FINANCIAL SPECIAL

Putting Mr Lawson in perspective

TIM CONGDON

The last few years have seen a remark- able boom in private-sector credit. But there has been little discussion of how the recent boom compares with previous periods of rapidly increasing credit. Unless we do this, we will fail to achieve a sense of perspective on Mr Lawson's years as Chan- cellor of the Exchequer.

In doing this, I am following up an article, 'Mr Lawson's secret inflation', which I wrote for The Spectator of 27 June 1987. In that article I argued that 'the growth of credit and money is too high, the economy is expanding too quickly and interest rates are too low to prevent the return of inflationary pressures'. It all seems rather obvious in retrospect, but at the time the article caused some con- troversy.

In the 1987 article I showed that in real terms the amount of bank lending in 1986 was about 25 per cent higher than during the Barber boom of 1972 and 1973, while the increase in building society lending (again in real terms) was even larger. The contrast with the Barber boom was deliber- ate and perhaps rather unsubtle.

The Barber episode had, and retains, a notorious place in the development of modern Conservatism. The wildly exces- sive rates of monetary expansion recorded while Mr (later Lord) Barber was Chancel- lor were widely regarded as the main cause of the sharp rise in inflation in the 1970s. It became accepted that rapid monetary growth was the height of macroeconomic folly. The focus on money supply targets as the key to inflation control in the early years of the Thatcher Government is best understood as a reaction to the events of 1972 and 1973.

Mr Lawson had been particularly articu- late about the merits of monetary control, both as a backbench MP in the late 1970s and as a Treasury minister between 1979 and 1981. By showing that in 1986 lending was higher in real terms than during the Barber boom, the 1987 article warned that Mr Lawson was less committed to monet- ary restraint than he claimed to be and that there was a serious danger the mistakes of the early 1970s would be repeated. If one wanted to be dramatic, the message was that the so-called 'monetarist' policies of the early Thatcher years were about to be betrayed.

Although this interpretation of events is far from uncontroversial, it was clear by late 1988 that something had gone badly wrong. Inflation and the external payments deficit were rising far more than expected. The Government denied that the abandon- ment of broad money targets, which had been the centrepiece of financial policy in its original monetarist phase, was the source of all the trouble. But even Mr Lawson conceded that credit mattered. In rejecting criticism of the £4 billion tax cuts in the 1988 Budget, he highlighted the role of £40 billion of credit to the personal sector in stimulating consumer spending.

For all those who think that credit does indeed matter, it is important to check how it has behaved in the last two years. Has the growth of lending slowed down since mid-1987? Has the move to high interest rates started to do its work of restraining credit?

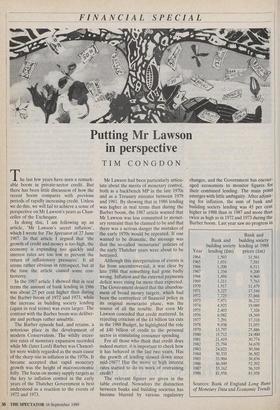

The relevant figures are given in the table overleaf. Nowadays the distinction between banks and building societies has become blurred by various regulatory

changes, and the Government has encour- aged economists to monitor figures for their combined lending. The main point emerges with little ambiguity. After adjust- ing for inflation, the sum of bank and building society lending was 45 per cent higher in 1988 than in 1987 and more than twice as high as in 1972 and 1973 during the Barber boom. Last year saw no progress in

Year Bank and building society lending (£m) Bank and building society lending at 1988 prices (£m) 1964 1,503 11,561 1965 1,031 7,581 1966 1,200 8,511 1967 1,334 9,200 1968 1,494 9,960 1969 1,211 7,763 1970 1,917 11,479 1971 3,227 17,349 1972 7,725 37,868 1973 7,971 36,232 1974 4,925 19,089 1975 2,403 7,326 1976 6,982 18,569 1977 7,291 17,318 1978 9,938 21,055 1979 13,797 25,886 1980 15,712 24,900 1981 21,419 30,774 1982 25,794 34,670 1983 24,025 30,566 1984 30,333 36,502 1985 33,904 38,836 1986 46,949 52,392 1987 53,162 56,519 1988 81,958 81,958

Sources: Bank of England Long Runs of Monetary Data and Economic Trends

FINANCIAL SPECIAL

bringing credit growth under control. On the contrary, credit growth accelerated and the comparison with the Barber years became even less flattering. The figures in the table relate to the change in the level of bank and building society lending, not to the level itself.

The first half of 1989 has been better in one respect. Lending to the personal sector is no longer growing at the extraordinarily fast rates recorded in 1987 and 1988. Indeed, mortgage advances will actually be lower this year than last, which suggests that at least the demand for housing finance is responding in the right way to higher interest rates.

However, mortgages and personal- sector credit are only part of the story. Companies have now replaced persons as the largest borrowers in the economy. In fact, corporate loan demand has increased by more than mortgages have declined, and lending to the private sector as a whole will rise once more this year. The likely outturn is about £90 billion, which will again be more than twice as high in real terms as in the Barber boom.

The recent and continuing credit boom bears comparison with the Barber boom not only in terms of scale, but also in terms of its character. Now, as then, lending to finance the acquisition and development of property has increased more quickly than other kinds of lending. Whereas in the year to May 1989, the total of all lending increased by 28.1 per cent, the amount of lending to the property sector went up by 61.1 per cent. In a recent issue of the Lloyds Bank Economic Bulletin Mr Christ- opher Johnson, the bank's chief economic adviser, remarked — with some restraint — that, 'even if the banks were not over-exposed to property two years ago, there is more a case for saying that they are over-exposed today'. Despite the jump in interest rates last summer and the persistence of base rates above 12 per cent for over a year, the credit boom has not come to an end. Lending growth has started to slow down in certain regions and for certain kinds of borrower. But the overall lending totals are still growing faster than ever. There will have to be a protracted period of financial adjustment in the early 1990s after the Lawson boom, just as there was in the mid-1970s after the Barber boom.

Tim Congdon is economic adviser to Ger- rard & National Holdings plc.

Previous page

Previous page