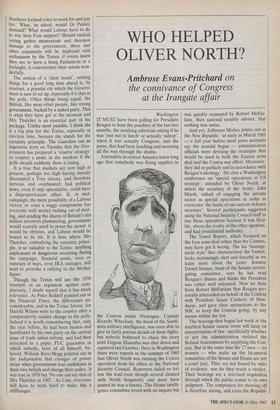

WHO HELPED OLIVER NORTH?

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard on

the connivance of Congress at the Irangate affair

Washington IT MUST have been galling for President Reagan to hear the punditry of the last two months, the mocking editorials asking if he was 'just out to lunch' or actually 'asleep', when it was actually Congress, and the press, that had been lunching and snoozing all the way through the drama.

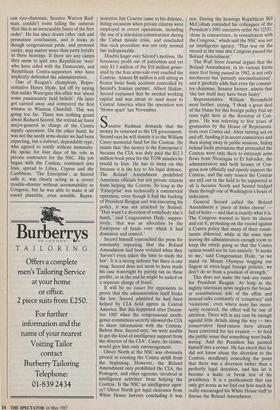

Journalists in central America knew long ago that somebody was flying supplies to the Contras inside Nicaragua. Captain Ricardo Wheelock, the head of the Sandi- nista military intelligence, was even able to give us fairly precise details of these fights, but nobody bothered to chase the story until Eugene Hasenfus was shot down and captured last October. Here in Washington there were reports in the summer of 1985 that Oliver North was running the Contra operation from his office at the National Security Council. Reporters failed to fol- low the lead even though several chatted with North frequently and must have sensed he was a fanatic. The House intelli- gence committee toyed with an inquiry but was quickly reassured by Robert McFar- lane, then national security adviser, that nothing was amiss.

And yet, Jefferson Morley points out in the New Republic, 'as early as March 1983 — a full year before most press accounts say the scandal began — administration officials were devising the strategies that would be used in both the Iranian arms deal and the Contra war effort. Moreover, they did so publicly and in accordance with Reagan's ideology.' He cites a Washington conference on 'special operations in US strategy', attended by Oliver North, at which the secretary of the Army, John Marsh, talked of engaging the private sector in special operations in order to overcome 'the limits of our current defence structure'. Several participants suggested using the National Security Council staff to run these operations because it was flexi- ble, above the rivalry of the other agencies, and had presidential authority.

The Tower Report, which focussed on the Iran arms deal rather than the Contras, may have got it wrong. The lax 'manage- ment style' that characterised the former, looks increasingly alert and forceful as we learn more about the latter. Senator Daniel Inouye, head of the Senate investi- gating committee, says he has read Reagan's diaries and thinks the President was rather well informed. Now we hear from Robert McFarlane that Reagan per- sonally interceded on behalf of the Contras with President Suazo Cordova of Hon- duras, and gave clear instructions to the NSC to keep the Contras going, by any means within the law.

The hearings that began last week in the marbled Senate caucus room will hang on interpretation of law: specificially whether or not the administration violated the Boland Amendment by supplying the Con- tras. But at the same time the 27 men — no women — who make up the bicameral committee of the Senate and House are not a court jury. They are not bound by rules of evidence, nor do they reach a verdict. Their hearings are a televised inquisition through which the public comes to its own judgment. The temptation for showing off is therefore strong, and even the Republi- can vice-chairman, Senator Warren Rud- man, couldn't resist telling the cameras `that this is an inexcusable fiasco of the first order'. He has since drawn other rash and premature conclusions, and it looks as though congressional pride, and personal vanity, may matter more than party loyalty in these hearings. If there are any camps they seem to split into Republican 'wets' who have sided with the Democrats, and Republican Contra-supporters who have implicitly defended the administration.

One of Reagan's champions, Repre- sentative Henry Hyde, led off by saying that unlike Watergate this affair was 'about some passionately held beliefs'. He later got carried away and compared the first witness to Winston Churchill. This was going too far. There was nothing grand about Richard Secord, the retired air force major-general in charge of the Contra supply operation. On the other hand, he was not the seedy arms-dealer we had been expecting, but a stalwart, dependable type, who agreed to testify without immunity. He spoke for four days of his role as private contractor for the NSC. His job began with the Contras, continued into Iran, spread to Libya, Cyprus and the Caribbean. 'The Enterprise', as Secord calls it, was clearly acting as a covert trouble-shooter without accountability to Congress, but he was able to make it all sound plausible, even sensible. Repre- sentative Jim Courter came to his defence, listing occasions when private citizens were employed in covert operations, including the use of a television commentator during the Cuban missile crisis, and concluded that such procedure was not only normal but indispensable.

Doubts linger over Secord's motives. He foreswore profit out of patriotism and yet only $3.5 million of the $18 million gener- ated by the Iran arms sale ever reached the Contras. Almost $8 million is still sitting in frozen Swiss bank accounts controlled by Secord's Iranian partner, Albert Hakim. Secord explained that he needed working capital and was about to send more to Central America when the operation was `blown apart' last November.

Senator Rudman demands that the money be returned to the US government. Secord says he will donate it to the William Casey memorial fund for the Contras. He insists that 'the money is the Enterprise's' because the CIA was duly paid the $12.3 million book price for the TOW missiles he resold to Iran. He has to insist on this because it is the key to his legal defence. The Boland Amendment prohibited American officials but not private citizens from helping the Contras. So long as the `Enterprise' was technically a commercial operation, even though it had the backing of President Reagan and was executing his policy, it was not attacked by Boland. `That wasn't a diversion of somebody else's funds,' said Congressman Hyde, suppor- tively, 'that was an allocation by the Enterprise of funds over which it had dominion and control.'

Secord himself reproached the press for constantly repeating that the Boland Amendment had been violated when they `haven't even taken the time to study the law'. It is a strong defence but there is one snag: Secord does not seem to have made his case watertight by paying tax on these profits, so in the end he might be nailed on a separate charge of fraud.

It will be no easier for opponents to prove that the administration itself broke the law. Secord admitted he had been helped by CIA field agents in Central America. But this happened after Decem- ber 1985 when the congressional intelli- gence committees secretly allowed the CIA to share information with the Contras. Before then, Secord says, 'we were unable to get the kind of intelligence support from the director of the CIA'. Casey, he claims, would give him only encouragement.

Oliver North at the NSC was obviously pivotal in creating the Contra airlift from the beginning. However, the Boland Amendment only prohibited the CIA, the Pentagon, and other agencies 'involved in intelligence activities' from helping the Contras. Is the NSC an intelligence agen- cy? Oliver North got legal clearance from White House lawyers concluding it was not. During the hearings Republican Bill McCollum reminded his colleagues of the President's 1981 executive order No 12333, `done in concurrence, in consultation with the Congress,' which said the NSC was not an intelligence agency. 'That was on the record at the time this Congress passed the Boland Amendment.'

The Wall Street Journal argues that the Boland Amendment, in its various forms since first being passed in 1982, is not only incoherent but 'patently unconstitutional', and it gleefully adds that even the commit- tee chairman, Senator Inouye, admits that `the law itself may have been faulty'.

Representative William Broomfield went further, saying, 'I think a great deal of the blame for this foreign policy foul-up rests right here at the doorstep of Con- gress.' He was referring to five years of gymnastics by the House of Representa- tives over Contra aid. After turning aid on and off, funding it in secret committees and then shying away in public sessions, hiding behind facile provisions that pretended the Contras were only there to intercept arms flows from Nicaragua to El Salvador, the administration and both houses of Con- gress now officially and openly support the Contras, and the only reason the Contras are still out in the field to be supported at all is because North and Secord bridged them through one of Washington's bouts of indecision.

General Secord called the Boland Amendment a 'piece of Swiss cheese' full of holes — and that is exactly what it is. The Congress wanted to have its cheese and eat it, protesting on the record against a Contra policy that many of their consti- tuents abhorred, while at the same time leaving the administration enough room to keep the rebels going so that the Contra option would not be lost entirely. 'It seems to me,' said Congressman Hyde, 'as we stand on Mount Olympus wagging our fingers at extra-legal foreign policies, we don't do so from a position of strength.'

This does not make the task any easier for President Reagan. As long as the nightly television news neglects the broad- er constitutional side of the affair and instead talks constantly of 'conspiracy' and `violations', even where none has neces- sarily occurred, the effect will be one of attrition. There will in any case be enough squalid little details along the way — two conservative fund-raisers have already been convicted for tax evasion — to feed the public sense that something went badly wrong. And the President has painted himself into a corner. He has sworn that he did not know about the diversion to the Contras, needlessly conceding the point that there was a diversion rather than a perfectly legal donation, and has let it become a make or break test of his presidency. It is a predicament that can only get worse as we find out how much he really encouraged his White House staff to finesse the Boland Amendment.

Previous page

Previous page