ARTS

Exhibitions 1

Exhibiting the Revolution

Celina Fox

It is inevitable that every major anniversary gives rise to a plethora of publications, from rehashes of old works to reassessments based on fresh research. But only comparatively recently has it been deemed necessary to mark such occasions with commemorative exhibitions. To what effect? If few individuals have led lives which are visually scintillating over and above the residual charm of their relics, how much more difficult is it to invest the complexities and abstractions of a whole period with three-dimensional meaning. What have any of the shows organised this year on the French Revolution conveyed which could not better be communicated in book form? Is it possible to advance beyond the predictable tableaux of Marie Antoinette, the guillotine and Marat in his bath?

Certainly as far as the major exhibition in Paris was concerned, the answer is very little. Stuffed into two wings on two floors of the Grand Palais, bolstered by vast quantities of exhibits and a staggeringly heavy catalogue which are the sine qua non of any Council of Europe show, La Revolution Francaise et L'Europe 1789- 1799 (until 26 June) possesses neither coherent argument nor the imaginative installation necessary to effect any trans- formation in our understanding. Its first section, which attempts to present Europe on the eve of the Revolution, no less, stubbornly remains a patchy assemblage of things — from paintings to ploughshares whose individual interest is diminished rather than enhanced in the mass. As for its coverage of the Revolution, few works compensate for the lack of narrative drive by conveying a larger metaphorical signifi- cance. But the bronze fragments — a foot, a hand, the horse's leg — from the eques- trian statue of Louis XIV which stood in the Place des Victoires until torn down in August 1790 mark the end of absolutism more vividly than any proclamation. And a wall-full of portraits of Prussian and Au- strian marshals, resplendently rigid with conservatism in their brilliant uniforms, signify the daunting forces of the counter- revolution better than any battle print. Of course David's painting of Marat breathing his last has the impact of great art, but . otherwise the creative output of the Re- volution, on the evidence of an endless parade of neo-classical posturing in the cause of republican virtue, is distinctly tedious. Perhaps we must wait until July for spectacular recreations of the Festival of the Supreme Being and the David exhibition at the Louvre in the autumn.

Elsewhere in Paris, those exhibitions worked best that were devoted to a single theme: satirical prints at the Bibliotheque Nationale and costumes at the Palais Gal- liera on open display, enabling Parisian matrons to finger the fichus with clucks of approval. For reasons best confined to the corridors of French museological power, the Musee Carnavalet saw fit to lend some of its finest works to the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge rather than the Grand Palais. Under the catch-all title of Paris, City of Revolution, this exhibition did not have much internal logic other than a loose narrative thread, but it contained many fascinating drawings: among them, Prieur's exquisite series en grisaille depict- ing major revolutionary events and Wille's haunting sketch of a wild-eyed Danton, crazed yet defiant as he was trundled to the guillotine. There were also some piquant curiosities: a decimal dial bracket clock from the Fitzwilliam's own collection, a pair of guillotine drop earrings complete with dangling heads and a selection of extraordinary Emett-like toy guillotines, constructed out of bone by Napoleonic prisoners-of-war at their Norman Cross depot.

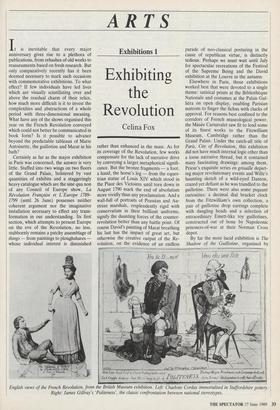

By far the most lucid exhibition is The Shadow of the Guillotine, organised by English views of the French Revolution, from the British Museum exhibition. Left: Charlotte Corday immortalised in Staffordshire pottery. Right: James Gillray's 'Politeness', the classic confrontation between national stereotypes. Professor David Bindman at the British Museum (until 10 September). Its theme is the British response to the Revolution and, in contrast to the other shows, here the status of the visual evidence is evaluated with regard to the representational conven- tions of the day and the attitudes of those who produced it. The early British reaction would have done credit to Lord Young's Enterprise Initiative, with Wedgwood manufacturing portrait medallions of re- volutionary leaders and Birmingham sup- plying designs for commode handles incor- porating revolutionary motifs. But as the violence grew, trade petered out and the traditional stereotypes of effete French- men darkened. Now we can see Gillray in context, at the height of his powers, his savage depictions of blood-crazed sans- culottes verging on the psychotic, his mas- sed hoards of bonnets rouges turning a lurid pink in the Museum's superbly col- oured prints.

Through a range of objects and images, we can trace how the legend of the Bastille was disseminated, Louis XVI achieved the status of a martyr and Charlotte Corday was immortalised in Staffordshire pottery. Moreover, the events in France are keyed into politics at home: the vilification of Fox as a sans-culotte and the propaganda efforts of the Crown and Anchor society on the one hand, the activities of the London Corresponding Society and subversive trade in Spence tokens on the other. In the end, despite the limited means at its disposal and without the benefit of public relations advisers, the government demon- strated an impressive ability to manipulate the media to its advantage.

Admittedly, it helped to have Madame Tussaud orchestrating the shock-horror factor, though Professor Bindman scotches the story that she was forced to take the casts in order to save her own neck: the heads on display were probably made during the Directory. No such academic scruples have constrained the organisers of The Tale of Two Cities exhibition (at the Corn Exchange, Brighton until 1 July and the Royal Horticultural Society Hall, Vin- cent Square, London SW1, 24 July-15 September). This slovenly show seems unable to decide which century it is dealing with, let alone for whom it is intended. It juxtaposes Dickens's chair and desk with Granada's costumes for the latest screen- ing of the novel, fake crown jewels with real court Sevres, a crude mock-up of Louis XIV's hall of mirrors at Versailles and a series of talking heads — Arthur Young, Marie Antoinette with Austrian accent, George III, a grinning eye-rolling Prince of Wales and Robespierre addressing us, as it were, from their age to ours. Perhaps this is what the GCSE history syllabus means by empathy. There is indeed a full-scale guillotine scene for all to join in, but as the lights go out before the head drops off, I would not bother to take the children.

Previous page

Previous page