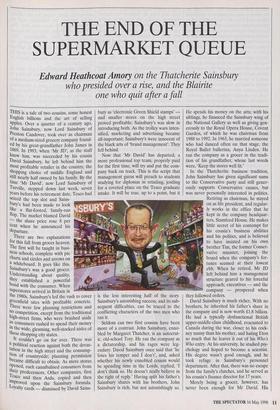

THE END OF THE SUPERMARKET QUEUE

Edward Heathcoat Amory on the Thatcherite Sainsbury

who presided over a rise, and the Blairite one who quit after a fall

THIS is a tale of two cousins, some honest English billions and the art of selling apples. Over a quarter of a century ago, John Sainsbury, now Lord Sainsbury of Preston Candover, took over as chairman of a medium-sized grocery company found- ed by his great-grandfather John James in 1869. In 1993, when 'Mr JD', as the staff knew him, was succeeded by his cousin David Sainsbury, he left behind him the most profitable retailer in the country, the shopping choice of middle England and still nearly half owned by his family. By the time 'Mr David', now Lord Sainsbury of Turville, stepped down last week, seven Years before his retirement date, Tesco had seized the top slot and Sains- bury's had been made to look like a flat-footed, family-run flop. The market blamed David — the share price rose 8 per cent when he announced his departure.

It couldn't go on for ever. There was a Political reaction against both the devas- tation in the high street and the consump- tion of countryside; planning permission became difficult to obtain. As more stores opened, each cannibalised consumers from their predecessors. Other companies, first Tesco and then Asda, copied and then unproved upon the Sainsbury formula. LoYalty cards — dismissed by David Sains- bury as 'electronic Green Shield stamps' and smaller stores on the high street proved profitable; Sainsbury's was slow in introducing both. As the trolley wars inten- sified, marketing and advertising became all-important; Sainsbury's were innocent of the black arts of 'brand management'. They fell behind.

Now that `Mr David' has departed, a more professional top team, properly paid for the first time, will try and put the com- pany back on track. This is the script that management gurus will preach to students studying for diplomas in retailing, jostling for a coveted place on the Tesco graduate intake. It will be true, up to a point, but it is the less interesting half of the story. Sainsbury's astonishing success, and its sub- sequent difficulties, can be traced to the conflicting characters of the two men who ran it.

Seldom can two first cousins have been more of a contrast. John Sainsbury, enno- bled by Margaret Thatcher, is an autocrat- ic, old-school Tory. He ran the company as a dictatorship, and his rages were leg- endary. David Sainsbury once said that 'he loses his temper and I don't', and, asked whether his newly ennobled cousin would be spending time in the Lords, replied, `I don't think so. He doesn't really believe in the right of reply.' Having split his father's Sainsbury shares with his brothers, John Sainsbury is rich, but not astonishingly so. He spends his money on the arts; with his siblings, he financed the Sainsbury wing of the National Gallery as well as giving gen- erously to the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, of which he was chairman from 1988 to 1992. In 1963, he married someone who had danced often on that stage, the Royal Ballet ballerina, Anya Linden. He ran the company as a grocer in the tradi- tion of his grandfather, whose last words were, 'Keep the stores well lit.'

In the Thatcherite business tradition, John Sainsbury has given significant sums to the Conservative party and still gener- ously supports Conservative causes, but was never personally interested in politics. Retiring as chairman, he stayed on as life president, and regular- ly works in the office that he kept in the company headquar- ters, Stamford House. He makes little secret of his contempt for his cousin's business abilities and his politics, and is believed to have insisted on his own brother Tim, the former Conser- vative minister, joining the board when the company's for- tunes seemed at their lowest ebb. When he retired, Mr JD left behind him a management structure geared to his forceful approach; executives — and the company — prospered when they followed orders.

David Sainsbury is much richer. With no brothers, he inherited his father's share in the company and is now worth £1.8 billion. He had a typically dysfunctional British upper-middle-class childhood, evacuated to Canada during the war, closer to his cock- ney nanny than his mother, and hating Eton so much that he leaves it out of his Who's Who entry. At his university, he studied psy- chology and hoped to become a scientist. His degree wasn't good enough, and he took refuge in Sainsbury's personnel department. After that, there was no escape from the family's clutches, and he served as his cousin's finance director for 17 years.

Merely being a grocer, however, has never been enough for Mr David. His money helped found the SDP, and he remained a staunch supporter of David Owen long after all the Doctor's other adherents had drifted away. He funded the Social Market Foundation think-tank, has written pamphlets on industrial policy and is never happier than in the company of the policy `wonks'. His principal self-indul- gence is flying in overseas academics for dinner. Otherwise, he lives a modest Not- ting Hill life. One friend remarks that he's the only billionaire who admits to spending Friday nights in, watching Frasier on televi- sion. He gives huge sums of money to worthy charitable causes — technical edu- cation, plant science, disadvantaged chil- dren — mostly through his principal charitable vehicle, the Gatsby Foundation, the name a rare whimsy in a determinedly humdrum life.

Once in the top job at Sainsbury's, he wasted no time in applying his social and political principles to minding the store. Decision-taking became a consensual, con- sultative process. 'The chairman's office never imposed,' says one employee. His personal assistant says, 'I imagined that most bosses might try to force their beliefs on the staff [but] the chairman talks to one on an equal footing.' He had disapproved of his cousin's approach; now he was deter- mined to do it the social democratic way. A turquoise Chevrolet van replaced the Bent- ley in which his predecessor had toured the stores; analysis supplanted autocracy as the force that drove the business. One current employee explains: 'He brought in outside consultants to "trim the hierarchical struc- ture". Everyone was allowed to do their own thing. The scheme was called Genesis, but was soon known in the firm as Geno- cide. Morale plummeted. Managers took their eye off the competition.'

It soon became apparent that this approach was failing, but, as the company's biggest shareholder, it was some time before anybody felt able to tell him. The first pressure came from the family; at one stage the share price slump took £1.9 bil- lion off their combined fortune. Shortly afterwards, direct criticism from outside shareholders began. Mr David stepped back from management, strengthening his links with New Labour at the same time. For the last year most of the decisions have been made by Dino Adriano, the new chief executive. When a slightly better set of results was announced last week, David Sainsbury seized the opportunity to resign on a reasonably high note. Everyone, him- self included, heaved a sigh of relief. His escape route has been well planned. When Tony Blair ran for party leader, his campaign fund received a contribution from David Sainsbury. New Labour, for this rich politician manqué, is the SDP made, flesh. At the last election he con- tributed somewhere between £1 million and £2 million to the party coffers. A peer- age was his initial reward, but the collabo- ration between the billionaire and the Blairites has gone closer than that. This February, at a private dinner in his honour attended by Peter Mandelson, New Labourites praised his role in funding not their own party but the SDP, its spiritual progenitor. By some in the government he is seen as a financial John the Baptist to Tony Blair's Saviour. They have promised him a job, either in the Department of Trade and Industry or the Department of Education and Employ- ment. He will spend a year in quarantine, working on the University for Industry, and improving his voting record in the Lords, in an attempt to draw the teeth from the kind of attacks that were focused on David Simon when he went straight from BP into the government. 'David Sainsbury has a long, long political history,' says a govern- ment insider, 'and wants to spend the last few years of his life doing something worth- while.' Presumably, he has never regarded his work in the family firm as worthwhile — not uncommon in a fourth-generation billionaire, but slightly sad in a Sainsbury. None of the fifth generation wants to be a grocer, so it seems that one of Britain's most vigorous dynasties will end here. Meanwhile, we have to hope that he will help to run his country more effectively than he ran the family firm.

Previous page

Previous page