GLEANINGS.

Barrisu CAVALRY.—It is strange, that eager as we are to avail ourselves of foreign fashious in our uniforms and equipments, we so often miss the point of utility. The hussar cap, for example, is, according to the real Hun- garian form, an useful thing; elle long triangular flap, which hangs down like a jelly-bag, consists of a double slip of cloth, which will fold round the soldier's face, and form a comfortable night-cap ; but, in our service, one single slip is left to flap and dangle about the man's head, no great ornament by day, and totally useless by night. The hussar pelisse also, in its original form, was intended for a rational outside covering, but with us it is a mere appendage to the soldier's neck, which, on such occasions, seems but to per- form the service of a clothes-peg. The British cavalry are certainly better provided both with personnel and zerderie/ then any cavalry. in Europe, per- haps than any cavalry in the world but they are deficient in mobility,—not in direct movernent,—for our horses have, probably, greater speed than any foreign cavalry,—but in that facility of marneuvre which enables large masses of cavalry to appear suddenly on that point in the field of battle where their assistance is required. It is in this locomotive property that the German cavalry so much excel us ; they are also better officered, more watchful, more accustomed to act independently, and, therefore, better adapted for those peculiar operations of cavalry which come under the head of field service, or outpost duty. The leading quality of an English soldier, whether horse or foot, is resistance, tile second is direct attack, and the operations of a skir- misher, or hussar, are entirely foreign to his natural propensities. The Duke of Wellington was well aware of this striking feature in the national character, and always reserved his English troops for regular battles, leaving the princi- pal duty of the outposts to the light troops of his allies.—Foreign Review.

THE ACE OF Sr. PAUL AND THE AGE OF LUTHER.—What St. Paid was to the first century, Luther was to the sixteenth. The Apostolic age has yet had no second, and no similar. The magnificent fabric of the Roman empire, the mightiest ever raised by man, was at its height. The arts of war and government, the finer embellishments of genius and taste, volumes from which even modern refinement still draws its finest delights, works of art that will serve as models of excellence and beauty to the latest hours of the world, the finest developments of the human mind in eloquence and philosophy, were the external illustrations of the first age. The moral empire was more magnificent still. The dissonant habits, feelings, and prejudices of a host of nations, separated by half the world, and yet more widely separated by long hostility and barbarian prejudices, were controlled into one vast.system of submission ; peace was planted in the midst of furious communities, agricul- ture reclaimed the wilderness, commerce covered the ocean and peopled its shores. Knowledge unforced, and thus the more productive and the more secure, was gradually making its way through the extremities of the great dominion ; intellectual light spreading, not with the hazardous and startling fierceness of a conflagration, but with the gentle and cheering growth of dawn, over every people. But the more magnificent characteristic still, was Christianity; the diffusion of a new knowledge, as much more exalted, vivid, and essential, than all that had ever been wrought out by the faculties of man, as the throne from which ittlescended was loftier than the cradle and the tomb ; the transmission of new powers over nature and mind, over the resistance of jealous prejudices and furious tyranny, and over that more mys- terious and more terrible strength that in the rulers of darkness wars against the human soul. And above all glory and honour, the presence of that Im- manuel, that being whom it is guilt lightly to name, that King of Kings whom the Heaven and the Heaven of Heavens cannot contain—God the Son, descending, on earth to take upon him our nature, and, by a love sur- passing all imagination, submitting to a death of pain and ignominy, that by his sacrifice he [night place us in a capacity to be forgiven by the justice of the Eternal. The glories of that age, throw all that follow into utter eclipse. Yet the age of Luther and the Reformation bear such resemblance as the noblest crisis of human events and human agency may bear remotely to the visible acting of Providence. The empire of Charles the Fifth, only see cond to the Roman, was just consolidated. A singular passion for literature was spreading. Government was gradually refining from the fierce turbu- lence of the Gothic nations, and the headlong tyranny of feudal princes. The fine arts were springing into a new splendour. The power of the sword was on the verge of sinking under the power of the pen. Commerce was uniting the ends of the earth by the ties of mutual interest, stronger than the old fetters of Rome. A new and singular science, diplomacy, was rising to fill up the place of the broken unity of Roman dominion, and make remote na- tions feel their importance to each other's security. The New World was opened to supply the exhausted ardour of the European mind with the stimu- lus of discovery, and, perhaps, for the more important purpose of supplying, in the precious metals, a new means of that commercial spirit which was ob- viously destined to be the regenerator of Europe. Force was the master and the impulse of the Ancient World. Mutual interest was to be the master and the impulse of a world appointed to be urged through a nobler and more salutary cal eer. To crown all, arose that art of arts, by which knowledge is preserved, propagated, and perpetuated; by which the wisdom of every age is accumulated for the present, and transmitted to the future ; by which a single mind, in whatever obscurity, may speak to the universe, and make its wrong, its wisdom, and its discuvery, the feeling and the possession of all; —that only less than miracle, the art of printing.—Blachwood's Magazine.

MisirsnY BABOONS AT TIIE CAPE.—On the hills between Simmon's Town and Muisenbourg, whole reeiments of baboons assemble, for which this station is particularly famous. They stand six feet high, and in features and manners approach nearer to the human species than any other quadruped I have ever seen. These rascals, who are most abominable thieves, used to annoy us ex- ceedingly. Our barracks were under the hills, and when we went to parade, we were invariably obliged to leave armed men for the protection of our property; and, even in spite of this, they have frequently stolen our blankets and great coats, or anything else they could lay their claws on. A poor woman, a soldier's wife, had washed her blanket and hung it out to dry, when some of these miscreants, who were ever on the watch, stole it, and ran off with it into the hills, which are high and woody. This drew upon them the indignation of the regiment, and we formed a strong party, armed with sticks and stones, to attack them, with the view of recovering the property, and inflicting such chastisement as might be a warning to them for the future. I was on the advance, with about twenty men, and I made a detour to cut them off from caverns to which they always flew for shelter. They observed my movement, and immediately detached about fifty to guard the entrance, while the others kept their post, and we could distinctly see them collecting large stones and other missiles. One old grey-headed one, in particular, who often paid us a visit at the barracks, and was known by the name of Father Murphy, MS seen distributing his orders, and planning the attack, with the judgment of one of our best generals. Finding that my design was defeated, I joined the corps de main, and rushed on to the attack, when a scream from Father Murphy was a signal for the general encounter, and the host of baboons under his command rolled down enormous Stones upon us, so that we were obliged to give up the contest, or some of us must inevitably have been killed. They actually followed us to our very doors, shouting in indication of vic- tory; and, during the whole night. we heard dreadful yells and screaming; so much so, that we expected a night attack. In the morning, however, we found that all this rioting had been created by disputes about the division of the blanket, for we saw eight or ten of them with pieces of it on their backs, as old women wear their cloaks. Amongst the number strutted Father Murphy. These rascals annoyed us day and night, and we dared not venture out unless a party of five or six went together. One morning, Father Mur- phy had the consummate impudence to walk straight into the grenadier bar- racks, and he was in the very act of purloining a serjeant's regimental coat, when a corporal's guard (which had just been relieved) took the liberty of stopping the gentleman at the door, and secured him. He was a most power- ful brute, and, I am persuaded, too much for any single man. Notwithstand- ing his frequent misdemeanors, we did not like to kill the poor creature ; so, having first taken the precaution of muzzling him, we determined on shaving his head and face, and then turning him loose. To this ceremony, strange to say, he submitted very quietly ; and, when shaved, was really an exceedingly good-looking fellow, and I have seen many a " blood " in Bond-street not half so prepossessing in his appearance. We then started him up the hill, though he seemed rather reluctant to leave us. Some of his companions came down to meet him ; but, from the alteration which shaving his head and face had made in him, they did not know him again, and, accord- ingly, pelted him with stones, and beat him with sticks, in so unmerciful a manner, that poor Father Murphy actually sought protection from his ene- mies, and he in time became quite domesticated and tame. There are many now alive, in his Majesty's 22d regiment of foot, who can vouchfor the truth of this anecdote.—Jo/in Shipp's Military Memoirs, vol. i.

ANTIQUITY OP RHYMES.—Rhymes, it will be said, are a remnant of monk- ish stupidity, an innovation upon the poetry of the ancients. They are bu indifferently acquainted with antiquity who make this assertion. Rhymes are probably of older date than either the Greek or Latin dactyl or sponde 41." —This opinion of Goldsmith is not so paradoxical as it may at first sight ap- pear: the most ancient poetry with which we are acquainted occurs in the Old Testament ; and the Hebrew poets, as many learned writers aver, em- ploy that recurrence of similar sounds which we denominate rhyme. The same form of composition seems to have been extensively cultivated by the Eastern nations, by the Arabians and Persians, and even by the Hindus, Chinese, and Tartars ; nor has it been neglected by the ruder people of Africa and America. We may even venture to affirm that the ancient classics did not altogether despise this species of embellishment. Rhymes may undoubt- edly be produced by accidental, as well as intentional combinations ; and in a language which abounds with words of similar terminations, it must often be difficult to avoid them. But an occasional recurrence of the same sound is enumerated by the ancient rhetoricians, and even by Aristotle himself, among the graces of oratorical composition ; and an ancient biographer of Homer has particularized the admission of rhyming verses as one of the various merits of his poetry.—Foreign Review.

* Goldsmith's Lond. 1759Enquiry into the present State of Polite Learning in Europe, p. 151 , 8vo.

PHYSIOLOGY OF THE EAR.—The manner in which hearing takes place may be thus simply explained—the rays emanating from a sonorous body are directed to the ear, where they become concentrated ; and in this concen- trated state they pass along the external auditory foramen to the membrane tympani, on which they excite a vibration; this vibration of the tympanum is communicated to the malleus, in immediate contact with if, the actidn of the malleus conveys them to the incus, and the latter again to the os orbiculare, whence they next reach the stapes. The basis of this last bone is extended within the vestibulum, in that part where, placed as a centre, it faces the common channel of the membranous semicircular canals, as well as the orifice- of die scala vestibuli: in consequence of this situation, the vibrations on the- stapes are extended to the water of the labyrinth, and the undulations directed, from this part, strike first the alveus communis, and are next extendedi througbout the liquor of the labyrinth surrounding the membranous semicir- cular canals, agitating by their undulations their whole surface, and this of course affects the nervous expansion spreading over all these parts. One scale of the cochlea opens into the vestibulum, amid the other begins from the fence- Ira ovalis; and being both filled with the water of the labyrinth, and commu- nicating with each other at the apex of the cochlea, the sonorous vibrations are in this manner communicated also to the scale of the cochlea ; besides this, between the scale of the cochlea, in a middle point is placed the zone moats, where the nerve is also extended and the sonorous undulations take place. It is by these varied actions of the different parts on the auditory acres that the latter is enabled to convey the vibrations to the mind.—Prom Mr. Curtis' Leetare on the Ear delivered at the Royal Institution of Great Britain.

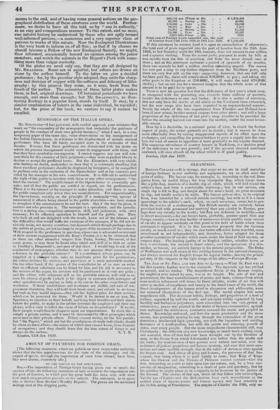

Previous page

Previous page