I JOINED THE BARMY ARMY

Lloyd Evans volunteers

to canvass for the Labour party in Tottenham

CALL me a fool but I like to take New Labour at its word. When I heard that 'opportunity for all' is now official party policy, I decided to seize the chance with both hands. Having got the nod from this magazine's editor I infiltrated the Totten- ham by-election team in order to earn a few bob reporting from Labour's inner-city heartlands. There we are. I've come clean right at the start. I hope no one at Labour headquarters raises any objections. On the other hand, I almost hope they do. It'd be fun to see them complaining about some- one masquerading as a socialist in order to advance his own agenda.

The by-election was called after the death of Bernie Grant, the radical left-wing MP known as 'Barmy Bernie' to the tabloids. When I arrived at the campaign nerve-cen- tre in Tottenham I found the Barmy Army busy blowing up balloons. They'd formed a production line. One activist distributed balloons from a box, another inflated them from a helium cylinder, another handed out bits of string, and so on. I had an inkling something symbolic was taking place: a chain-gang of party workers inflating plastic bubbles bearing an empty slogan (Vote Labour) from a tank full of non-flammable, lighter-than-air gas provided by Millbank. Was this new Labour encapsulated or was I just being cynical?

I soon found myself in charge of knot- ting the balloons. I was amazed that a non- member could rise so swiftly through the Labour hierarchy — but, in the party of opportunity, talent talks.

We set up a pavement stall on Totten- ham High Road, a cramped, gusty cause- way bobbing with litter and snorting with buses. It can't be long before the council restyles this street in honour of its deceased MP. The only question is, how? Grant Grove, perhaps. Bernie Broadway. Or maybe just Barmy Boulevard.

We found ourselves in competition with a Marxist splinter-group who had got up early and colonised the best campaigning turf. This is where the Conservatives differ from Labour. Disgruntled Tories tend to hijack the party from within, while Labour's revolting fringes prefer to quit altogether and form doomed little coteries-in-exile. Just three months old, the latest band of splitters is called the London Socialist Alliance (LSA), a name chosen from the Directory of Forgettable Acronyms (DFA), which Millbank makes freely available to all Labour members who are about to disaffili- ate. We eyed each other suspiciously.

I skimmed through our campaign leaflet and found the usual basketful of plati- tudes. Boosting jobs, cutting crime, dou- bling this, halving that. Our candidate, David Lammy, beamed from behind a pair of steel-framed spectacles, an earnest young lawyer with a bland, handsome face, a no-nonsense chin and a row of immacu- late teeth that came billowing off the page like a line of freshly laundered shirts.

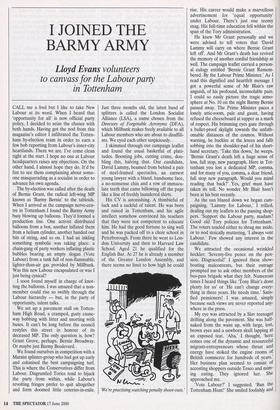

His CV is astonishing. A thimbleful of luck and a sackful of talent. He was born and raised in Tottenham, and his agile intellect somehow convinced his teachers that they were not competent to educate him. He had the good fortune to sing well and he was packed off to a choir school in Peterborough. From there he went to Lon- don University and then to Harvard Law School. Aged 21 he qualified for the English Bar. At 27 he is already a member of the Greater London Assembly, and there seems no limit to how high he could 'We're practising watching penalty shoot-outs.' rise. His career would make a marvellous advertisement for 'equal opportunity' under Labour. There's just one teensy snag. His full-time education fell within the span of the Tory administration.

He knew Mr Grant personally and we were advised to tell voters that 'David Lammy will carry on where Bernie Grant left off'. And Mr Grant's death has revived the memory of another cordial friendship as well. The campaign leaflet carried a person- al eulogy entitled 'Bernie Grant Remem- bered. By the Labour Prime Minister.' As I read this dignified and heartfelt message I got a powerful sense of Mr Blair's raw anguish, of his profound, inconsolable pain. I could so easily picture the tragic atmo- sphere at No. 10 on the night Barmy Bernie passed away. The Prime Minister paces a lonely attic-room, pale and gaunt, having refused the cheeseboard at supper as a mark of respect. His brimming eyes gaze through a bullet-proof skylight towards the unfath- omable distances of the cosmos. Without warning, he buckles at the knees and falls sobbing into the shoulder-pad of his short- hand secretary. 'Take this down,' he weeps. 'Bernie Grant's death left a huge sense of loss, full stop, new paragraph. Here in Tot- tenham you lost a dedicated MP, comma, and for many of you, comma, a dear friend, full stop new paragraph. Would you mind reading that back?' Yes, grief must have taken its toll. No wonder Mr Blair hasn't been at his best recently.

As the sun blazed down we began cam- paigning. Tammy for Labour,' I trilled, dealing out my leaflets to the passing shop- pers. 'Support the Labour party, madam? Good old Tory policies for Tottenham.' The voters tended either to shrug me aside, or to nod stoically muttering, 'I always vote Labour.' Few showed any interest in the candidate.

We attracted the occasional wrinkled heckler: 'Seventy-five pence on the pen- sion. Disgraceful!' I ignored these show- boating malcontents, but their outrage prompted me to ask other members of the bus-pass brigade what they felt. Numerous times I heard things like 'Tony Blair's done plenty for us' or 'He can't change every- thing in three years. He needs time.' Satis- fied pensioners! I was amazed, simply because such views are never reported any- where in the press.

My eye was attracted by a Slav teenager drifting along the pavement. She was half naked from the waist up, with large, lost, brown eyes and a newborn skull lapping at an exposed teat. 'Alla,' I thought, 'here comes one of the dynamic and resourceful migrant-entrepreneurs whose thrust and energy have stoked the engine rooms of British commerce for hundreds of years.' Her business plan seemed to consist of accosting shoppers outside Tesco and mim- ing eating. They ignored her. She approached me.

'Vote Labour?' I suggested. 'Ban the Tottenham Hunt!' She smiled foolishly and angled a glance towards the bald asylum- suclder coiled at her breast. Now you have to admit, it's a highly effective sales pitch. The naked melon catches your eye. The squirming prawn tugs at your heart-strings. And the message couldn't be plainer. 'I had unprotected sex last year. We're all human. Now cough up,' But I'm one of those people who tries to see the broader picture. 'No beg,' I said to her, metronom- ing a chiding finger, 'you make problems for your own people.' She smirked and nodded irrelevantly, holding my gaze with a look of pathetic tenderness. In revolt at my sickening piety I handed her a pound. She drifted up the road towards the LSA whose banners happened to read 'Stop the Scapegoating. Asylum-Seekers Welcome.' To their credit each of them forked out a few coins for the Madonna of the Warsaw Pact.

Immigration is a hot topic in Tottenham, even though no one likes to talk about it A few days later, festooned in Labour stickers and still not a member of the party, I toured a council estate near Turnpike Lane canvassing voting intentions. Many of the residents had come to Britain in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. They'd found jobs and raised children, and they complained to mc that, when they saw families of asylum- seekers fresh off the boat being given free accommodation and welfare benefits, they felt as if their life's work was being ren- dered invalid. I heard this several times from Asians, West Indians and Irish people. No one seemed to favour William Hague's refugee camps but most thought Labour should be much tougher on the new arrivals. A young woman of West Indian origin confided to me in whispers on her doorstep, 'I hope you don't think I'm being racist but it's the Africans who are ruining this country. They've got no manners, no idea of decent behaviour. It's the West Indians that built Britain up and the Africans come over here, rip off the social and we have to pick up the bill.' She could have been an East End docker marching for Enoch Powell in the 1970s.

A week later I was back outside Tesco. The LSA were there too — still maintain- ing a united front, which surprised me. Their drawn, hollowed-out cheeks suggest- ed it had been a long week of bitter nego- tiation. It must be tough keeping the Ho Chi Minh caucus in broad alliance with the Leninists, the Livingstone-ites, the Allende-Castro Front and the neo- Kfinishchev Reform Association.

We set up our stall on the pavement. It consisted of a round drum with a flat table-top — exactly the kind of furniture that street-hustlers use for doing the three- card trick. 'What's the message for the vot- ers this week?' I asked a fellow activist. 'Rubbish,' he said. 'Yes, I read the leaflet, but is there anything new?' Rubbish,' he insisted and unfurled the latest propagan- da sheet. It showed a well-tailored Har- vard barrister in earnest conversation with a man holding a broom. The headline read 'Help David Lammy clean up Tottenham!' And with this cheery cry we began cam- paigning once again. In the interests of electoral honesty, however, I made a slight change to the word-order. 'Tottenham!' I sang out: 'Help David Lammy clean up!'

I noticed that the voters' stoical resigna- tion was seasoned with a dash of cynicism. One man condemned Lammy, rather quaintly, as a 'yuppie' (noun. obsol. derog. 1980s, 'rich upstart'). An ageing cockney dismissed him as 'another damn Tory'.

'What's he going to do for the people round here?' a West Indian woman demanded. I responded fluently, 'he's ulun, well, plenty. Look. Here he is talking to a road-sweeper.' I passed her a leaflet. 'They only chose him 'cos he's got a black face,' she snorted.

I asked several of these disaffected vot- ers about the general election. 'Would you consider supporting William Hague?' Invariably this was greeted with hoots of derision. When it comes to doublethink, the electors are just as dexterous as any fork-tongued politician. 'Both party lead- ers are Tories,' they seem to reason, 'but Blair is a Labour Tory whereas Hague is a Tory Tory.' Next Thursday Lammy can look forward to a landslide.

I carried on campaigning for several hours. They say it's a thanldess task but they're wrong. I found myself constantly thanking everybody. 'Have a leaflet? Thank you, madam.' Couldn't care less, sir? Much obliged, thank you.' You fall into a sort of rhythm. Along comes a shop- per, you spring like Nijinksy across the pavement, half-blocking their route with- out quite tripping them up. As they try to dodge past you, you cram a leaflet into their hand, or into the belt of their skirt, or down the front of their blouse. Ten yards further down the road they fling it aside and it flutters earthwards, landing fortu- itously in the gutter with 'Clean up Totten- ham' displayed so that other passers-by `So, what are his views on modified jeans?' may reflect upon its resonant diction and far-reaching socio-political implications.

I cycled homewards up Stamford Hill and passed a site where a complex of flats and hotels was being constructed. I paused, wondering if one of these new buildings might make an appropriate memorial to Tottenham's fallen champion. Grant bodge perhaps? Trusthouse Barmy? The Bloody Good Hideaway. Or maybe just the Bernie Inn.

Previous page

Previous page