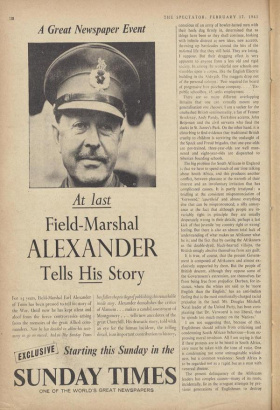

in L

hasfallen the privilege of publishing this remarkable inside story. Alexander demolishes the critics of Alamein . . . makes a candid assessment of Montgomery . . . tells new anecdotes_ of the great Churchill. His dramatic story, told with an eye for the human incident, the telling detail, is an important contribution to history. The big problem for South Africans in England is that we have to spend much of our time talking about South Africa, and this produces another conflict, between pleasure at the warmth of their interest and an involuntary irritation that has complicated causes. It is partly irrational : a bridling at the consistent mispronunciation of 'Verwoerd,' apartheid' and almost everything else that can be mispronounced; a silly annoy- ance at the fact that although people are in- variably right in principle they are usually desperately wrong in their details; perhaps a last kick of that juvenile 'my country right or wrong' feeling. But there is also an almost total lack of understanding of what makes an Afrikaner what he is; and the fact that by casting the Afrikaners as the double-dyed, black-hearted villains, the British smugly absolve themselves froin any guilt.

It is true, of course, that the present Govern- ment is composed of Afrikaners and almost ex- clusively supported by them. But the people of British descent, although they oppose some of the Government's extremism, are themselves far from being free from prejudice. Durban, for in- stance, where the whites are said to be 'more English than the English,' has an anti-Indian feeling that is the most emotionally-charged racial prejudice in the land. Mr. Douglas Mitchell, Natal leader of the United Party, has been com- plaining that Dr. Verwoerd is too liberal, that he spends too much money on the 'Natives.'

I am not suggesting that, because of . this, Englishmen should refrain from criticising and choreographed by Czechoslovakia's leading choreographer, Jiri Nemecek, for all its clumsy gimmicks, does show the latent powers of this technique to enrich aspects of the lyric theatre.

Nemecek himself is already considering using the 'magic lantern' in a production of Martinu's fantasy ballet, Spalicek, and I can imagine that it might (just might) be e)Tective in a number of operas and ballets. Think of Das Rheingold with a bridge fit for a celestial motorway thrown over to Valhalla. think of Macbeth or Les Troyens. think of The Sleeping Beauty or Giselle, think of a Swan Lake that deluged into the flood rchaikovsk himself demanded. Such devices might have to be used with non-realistic tact— there must be no reminiscence of that captive patch of frozen cloud that still tattily circles a few unimaginative cycloramas. But cinematic scenery designed within the style of the produc- tion could be quite different. Then imagine a ballet by MacMillan or Robbins set against a moving abstract continuum designed by Georgiadis or Ben Shahn. A somewhat similar technique might make a problematical modern opera, such as Erwartung, perfectly practicable on the stage. The idea is worth thinking about, perhaps even to the point of experiment.

galoshes. What could have been a contemporary cautionary talc with real satirical kick, and a straight eye on the nastiness of 'idealism' used for self-interest turns out tame, soft-centred, flabby.

0 the galoshes of flat-footed direction! What arc you to do about them but sigh and change the metaphor and go to a higher tide-mark (as I did), like Antonioni, now showing at the National Film Theatre and, one hopes, soon to be seen more widely? There's confusion of character, if you like, shifts and ambiguities, and often (as in 11 Grido particularly) a sighing, foggy atmo- sphere, a determination to have an eternal misty drizzle for one's weather, whether for outward or spiritual events; yet every moment and move- ment showing what was behind moment and movement, who thought of it so, who shaped the wide, flat landscapes and conjured up the mist.

Antonioni addicts I'm certain are born, not made; instinctively you respond or don't to his language and manner, in the widest sense his style; 'and style after all,' I read the other day, and it strikes me as hitting an elusive nail with perfect accuracy on the head, 'is not alone how one says things, but how one conceives them.' His gaps and ambiguities, his dislike of explana- tion and plain sailing, his circuitous anti-realism, yet his anti-romantic preoccupation with the fluidity and formlessness of human feeling, especially loyalty and love: these irritate some as much as they fascinate others (among the others, me). But, through the half-light and the uncer- tainties, he, as director, never falters; and never for a moment do you lose track of the central meaning, never does the action (you feel) get

Snuffed Out

By ISABEL QUIGLY

rI

beyond him. You may not see what he means all the time, as in VA vventura, a fierce argument over whose meaning here or there may suddenly arise; but you never feel that he (or come to that they, the characters) doesn't know, can't cope with, or can't in the long run convey it. Between the inconsistencies of Antonioni people and the incredibility of Johnny there's all the difference between their two directors. THE man is too great, the memories involved too vivid and sublime, for The Valiant Years, based on Sir Winston Chur- chill's war memoirs, and produced by Jack Le Vien, to be judged by any but the most exacting standards. There is a sense in which any film on this subject is bound to make an impact—for who can be unmoved by the speeches, and by bombed Rotterdam and the Dunkirk beaches?

Television

Homogenised History

- By PETER FORSTER

Previous page

Previous page