SWAPO SHOPPED

Elizabeth Endycott on

the atrocities carried out by an organisation the churches love

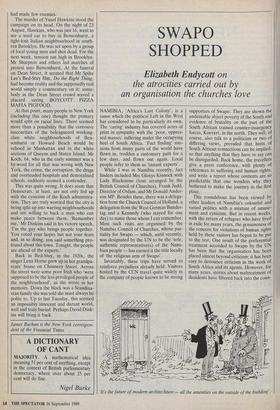

NAMIBIA, 'Africa's Last Colony', is a cause which the political Left in the West has considered to be particularly its own. The 'caring' industry has covered acres of print in sympathy with the 'poor, oppres- sed masses' suffering under the occupying heel of South Africa. 'Fact finding' mis- sions from many parts of the world have flown in, trodden a customary path for a few days, and flown out again. Local people refer to them as 'instant experts'.

While I was in Namibia recently, fact ' finders included Mrs Glenys Kinnock with Lady Blackstone (tour arranged by the British Council of Churches), Frank Judd, Director of Oxfam, and Mr Donald Ander- son MP. Besides these, there was a delega- tion from the Church Council of Holland, a delegation from the West German Bundes- tag and a Kennedy (who stayed for one day) to name those whom I can remember. Most such visits are organised by the Namibia Council of Churches, whose par- tiality for Swapo — which, until recently, was designated by the UN to be the 'sole, authentic representative(s) of the Nami- bian people — has earned it the title locally of 'the religious arm of Swapo'.

Invariably, these trips have served to reinforce prejudices already held. Visitors hosted by the CCN travel quite widely in the company of people known to be strong

supporters of Swapo. They are shown the undeniable abject poverty of the South and evidence of brutality on the part of the South African trained counter-insurgency forces, Koevert, in the north. They will, of course, also talk to a politician or two of differing views, provided that hints of South African connections can be implied. so that anything that they have to say can be disregarded. Back home, the travellers give a press conference, with plenty of references to suffering and human rights, and write a report whose contents are so predictable that one wonders why they bothered to make the journey in the first place.

This roundabout has been viewed by other leaders of Namibia's colourful and varied politics with a mixture of amuse- ment and cynicism. But in recent weeks, with the return of refugees who have lived in exile for many years, the genuineness of the concern for violations of human rights held by these visitors has begun to be put to the test. One result of the preferential treatment accorded to Swapo by the UN has been that the organisation has been placed almost beyond criticism; it has been easy to denounce criticism as the work of South Africa and its agents. However, for many years, stories about maltreatment of dissidents have filtered back into the coun- 'It's the future of modern architechture — all the amenities on the outside of the building'. try, and, in 1985, a 'Parents' Committee' was formed to publicise the concern of families who had members who had gone to join Swapo in exile and had not been heard of for many years. The committee soon became the target of denunciatory remarks from organisations which sup- ported Swapo, while petitions to the UN and to the three Namibian churches whose support for Swapo was exclusive (the Roman Catholics, the Lutherans and the Anglicans) were ignored. Even the parent churches in Europe, who listened only to their people in Namibia, seemed to regard attempts to draw their attention to the concern of the parents as acts of affrontery. The parrot cry has been: 'The Churches support Swapo, therefore Swapo is a Christian organisation.'

Now, with the United Nations installed in Namibia and the implementation of Resolution 435 under way, the refugees are returning, and the full horror of what has gone on is coming to light. One of the victims, who had been a devoted Swapo activist before going into exile to be free from constant harassment by the South African police, worked at the organisa- tion's headquarters in Angola as a youth leader, and also took his turn as a fighter in the guerrilla army. Then on 2 September 1984 he was arrested by Swapo security and accused of being a South African spy. 'I was taken to a detention centre known as Kilimanjaro, about 170km north of the Namibian border, where I was stripped and had all possessions taken from me,' he told me. 'I was beaten for about four hours by guards who tried to make me confess that I had been sent to infiltrate the leadership. After some days of being beaten whenever the guards felt like it, I was taken to Lubango and put into a hole in the ground. I had to live there until 10 April, when we were all released.'

The holes, where so many dissidents were held, are room-sized pits, often dug by the prisoners themselves, covered with corrugated iron and scrub so that they cannot easily be seen, even from quite a short distance. Swapo never permitted the Red Cross to inspect their refugee camps, but when representatives of the Lutheran Church visited Lubango and were shown that the normal prison was empty, they went away satisfied that Swapo was not holding political prisoners. The pits held as many as 36 people dressed only in singlet and underpants, which were never washed or changed. Tins were provided for lava- tories and every morning prisoners had to climb a vertical ladder to empty them; otherwise they never saw the light. They were allowed to wash face and hands perhaps once in three months. Water was the only drink, and food consisted of rice or `mealies', cooked without sugar or salt and served in a communal bowl. Beatings were frequent, especially when the guards were drunk; many prisoners went mad, were taken away and never seen again. Deaths from TB, beri-beri and other dis- eases related to malnutrition were fre- quent. Usually some of the prisoners had to take the body of their companion out and bury it, then return to the hole. Medical care was non-existent.

Some people now returning have sur- vived as long as nine years in these conditions. One woman, now only 22, was abducted from her school when she was 14 and, because she refused the sexual adv- ances of her captors, was accused of being a spy and thrown into a pit. Women and girls were frequently taken out and raped; children were born in the pits (no medical attention was given). Miraculously, some even survived.

Even girls who did not live in the pits were often raped by guards of Swapo officials. I met a woman, now only 26 years old, who left Namibia when she was 16 looking for education and a better life, who has had six children in ten years. She has no idea where any of them is. Swapo policy has been to separate families of ordinary refugees, and I met many men who had not seen their wives and children for many years. Older children were sent to other African countries, or to East Germany or Cuba, for 'education', while younger ones were sent to Tobias Hainyeko camp in Angola. Children born as a result of rape were taken from their mothers at a very young age and taken to the same camp, where their names were changed and they lived until they, too, were old enough to be sent away for 'education'.

But despite all this, support for Swapo from the churches — and from the Labour Party — is unwavering. I understand that Mrs Kinnock and Lady Blackstone were told about these things and said they would 'take up the matter with Swapo', but they did not meet any of the victims. And not they, nor Frank Judd, nor Donald Ander- son have mentioned anything of it in their various press conferences held to report the results of their 'fact-finding'.

In May of this year, the Anti-Apartheid 'I love a when she dominates' Movement launched a 'Swapo Election Campaign Appeal', sponsored by the Re- verend Trevor Huddlestone, Neil Kin- nock , David Owen, Paddy Ashdown and Norman Willis, while, to coincide with 'Namibia Day' on 26 August, the Irish Anti-Apartheid movement brought out 'Swapo Solidarity Bonds', costing £5 each.

It seems that some human rights are less humane than others.

Previous page

Previous page