussels which decided on only a 10 per cent increase. But the three commodities still administered from London showed realistic increases of 27 per cent for potatoes, 30 per cent for sheep, and 19 per cent for wool. How much better off would we have been and how much confidence would have been restored if all commodities were still controlled by London?

"The most disappointing feature of the whole of the 1975 review was the failure to adjust the green £ adequately," Sir Henry went on. "The use of an artificially fixed rate instead of the actual value of the £ put UK producers at a double disadvantage. They did not receive the properly converted EEC prices, while those in other Common Market countries were given export subsidies. So far as UK producers were concerned, the system acted as a tax on our exports."

This is the sort of thing the Common Market is giving us in place of the years of stability through the 1950s and 1960s which came as a result of the guarantees of prices and markets brought in by the 1947 Agriculture Act, a foundation laid by two great agricultural statesmen, Tom Williams and Jim Turner, now Lord Netherthorpe. For years now this has been our fundamental agricultural policy, one which is recognised by all political parties. What it means to the industry is stated in the Act itself:

The following provisions of this part of the Act (dealing with guaranteed prices and assured markets) shall have effect for the purpose of promoting and maintaining, by the provision of guaranteed prices and assured markets for the products mentioned in the first schedule to this Act, a stable and efficient. agriculture industry capable of producing such part of the nation's food and other agricultural produce as in the national interest it is desirable to produce in the United Kingdom, and by producing it at minimum prices consistent for the proper remuneration and living conditions for farmers and workers in agriculture and an adequate return on capital Invested in the industry.

Under these guiding principles, the industry expanded steadily until two years ago when membership of the EEC began to make itself felt adversely. The 1947 Act itself set off a veritable explosion in production on our farms. From 1946/47 to 1960/61 the rate of increase was

51 per cent; in the ten years from then to 1971 it was 27 per cent; and between 1971 and 1975 it amounted to 15 per cent. Despite all the difficulties it was still going up.

And what about consumer prices? The retail price index on food jumped from about 169.4 in 1972 to 230.0 in 1974 (1962 = 100), a rise of 60.6 over the first two years of Common Market membership. Before that it took eight years for a similar increase to take place.

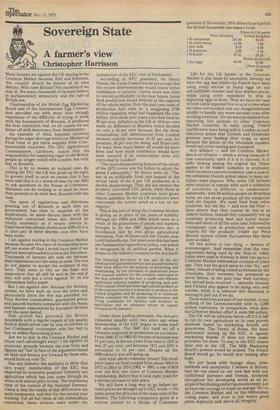

We still have a long way to go before our retail prices are brought up to EEC levels — the same prices for all is one of the main aims of the Market. The following comparison given in a written answer to a House of Commons question in November, 1974 shows how hard hit the British housewife can expect to be:

Prices in UK pence West Germany United Kingdom 1 lb rumpsteak 187.00 83.00 1 lb white bread 17.89 7.94 1 pint milk 9.16 4.50 1 lb potatoes 3.49 3.10 1 lb butter 57.31 24.20 (home produced) 1 doz eggs 44.94 22.90 (New Zealand) 33.60

Life for the UK farmer in the Common Market is also beset by anomalies. Already we have the egg war where the French have been using every excuse to dump eggs on our self-sufficient market and thus depress prices, while using every expedient to stop us exporting eggs to them. Then we have the case of Irish cattle exported live to us at a time when we were overstocked and our slaughterhouses unable to handle any more carcases even after working overtime. Yet we were prohibited from exporting live animals to other Common Market countries. In early spring, French cauliflowers were being sold in London at such ridiculous prices that Cornish and Pembroke growers were feeding their crops to stock because the prices on the wholesale markets would not cover cutting and transport. Any alliance — and the Common Market idea is an alliance — needs a strong measure of true community spirit if it is to succeed. It is sadly lacking among the original Six. There appear to be hidden subsidies in profusion, while for more concrete evidence, take a look at the unilateral French action taken to keep out Italian wine imports. Why some UK farmers seem anxious to remain with such a collection of countries is difficult to understand. Admittedly, with 56 million people on 50 million acres, we can never produce all the temperate food we require. We need food from other countries, but the Six — and now the Nine — have shown that they cannot do this in an orderly fashion. Instead they constantly run up surpluses producing beef and butter mountains and latest of all the wine lake, followed by consequent cuts in production and ruinous returns for the producer. Under our Price Review system violent fluctuations like these were avoided.

All this points to one thing — beware of scaremongers. And remember that the very arguments being used by the `Stay-in' lobby today were used in Norway in their run-up to a Common Market referendum a couple of years ago. They had the good sense to vote 'No,' and today, instead of being ruined as forecast by the Jeremiahs, their economy has prospered as never before. In the past year their currency has twiced been revalued — upwards. Sweden and Finland also appear to be doing very well outside, while it is believed that Denmark is waiting to pull out if we do.

These countries are part of our market, to say nothing of the Commonwealth with its 2,200 million customers. In comparison, what does the Common Market offer? A mere 260 million.

The UK will be infinitely better off if it is left to run its own agriculture on its own proven methods based on marketing boards and guarantees. The Treaty of Rome, the basic instrument setting up the EEC, is against marketing boards. It does not even make provision for them. To stay in the EEC means their end in the UK. The Milk Marketing Board's powers would be pruned. The Potato Board would go. So would that looking after hops.

We are faced with foreign ideas, alien methods and anonymity. I believe in Britain; that we can stand on our own feet with our traditional partners and friends, accepted throughout the developing world as an example of fair dealing and scrupulous honesty. Let us have the courage to stand up and say 'No' to the Common Market and on the referendum voting paper, and trust in our native good sense, ingenuity and, above all, integrity.

Previous page

Previous page