SHIVA NAIPAUL PRIZE

A BIT OF A HITCH

HUMPHRY SMITH

I WAS hitch-hiking out of Cape Town. I had gone about twenty miles, and had another thousand to go. Cape Town — called the 'mother-city' by white South Africans — is built to a human scale. Perhaps I mean a European scale. There are two-storeyed buildings. Some of the streets are curved and narrow. The city fits comfortably between the Atlantic and the majestic bulk of Table Mountain.

There is one way out, between the mountain and the sea. It leads to a messier, stranger world of townships and squatter- camps, a world that is flat, dirty and violent.

The highway lay dead straight over the huge smog-covered plain. Some miles ahead, the Paarl mountains rose abruptly. I had stood for an hour.

At last, a car pulled up. The driver got out — a fat man wearing a baby-blue sun-hat and fawn trousers. He was going to Port Elizabeth, a depressed industrial city about five hundred miles down the road.

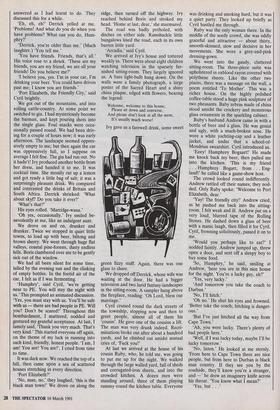

I squeezed in — there were four people already in the little white car — and off we drove. The driver's name was Cyril. Next to me sat Boris — a thickset, thick- moustached little man — and Ivy, a smiling matronly giantess. In front sat a toothless gnome called Derrick, dressed in clownish American-tourist clothes. They were all 'coloured people', as they put it (progres- THIS is the winner of the fifth Shiva Naipaul Memorial Prize. It is awarded to the entrant 'best able to describe a visit to a foreign place or people. It is not for travel wtiting in the conventional sense, but for the most acute and profound observation of cultures and scenes evidently alien to the writer.' The prize is worth £1,000.

This year's judges were Christopher Sinclair-Stevenson, Shiva Naipaul's pub- lisher; Allan Massie, the novelist; Alexander Chancellor, editor of the Independent Magazine; Dominic Lawson, editor of The Spectator, and Mark Amory, the literary editor of The Spectator.

There were 149 entries from 20 countries. The final shortlist included articles by Anne Applebaum and Mira Stout, but in the end Humphry Smith emerged as the winner by a clear margin.

sive whites call them 'so-called "Col- oureds" '; progressive Coloureds call themselves black), on a short trip home.

The so-called 'so-called "Coloureds" 'of the Cape must have the most complicated ancestry of any people on Earth. English, French, Dutch, Malay, Bushman and Xhosa blood runs in their veins. To me, a Londoner, some look like West Indians, others like Italians, Indians, Moroccans. Their mother-tongue is Afrikaans. My companions spoke English in an accent that combines the twang of Jamaica, the lilt of India, and the nasal moan of Birming- ham.

We headed up into the beautiful vine- clad slopes of the Paarl.

"Ave some beer,' said Boris. I picked up one of the half-dozen bottles rolling around my feet, and poured myself a glass, which Ivy had produced from some inner fold. Vaguely thanking the company, I took some sips.

`So, you're all going home to Port Elizabeth?'

Silence. Boris gripped my wrist.

'Finish it. Drink it, man.' I gulped down the beer and, following his mimed instruc- tions, poured the other three men a glass.

'Are you all related? Same family?'

General laughter, and chattering jokes in Afrikaans. Derrick turned round, grin- ning. His pink gums glistened.

'Oh yes, it's this. This man here is marrying my sister there, and that . . is his brother!' Everyone dissolved into wild laughter, Derrick giving his shrill cry, `Yarrrr! Yassus!'

'No, my dear, they are being silly men,' said Ivy, smiling. 'They all work together, and Cyril's my cousin.'

All the time the silent Boris kept nudg- ing me to pour out more rounds. We had got through three rounds when Cyril asked the old question: 'What do you think of South Africa?'

Beautiful, but a lot of problems, I answered as I had learnt to do. They discussed this for a while.

'Eh, eh, eh!' Derrick yelled at me. 'Problems! And what do you do when you have problems? What can you do, Hum- phry?'

'Derrick, you're older than me.' (Much laughter.) 'You tell me.'

'You have friends. Friends, that's all.' His voice rose to a shriek. 'These are my friends, you are my friend, we are all your friends! Do you believe me?'

'I believe you, yes. I'm in your car, I'm drinking your beer. You could have driven past me; I know you are friends.'

'Port Elizabeth, the Friendly City,' said Cyril brightly.

We got out of the mountains, and into rolling cattle-country. At some point we switched to gin. I had mysteriously become the barman, and kept pouring shots into the single glass. Foul snacks were occa- sionally passed round. We had been driv- ing for a couple of hours now; it was early afternoon. The landscape seemed oppres- sively empty to me; but then again the car was oppressively full, so I suppose on average I felt fine. The gin had run out. No it hadn't! Ivy produced another bottle from her dress, and handed it to me. It was cocktail time. She messily cut up a lemon and got ready a little bag of salt; it was a surprisingly pleasant drink. We compared and contrasted the drinks of Britain and South Africa. Derrick shrieked: 'What about skyf? Do you take it ever?'

'What's that?'

His eyes rolled. `Marridge-wana.'

'Oh yes, occasionally.' Ivy smiled be- nevolently at me, like an indulgent aunt.

We drove on and on, drunker and drunker. Twice we stopped in quiet little towns, to load up with beer, biltong and brown sherry. We went through huge flat valleys, coastal pine-forests, dusty endless hills. Boris clambered over me to be gently sick out of the window.

We had all been silent for some time, lulled by the evening sun and the clinking of empty bottles. In the foetid air of the car, I felt as if I was fermenting.

'Humphry', said Cyril, 'we're getting near to PE. You will stay the night with us.' This prompted an animated discussion. 'Yes, you must stay with us. You'll be safe with us — there are bad people in PE. Will you? Don't be scared!' Throughout this bombardment, I muttered, nodded and gestured my grateful acceptance. At last, I lamely said, 'Thank you very much. That's very kind.' This started everyone off again, on the theme of my luck in running into such kind, friendly, honest people. 'I am, I am! You are! You are!', I cried from time to time.

It was dark now. We reached the top of a hill, then came upon a sea of scattered houses stretching in every direction.

'Port Elizabeth?'

`No, man, no,' they laughed, 'this is the black man town!' We drove on along the ridge, then turned off the highway. Ivy reached behind Boris and stroked my head. 'Home at last, dear,' she murmured.

The road was badly potholed, with ditches on either side. Ramshackle little bungalows lined the road, each in its own barren little yard.

'Arcadia,' said Cyril.

We arrived at Ivy's house and tottered weakly in. There were about eight children watching television in the sparsely fur- nished sitting-room. They largely ignored us. A bare light-bulb hung down. On the walls were a family photograph, a large poster of the Sacred Heart and a shiny china plaque, edged with flowers, bearing the legend:

Welcome, welcome to this house; Please sit down and converse, And please don't look at all the mess, It's usually much worse!

Ivy gave us a farewell drink, some sweet green fizzy stuff. Again, there was one glass to share.

We dropped off Derrick, whose wife was waiting at the door. He had a bigger television and two lurid fantasy-landscapes in the sitting-room. A sampler hung above the fireplace, reading: 'Oh Lord, bless our marriage.'

Cyril cruised round the dark streets of the township, stopping now and then to greet people, almost all of them his 'cousin'. He gave one of the cousins a lift. The man was very drunk indeed. Recri- minations broke out after about a hundred yards, and he climbed out amidst mutual cries of, Tuck you!'

At last we arrived at the house of his cousin Ruby, who, he told me, was going to put me up for the night. We walked through the large walled yard, full of sheds and corrugated-iron sheets, and into the crowded kitchen. A dozen men were standing around, three of them playing rummy round the kitchen table. Everyone was drinking and smoking hard, but it was a quiet party. They looked up briefly as Cyril hustled me through.

Ruby was the only woman there. In the middle of the seedy crowd, she was oddly graceful and attractive — about thirty, smooth-skinned, slow and decisive in her movements. She wore a grey-and-pink dressing-gown.

We went into the gaudy, cluttered sitting-room. The three-piece suite was upholstered in oxblood rayon covered with polythene sheets. Like the other two places, there was a message on the wall, a poem entitled `To Mother'. This was a richer house. On the highly polished coffee-table stood a huge pink sculpture of two pheasants. Baby zebras made of china stood amidst the crockery and monstrous glass ornaments in the sparkling cabinet.

Ruby's husband Andrew came in with a bottle of beer and a glass. He was genial and ugly, with a much-broken nose. He wore a white yachting-cap and a leather jacket, and under that a school-of- Mondrian sweatshirt. Cyril introduced us.

'Eeey! Humphrey Bogaart!' He made me knock back my beer, then pulled me into the kitchen. 'This is my friend . . . Humphrey Bogart, from. . . Eng- land!' he called like a game-show host.

The crowd looked round indifferently. Andrew rattled off their names; they nod- ded. Only Ruby spoke: 'Welcome to Port Elizabeth, dear.'

`Yay! The friendly city!' Andrew cried, as he pushed me back into thesitting- room. I felt weak and ill. Andrew fait on a very loud, blurred tape of the Rolling Stones. He dashed down a glass of beer with a manic laugh, then filled it for Cyril. Cyril, frowning solicitously, passed it on to me.

'Would you perhaps like to eat?' I nodded faintly. Andrew jumped up, threw open a door, and sent off a sleepy boy to buy some food.

`So, Humphry,' he said, smiling at Andrew, 'here you are in this nice house for the night. You're a lucky guy, eh?'

'Yes, very lucky.'

'And tomorrow you take the coach to Durban.'

'No, I'll hitch.'

'Oh no.' He shut his eyes and frowned. 'Better take the coach; hitching is danger- ous.'

'But I've just hitched all the way from Cape Town.'

`Ah, you were lucky. There's plenty of bad people here.'

'Well, if I was lucky today, maybe I'll be lucky tomorrow.'

'No, listen.' He looked at me sternly. 'From here to Cape Town there are nice people, but from here to Durban is black man country. If they see you by the roadside, they'll know you're a stranger, and —' he drew an imaginery knife across his throat. 'You know what I mean?'

'Yes, but . . 'No, man, don't be crazy!' Andrew cried. 'The kaffirs will fucking kill you!' He went on in this vein.

'You see, Humphry, we are decent people,' said Cyril. 'With us, you are safe. But in Transkei they will steal your bag and kill you for fun. No, take the coach. It's lovely — air-conditioning, toilets, vid- eos. . . .' He smiled hopefully.

I agreed to take the coach. The food came: cold fried chicken and chips, with a freezing acidic bean stew. We ate silently. A dachshund puppy emerged, hoping for scraps; Cyril and Andrew pun- ched and kicked it till it slunk away whimpering. Ruby drifted through and pulled a little girl out of bed, to make way for me.

'How are you, my dear?' she asked. 'Fine, fine; a bit tired.' It was half-past one. My head was hammering.

'Go and have a bedtime pipe, then.'

I demurred, but Andrew was too much for me. We went outside with two or three others, and stood shivering in the rain. A tall, pale man — 'Mr Mathis' — pulled out the pipe, a jagged brown bottleneck stop- ped with a tight roll of card, and filled it. The grass was very hot and acrid. I coughed hard on it. Someone grumbled quietly to Andrew; he answered emphati- cally: 'He's not a larney [whitey], he's a foreigner.' Andrew set the company off on a series of admiring questions about London, Brit- ish music and so on. Someone fingered my shirt.. 'Oh, it's so nice . . . from overseas. I'd love a little souvenir, from overseas you know . . .

'Maybe, but I love this shirt, you know.' 'Yeah, don't bother the boy,' said Mr Mathis. He was filling the pipe again. This time he crumbled in a little white pill. 'What's that?'

`Mandrax — special treat.' This pipe was very bitter. After each drag, you had to stop and produce a combined retch and dribble. My headache drifted away; I felt heavy and comfortable. They were pleased to hear that Mandrax was just an exotic name to me. Mr Mathis started filling the pipe again. I realised I could hardly stand and said good night.

I WOKE to the sound of hoovering and hammering. It was grey and drizzling outside; a good excuse for not hitching. A huge pot of water was boiling in the kitchen. Ruby came in, wearing a smart brown suit. She called a child to make tea and butter my bread, and interrogated me about my home and family. I wanted to interrogate her, but didn't know where to start. What was this elegant woman doing in this peculiar house? Who exactly lived here? Did they have parties every night? Andrew and some of last night's crew were chatting out in the rain. With sinking heart, I saw they were grouped around a bottle of sherry. I went out to greet them. 'Bogaaart!' Andrew yelled. 'How are you, my friend?' He pulled the glass out of Boris's hand and poured me a good half- pint. I trembled slightly.

'Oh, are you cold? Let's go inside.'

By 'inside', he meant the lavatory, a narrow shack on the edge of the yard. I was given pride of place. Giant, a lanky young guy in denim shorts, perched on my knees.

In the next half hour, we became about a dozen strong. The crowd was almost gla- morously disreputable-looking, in battered caps, dirty coarse jackets with the collars up, huge muddy boots. A couple of them had no teeth. They could have been a chorus of workers from an agitprop play. Andrew, though, was in his natty gear of the day before.

A man called Stanley came with a guitar. Like Andrew, he was clearly a cut above the rest of the company. Andrew took us both to talk in the kitchen.

I gave Stanley the standard details — age, occupation, purpose of visit — then asked, 'And what do you two do?'

'We both worked in the Volkswagen factory until two years ago', said Andrew.

I nodded sympathetically. 'And you lost your jobs?'

'No, man, we gave it up. It was so boring.'

'Yes, boring. And no opportunities,' said Stanley.

`So now?'

Andrew laughed. 'We're businessmen. We sell liquor, skyf and Mandrax.'

They told me about their merry life, dodging and bribing the Port Elizabeth drug squad.

'But, you know,' said Stanley senten- tiously, 'a life of opportunity may be more fun, but it's more risky too.'

'I'm sure.'

'Yes,' said Andrew, 'we are fun people. But we are also killers!' He grinned bright- ly. 'I've stolen your socks, Bogart, and I'm doing a little black magic!' He rolled his eyes.

'He's only joking,' Stanley explained to me. 'But seriously, you should watch out if you do lose a thing. There's a lot of— you know — witches here. It's no joke, man. Now my cousin — I saw this with my own eyes — she'd been cursed, and she was going to have a baby, but instead, out of her thing there came this biiig, gigantic cockroach! I saw it! But don't worry; we're all Christians here.'

'Oh good.'

'Yes, our church is the Apostolic Church.'

'What's that?'

'You don't know it?' said Andrew in dismay. 'But we're big; we're from Ger- many. What church are you?'

'Anglican, but I don't believe in God.' 'Not at all?' Stanley asked, fingering his guitar-neck.

I paused. 'Well, no.'

They looked at each other wide-eyed. Stanley came at me, his ratty face solemn.

'But Humphry, look around you. The sun rises every day. The Earth gives us food. We have been given souls. Now who keeps this going?'

I gave my unremarkable opinions on the second law of thermodynamics, the origin of life and the descent of man.

Stanley laughed knowingly. 'It's funny,' he said, 'I've heard all this before, from an educated man like you. But education is not understanding. Don't you see, you're not an animal, you're not a monkey. Because, my friend,' he whispered, 'you have a soul. Yes, an immortal soul! You are made in God's image, to give Him worship and glory!'

'Well, perhaps. But then so does a monkey or a dog. Their souls are just simpler.'

`No, the animals are not in God's image. They are God's gift to us, to serve us and give examples.'

'What do you mean?'

'A dog eats what it pukes up, OK? Now this is an example. Would you do that? No! Because you're not an animal, you're a man. And the ant is always at work, running around, to tell us we must work too. That's another example. And the greatest example is other men. You meet Andrew and me, now we speak the same, don't we? You see the same love in us, love of God, love of you; and this is an example to you. You will leave here, go back to England, knowing what it's like to live in the truth. And so you will understand.'

Silence. They smiled broadly. I smiled back. Andrew went off to join the other busy ants. Stanley picked up his guitar, and we went to sit down next door. Eyes shut, he started strumming an anodyne tune. 'Humphry, you must know that every- thing that happens is God's will. I'll give you an example. Three weeks ago I killed my best friend.'

'WHAT?' 'I shot him dead.' Strum, strum. He smiled wistfully. 'One moment here, the next moment gone. That was God's will, my friend.'

I was lost for words. He went on to explain how God had miraculously put a bullet in his empty pistol, and ordained that he should plug his friend between the eyes.

Andrew and Mr Mathis came to ask Stanley to play out in the lavatory. The pipe was now going round. Stanley sat down on Giant's knees, took a long drag, dribbled into the bowl, and asked for requests. Everyone looked at me.

`Um, how about "Summertime"?' He looked unsure, so I hummed the opening lines.

'Oh yes, "Summertime".' He played a strange intro, then launched into song: 'We're all going on a summer holiday, /No more workin' for a week or two . . Everyone applauded at the end.

'Another one, please', said Stanley. 'Something religious?' He looked soulful.

I chose 'One Love' by Bob Marley. Half of the gang sang along, going into harmony for the refrain, 'Let's praise the Lord and we will feel alright'. The pipe and the sherry went round. The rain drummed on the roof. It was all strangely moving.

'Having a good time?' Andrew asked.

'Great, thanks.'

`So you like this place? You like our country?'

The dreaded 'South Africa' question, which I'd fielded so many times before, with studied vagueness. But now I was full of fellowship, not to mention communion- sherry. I spoke with feeling about the hatred that had divided, the goodwill in the hearts of so many, the love and under- standing that would unite all races.

They did not like this at all. Giant started the onslaught. Peering round Stan- ley, he said, `So you want me to give it all away? You want me to be the slave of fucking Nelson Mandela?'

Suddenly they were all at it, some shrugging and frowning as they patiently explained, some yelling into my face that the blacks were savages who would kill them and me if they had the chance. I had slowly backed out into the yard, muttering feebly.

'No, man,' Boris shouted, 'nobody stole nuttin' from the fucking kaffirs. Before the white men came, they was monkeys.' To much laughter and applause, he danced around 'like a savage', whooping and rolling his eyes.

'Blood River, now, it wasn't always called Blood River.' (Murmurs of agree- ment.) 'It was called — who cares — Gubblungbongo River, maybe. But when the Boers sit there, and the kaffirs come over the hill' — he did his 'savage' act again — 'and the Boers just go "bang" ' — he mimed a rifleman — 'and the kaffirs . . . and the Boers. . .' (he mimed the two parts over and over again, to more laugh- ter) 'and that's why it's called Blood River, man.'

The battle of Blood River is commemo- rated every 16 December, as the moment when the Afrikaners became a chosen people in the eye of God. The ANC and others keep it as a day of mourning.

'You see, Humphry,' said Stanley, 'we don't hate black people. But they are savages. Uncivilised. Maybe you thought we were black . . . ' He looked round to the audience.

'No, I know you are Coloured.'

'Yes, right, and that means we are civilised, we have something from the white man. We are nice, we welcome you, we like talking to you; you like talking to us. That is our pleasure. But the black man' — he looked at me sorrowfully — 'he has another pleasure, savage pleasure, to kill you. It's different blood, you see.'

'But if you're Coloured you also have that blood in you.'

There was a hostile silence. Andrew broke it with a laugh. `Ja, but even your great-great-great-back-and-back grand mother was a kaffir once. Adam and Eve were kaffirs, you told us in the kitchen.' Derisive laughter.

'He's right. Andrew,' said Stanley sym- pathetically. 'Everyone was once a savage.

But once you're civilised, you're civilised.'

He began preaching to the multitude. 'The Devil ruled the world once. He ruled in every soul in the world. But God came down to save us, and His power is greater than the Devil's. Once He enters your soul' — he paused dramatically — 'the Devil is cast out! Forever!

'But the Devil is in the black men's soul. They worship spirits; they are the witches, you see? If a black man wants something, he doesn't talk to you or wave a gun, like us; he pulls out little bones and does black magic.' Everyone laughed and nodded.

'And why are they so full of hate? That's not politics, it's the Devil inside them. And we fight the Devil; I'll give you an exam- ple, Humphry. Just last week, the fucking ANC was going to hold a meeting near here. But we got to the hall first! We prayed and sang hymns. And when they came, they forgot their fucking politics!'

He spat the word out viciously. 'They heard the word of God, and they sang with us!' He stared at me in triumph as the crowd laughed and applauded. `So I say to you, Humphry, I pray to you that you leave from here with some more under- standing.'

Ruby called me, Andrew and Stanley in for lunch — bread, margarine and mince.

Cyril came by with his enormous drunken father. Cyril wrestled respectfully with the foulmouthed old man every time he tried to get his hands on a drink. When he found out I was English, he gave me a long, grumbling monologue about his time in the war, the ignorance of the younger genera- tion, and so on. It was boring, of course, but pleasantly familiar. Cyril got up to go.

'Stay another day, Humphry', wheedled Andrew. 'Please; what are we going to do without you?'

I politely declined. I exchanged addres- ses with several people, and said a warm goodbye to Ruby. She kissed me and said, 'Now you will phone sometime? And not from Durban — from London, OK?'

'May God be with you', Stanley said with meaning.

I shook hands all round, and got in the car with five other people. We drove into the centre of town; Cyril's father sat on me, grumbling and belching. There were no coaches, so we set off towards a good hitching-spot; but as I knew he would, Cyril drove all the way to Grahamstown, about sixty miles. Thank God, my only contact in the town, whom I'd never met, was in. We said goodbye at her door. Cyril, smiling distantly in his blue hat, drove away through the downpour.

'Come in,' said Janet. 'Would you like some whisky?'

Previous page

Previous page