Books

Dickie: Lust for Glory

Max Hastings

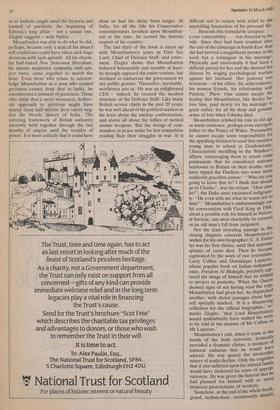

Mountbatten: The Official Biography Philip Ziegler (Collins £15) professional conservatism and an ex- aggerated sense of social propriety have been historic hallmarks of officers of the Royal Navy. How odd it is, there- fore, that the two most famous British naval officers of the 20th century have been almost' unqualified bounders. Both Beatty and Mountbatten were character- ised by shameless vanity and ambition. They flaunted their wealth in a fashion that Would have embarrassed a newly ennobled brewer. They embarrassed their peers with the complexity of their family lives. Above all, perhaps, on their bridges at war each proved fatally reckless. Unlike Nelson — in other respects a kindred spirit — their national celebrity as seadogs was not Matched by their competence as naval commanders.

When Mountbatten's official biography Was commissioned, given the nature of the Man, hagiography seemed inevitable. The author's publishers have done him no service with their fulsome jacket blurb, Which concludes that 'Philip Ziegler has Produced a masterpiece', a hype the less excusable since Ziegler was their editorial director. Yet once inside this book, its quality becomes indisputable. It is an outstanding tribute both to the author and to the Mountbatten family that the finished Work is as full, as balanced, as frank as any reasonable reader or historian could de- mand. Philip Ziegler concludes with a personal note about his subject quite un- characteristic in an official biography: 'His vanity, though child-like, was monstrous, as ambition unbridled . . . He sought to rewrite history with cavalier indifference to the facts to magnify his own achievements. There was a time when I became so enraged by what I began to feel was his determination to hoodwink me that I found it necessary to place on my desk a notice saying: REMEMBER, IN SPITE OF EVERYTHING, HE WAS A GREAT MAN.' And so, of course, he Was. The central interest of Mountbatten's career lies in determining whether his greatness was earned, or thrust upon him. Ziegler provides all the evidence to make this Judgment possible. Mountbatten was propelled through his life. by a boundless energy and capacity for action, matched by an almost complete incapacity for reflection. Legend suggests that his ambition was given early impulse bY. the great injustice done to his father, Prince Louis of Battenburg, who was

deposed from his position as First Sea Lord in 1914 because of his German lineage. In reality, there seems to be some grounds for questioning whether Prince Louis was quite the great naval strategist his admirers suggest. There is no doubt that he was badly treated, and that his younger son possessed a passionate ambition to restore the family name to greatness. But one may assume that the boy's ambition would have taken fire with or without that family injustice. The young Mountbatten drove through

the lower ranks of the Royal Navy like some advanced motor torpedo boat under uncertain control. After wartime service as a midshipman on Beatty's Lion, he became a lieutenant with a reputation for excep- tional technical efficiency and charm in handling men. Close companionship with the Prince of Wales and marriage to Edwina Ashley with her vast fortune earned suspicion and resentment from some colleagues and superiors for his playboy existence off duty. On the polo field, as a pilot, as a seaman, success did not come to him from natural ability. He compensated by absolute dedication, an infinite capacity for taking pains. Critics of his night life could scarcely fault an officer who never failed on duty to give of his utmost, who passed out top of his special- ised signals course and displayed a passion- ate interest in new technology. His person- al courage was matched only by his lust for glory. 'What an opportunity for anyone to earn an Albert Medal', he wrote in frustra- tion when a young seaman fell overboard from Warspite and was drowned while he himself was unluckily below. 'Wish I'd been on deck.'

Mountbatten adored being rich, and indulged himself prodigiously in servants, cars, boats, homes. His bedroom was remodelled to resemble an officer's cabin, with a porthole which revealed a diorama of Valetta harbour with model ships which could signal to each other. When this was completed, he held a press viewing. His weekend guests in Hampshire were pro- vided each evening with a docket which they were required to complete and return to the staff, declaring what they wished to do the following morning and afternoon. A second docket enabled them to indent for available cars, ponies and suchlike. No extravagance was too vulgar, no presump- tion excessive that enabled Mountbatten to improve a polo team, win a race, secure a decoration or gain an appointment.

'He possesses a naive simplicity com- bined with a compelling manner and dyna- mic energy', declared his final report in 1938, on completing a posting at the Admiralty. 'His interests incline mainly towards the material world and he is, therefore, inclined to be surprised at the unexpected; he has been so successful in that sphere that he does not contemplate failure. His social assets are invaluable in any rank to any Service. His natural thoroughness is extended to sport. Desir- able as it is to avoid superlatives, he has nearly all the qualities and qualifications for the highest Commands.'

Mountbatten weathered the Abdication

crisis without being compelled to make the dangerous gesture of serving as best man at the Windsor wedding, although he was loyal enough to offer. His social and political connections were unmatched, fos- tered by lavish hospitality in London and Hampshire. Admirals not infrequently found themselves being wined and dined by young Captain Mountbatten in a fashion some would have been less than human not to find irksome. Throughout his career, his severest critics and most dangerous enemies were almost all drawn from the upper reaches of his own service. Nor was their hostility entirely founded on jealousy. Noel Coward's film In Which We Serve made Mountbatten and his war- time destroyer Kelly famous. Yet his re- cord in command was at best exceedingly unlucky. When he drove his ship gratuit- ously fast in heavy seas, she was struck by a wave which heeled her 50 degrees to star- board, inflicted severe damage and almost caused her to founder. Repairs were scarce- ly completed before she hit a mine at the mouth of the Tyne. After 11 weeks in dry dock, she emerged to be badly damaged in a collision with another destroyer. In the Norwegian campaign, she was torpedoed and almost sunk after rashly using her signal lamp at night in hostile waters. When Churchill sought to get Mountbatten the DSO for his achievement in getting his crippled ship home, the Navy would have none of it. The C-in-C Home Fleet re- marked acidly that 'owing to a series of misfortunes. . . Kelly had only been to sea 57 days during the war, and that any other captain would have done the same in bringing the ship home.'

In the Mediterranean, Mountbatten in- curred considerable criticism from Admiral Cunningham for his handling of his ships before Kelly was at last sunk by dive- bombers. 'The trouble with your flotilla, boy', ABC told one of Mountbatten's officers afterwards, is that it was thor- oughly badly led.' Ziegler declares this a harsh judgment, but himself agrees that 'Mountbatten was not a good flotilla lead- er, or wartime commander of destroyers. It is perhaps not too fanciful to equate his performance on the bridge with his prow- ess behind the wheel of a car. He was a fast and dangerous driver.'

The author is equally direct about his subject's sexuality. Mountbatten himself said, 'Edwina and I spent all our married lives getting into other people's beds.' Ziegler comments: 'In this he did himself less than justice. He conducted at least two protracted love-affairs outside his mar- riage, to the apparent satisfaction of both parties, but he was never promiscuous. Though he liked to imagine himself a sexual athlete, he seems to have had in fact only slight enthusiasm for the sport . . . If asked to choose between seduction by the most desirable of houris and a conversation about service matters with a person of influence, he would unfailingly have chosen the latter.'

Edwina, with her obsessive restlessness and neophilia, never provided Mountbat- ten with the private companionship for which he yearned, says the author, how- ever admirable a public prop as Vicereine of India. Mountbatten tolerated her affairs with sympathy and understanding. As for the allegations of his own homosexuality, 'never would he have sacrificed his career for lust. To suggest that such a man was actively homosexual seems to be flying not merely in the face of the evidence but also of everything we understand about his character.' Modern prejudice assumes that extreme masculine self-love must be ex- pressed in homosexuality. Yet it seems perfectly convincing to accept Ziegler's view that ambition was for Mountbatten a far more consuming passion than sex.

After the loss of Kelly in May 1941, Mountbatten toured America describing his experiences both in public to the American people, and in private to their leaders. He was a huge success. Americans always liked him, responding at once to the openness and showmanship which so often displeased his fellow-countrymen. Then on 25 October 1941, at the Prime Minister's urgent behest, he returned to London. Churchill, with his romantic enthusiasm for plausible heroes, had always appreciated Mountbatten. The glamour, the good looks, the enthusiasm for innovation, the physical courage, the royal connections, the serenely articulate self-confidence — all the qualities that irritated, even repelled his professional superiors — commended Lord Louis hugely to Churchill. In the course of the war, the Prime Minister proposed some extraordinary sudden promotions for his protégés. Many were quashed by service opposition. Yet he forced through the appointment of Mount- batten to become not only Chief of Com- bined Operations, but a member of the Chiefs of Staff Committee directing the war, at the age of 41. It was a remarkable posting which caused deep dismay in some quarters, above all, in the upper reaches of the Royal Navy. To this day, it is a matter of dispute among historians how far Mountbatten justified his elevation. In October 1941, Britain stood on the strategic defensive. This was not merely a temporary condition; for those directing the war, it was difficult to see how she could hope to embark upon a death struggle with Germany within the foresee- able future, if ever. The campaign in the Desert was a mere sideshow. Yet Churchill perceived — and this understanding lay close to the heart of his achievement as a war leader — that if the nation's spirit was to survive through the long, dreary, unre- warding years ahead, somehow the son- blance, the facade of offensive action must be maintained. His principal weapon in this became Bomber Command. The over- whelming balance of evidence suggests that Churchill never rationally believed that bombing could crush the Nazis. Yet he was compelled to preserve the pretence of this possibility, for it was the only credible means by which Britain could carry the war to Hitler.

Likewise, the raids of Combined Opera- tions against Occupied Europe were, and would remain, the merest pinpricks in their impact upon the enemy. Their critical role was in lifting the morale of the British people, and sustaining the faith of the outside world, above all, the Americans; Until 1944, the principal importance er Combined Operations was less in rehears- ing the techniques of amphibious warfare — though this was useful — than in providing a public legend. If this sounds a trivial reason to despatch men to do or die, it was net then. And in the field of public relations, Mountbatten possessed no equal in the services. He seemed to the outside world the perfect embodiment of the modern Royal Navy. It did not matter that his colleagues might quarrel with this judg- ment. It was not even important that Combined Ops was judged by much of wartime Whitehall to be a perpetual tennis party, 'all rackets and balls'. As a stag manager, Mountbatten admirably served Churchill's purpose through the two years that followed.

Ziegler makes a sound case that if Mountbatten must take partial responsibil- ity for the fiasco at Dieppe, this must also be shared by others, Montgomery among them. If many of the gadgets and plans and Operations that his command devised proved as absurd as Habakkuk — the iceberg aircraft carrier — he can also claim a share in the genesis of the Mulberry harbours and in the COSSAC planning for ID-Day in Normandy. Mountbatten work- ed enormously hard. He showed an im- agination that, if it was sometimes fantas- tic, was also a welcome antidote to the Pedestrianism of many other senior offic- ers. The enthusiasm and respect he gener- ated among the Americans should not be underestimated, for when they entered the struggle their first contact with some of Britain's service leaders inspired grave doubts in Washington whether they had Joined the right war with the right ally. The worst charges against Mountbatten were those that would dog him for the rest of his career: that he clogged his staff with a small army of toadies and favourites of questionable merit, and that he waged a relentless campaign for his own self- aggrandisement.

Yet among those who could forgive him these vices, he inspired respect, affection, loyalty. It is a reflection of the fact that Mountbatten had done so much better than many expected that when Churchill Proposed that he should go to South-East Asia as Supreme Commander in October 1943, the appointment seemed at least plausible. American enthusiasm for the Choice overrode the familiar British Senior Service objections. To understand both the appointment and Mountbatten's subsequent perform- ance, once again it is necessary to conceive the job principally in terms of show- manship and public relations. Churchill Was deeply conscious that the British forces in Burma believed themselves 'the forgot- ten army'. Starved of resources and air support, they had been driven back to the frontiers of India by Japanese troops who had shown themselves incomparably su- perior jungle fighters. Churchill knew that until the end of the campaign in Europe, the Eastern war must continue to take a decisively secondary place in Britain's strategic planning. No great forces could be released, no magic wand waved to change the balance of forces in Burma.

Yet to Churchill who loved and under- stood the value of grand gestures, the dispatch of the semi-regal Mountbatten was a superb gesture. It assisted a real, very important revival of self-respect among the British forces struggling in Burma. It enabled Mountbatten himself to fulfil a function at which he was supreme, touring a thousand jungle clearings and steaming airstrips and sweat-ridden bar- racks with his immaculate uniform and superb charm and assurance, talking to men about what the King had written to him last week, what the Prime Minister had said at dinner, how the President of the United States followed their doings With rapt admiration. If it was corn, it was a brand of corn that defies the cynicism of history, as those who witnessed it testify. Mountbatten contributed immensely to generating a new sense of purpose and direction among the British in Asia. By this alone, he justified his appointment. Not surprisingly, he encountered far more difficulties when he began to try to act as a real Supremo, directing the move- ment of forces. Mountbatten was never an executive commander, he was non- executive chairman of the board, a role he often found frustrating. Slim was doing the real fighting in Burma, and it was un- equivocally Slim to whom final victory belonged; the Royal Navy under Sir James Somerville resolutely refused to acknow- ledge Mountbatten's authority, and was even reluctant to allow him to visit its ships except as a guest. Only the RAF accepted a reasonable measure of subordination. Mountbatten chafed, complained to Lon- don without getting much satisfaction, created a huge staff with too little to do, and devised grandiose amphibious plans which resources were never ayailable to put into practice. All this was distressingly inevitable, yet unimportant in terms of Mountbatten's real role as a showman. Only in the upper reaches of the command structure did private exasperation with the Supreme Commander's posturings become widespread. At the end of the war, he earned considerable credit for the enlight- ened and effective fashion in which he resumed control of Britain's Far East possessions. Indeed, he displayed far more perception about the impending end of Empire, the need for an immediate new relationship with the leaders of formerly subject races, than either Britain's diplo- mats or the new Labour Government. However dubious had been Mountbatten's claims to high command when he was exalted in 1941, however gross his over- statement of his own achievement in South-East Asia, by the end of 1945 he had earned his place at the top of the service table.

His wartime dispatch at last completed, in the winter of 1946 Mountbatten was on the verge of being posted to a naval senior officer's technical course when the new sensation burst upon the world, that the Attlee government was to send him to India as Viceroy. Ziegler's book devotes 120 pages to the 18 months that followed, when Mountbatten presided over the astoundingly abrupt dismantlement of the Raj. This is reasonable in a work of this kind, for the Viceroyalty was undoubtedly Mountbatten's greatest achievement. For a reader, it lacks the originality of some other sections of the narrative, for the story has so often been told before: the shock in Tory circles in England when it became evident that Dickie, of all people, proposed cheerfully to preside over the abdication of imperial glory; Mountbat- ten's announcement of an abrupt timetable for the transfer of power; the hasty attempts at judicial separation of the races, followed by the slaughter of half a million or so Indians caught amid the hysteria and turmoil of partition, the beginning of Edwina's long affair — not a sexual one, Ziegler suggests — with Nehru.

Mountbatten was able to do what he did, perhaps, because only a man of his absurd self-confidence could have taken such huge decisions with such aplomb. All his charm, his half-baked New Statesman liberalism, his sincere modernist sympathy with sub- ject races, came together to match the hour. Even those who refuse to acknow- ledge Mountbatten as a man who earned greatness cannot deny that in India, he encountered a moment of greatness. Those who claim that a more measured, deliber- ate approach to partition might have spared those half-million lives surely neg- lect the bloody history of India. The tottering framework of British authority narrowly held together through the last months of empire until the transfer of power. It is most unlikely that it could have

done so had the delay been longer. In India, for all the bile his Conservative contemporaries lavished upon Mountbat- ten at the time, he earned the historic respect of his country.

The last third of the book is taken up with Mountbatten's years as First Sea Lord, Chief of Defence Staff, and retire- ment. Ziegler shows that Mountbatten behaved honourably and sensibly at Suez: he strongly opposed the entire venture, but declined to embarrass the government by any public gesture. Thereafter, inevitably, worthiness sets in. He was an enlightened CDS — indeed, he created the modern structure of the Defence Staff. Like many British service chiefs in the past 20 years, he was well ahead of his political masters in his fears about the nuclear confrontation, and above all about the follies of tactical atomic weapons. But the doings of com- manders in peace make far less compulsive reading than their struggles in war. It is

difficult not to return with relief to the unyielding fascination of his personal life: `. . . Beneath this formidable carapace . • a raw vulnerability . . . was fostered by his wife. Since they had been reunited after the end of the campaign in South-East Asia she had proved a magnificeni partner in his work but a termagant in his marriage. Physically and emotionally it had been a difficult period for her and she showed her distress by waging psychological warfare against her husband. Her jealousy was ferocious — of his office, his achievements, his woman friends, his relationship with Patricia.' Phew. One cannot escape the feeling that Mountbatten, like Beatty be- fore him, paid dearly for his marriage to great riches, for all his deep and genuine sense of loss when Edwina died.

Mountbatten relished his role in old age as uncle-confessor, perhaps even surrogate father to the Prince of Wales. Presumably he cannot escape some responsibility for the appalling decision to send that sensitive young man to school at Gordonstoun. Characteristic meddling in the Windsor's affairs, encouraging them to return some possessions that he considered national heirlooms to Britain on their deaths, may have tipped the Duchess into some more ruthlessly graceless course: "Who are you going to leave that to? I think that should go to Charles", was his refrain. "How dare he!", the Duke once exclaimed indignant- ly. "He even tells me what he wants left to him!".' Mountbatten's embarrassingly VP' ful conversation with Cecil King in 1968, about a possible role for himself as Nation- al Saviour, can most charitably be excused as an old man's fall from judgment. Not the least revealing passage in the closing chapters concerns Mountbatten s wishes for his own biographer: C. S. Fores- ter was his first choice, until that supreme spinner of yarns died. Then he became captivated by the work of two journalists, Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre, whose popular book on Indian independ- ence, Freedom At Midnight, precisely cap- tured the image of himself that he wished to project to posterity. When the Queen showed signs of not having read the copY Mountbatten had given her, he dispatched another, with choice passages about hir- self specially marked. 'It is a disquieting reflection for the official biographer, re- marks Ziegler, 'that Lord Mountbatten would undoubtedly have wished his .storY to be told in the manner of Mr Collins or Mr Lapierre.' Mountbatten's end, when it came at the hands of the Irish terrorists, ironicallY_ provided a dramatic climax, a moment ot national catharsis that he would have adored. He was spared the intolerable misery of senile decline. Only the tragedies that it also inflicted upon his adored famtlY would have darkened his sense of approp- riateness. He was given the funeral that he had planned for himself with so many insincere protestations of modesty. Somehow, at the end of the whole brash, grand, technicolour, occasionally absurd, sub-Dynasty farrago of a life, the old Showman commands laughter and affec- tion. If he had failed in his manic lifelong quest for fame and baubles, his story would seem pathetic. But he did not fail. He succeded triumphantly, and by his success Justified all. It is a tribute to Philip Ziegler that his tale leaves behind an infectious sense of warmth and pleasure. Any instinc- tive Mountbatten family reservations ab- out this biography should be forgotten amid the certainty that historians a genera- tion hence will acknowledge the judicious excellence of Ziegler's work, when so many other officially-inspired lives have long since been consigned to the dustbin.

Previous page

Previous page