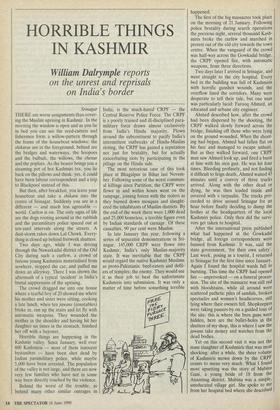

HORRIBLE THINGS IN KASHMIR

William Dalrymple reports

on the unrest and reprisals on India's border

Srinagar THERE are worse assignments than cover- ing the Muslim uprising in Kashmir. In the morning the window is open and as you lie in bed you can see the reed-cutters and fishermen form a willow-pattern through the frame of the houseboat windows: the shikaras are in the foreground, behind are the bridges and waterways, the hoopoes and the bulbuls, the willows, the chenar and the poplars. As the bearer brings you a steaming pot of hot Kashmiri tea, you lie back on the pillows and think: yes, it could have been labour correspondent and a trip to Blackpool instead of this.

But then, after breakfast, you leave your houseboat and take a shikara into the centre of Srinagar. Suddenly you are in a different — and much less agreeable world. Curfew is on. The only signs of life are the dogs rooting around in the rubbish and the paramilitary police spaced out at ten-yard intervals along the streets. A dust-storm rakes down Lal Chowk. Every- thing is closed up behind fretwork shutters.

Two days ago, while I was driving through the Nawarkadal district of the Old City during such a curfew, a crowd of furious young Kashmiris materialised from nowhere, stopped the car, and pulled me down an alleyway. There I was shown the aftermath of a typical 'incident' in India's brutal suppression of the uprising.

The crowd dragged me into one house where a tearful boy of 20 showed me where his mother and sister were sitting, cooking a late lunch, when ten jawans (constables) broke in, ran up the stairs and let fly with automatic weapons. They wounded the mother in the shoulder and having hit her daughter six times in the stomach, finished her off with a bayonet.

Horrible things are happening in the Kashmir valley. Since January, well over 600 Kashmiris — most of them innocent bystanders — have been shot dead by Indian paramilitary police, while maybe 5,000 have been arrested. The population of the valley is not large, and there are now very few families who have not in some way been directly touched by the violence.

Behind the worst of the trouble, as behind many other similar outrages in India, is the much-hated CRPF — the Central Reserve Police Force. The CRPF is a poorly trained and ill-disciplined para- military force drawn almost exclusively from India's Hindu majority. Flown around the subcontinent to pacify India's intermittent outbreaks of Hindu-Muslim rioting, the CRPF has gained a reputation not just for brutality, but for actually exacerbating riots by participating in the pillage on the Hindu side.

The most notorious case of this took place at Bhagalpur in Bihar last Novem- ber. Following some of the worst commun- al killings since Partition, the CRPF were flown in and within hours went on the rampage, joining forces with the rioters as they burned down mosques and slaught- ered the inhabitants of Muslim districts. By the end of the week there were 1,000 dead and 25,000 homeless, a terrible figure even by Indian standards of carnage. Of these casualties, 90 per cent were Muslim.

In late January this year, following a series of separatist demonstrations in Sri- nagar, 145,000 CRPF were flown into Kashmir, India's only Muslim-majority state. It was inevitable that the CRPF would regard the native Kashmiri Muslims as proto-Pakistanis: beef-eaters and defil- ers of temples; the enemy. They would see it as their job to beat the unfortunate Kashmiris into submission. It was only a matter of time before something terrible happened.

The first of the big massacres took place on the morning of 21 January. Following police brutality during search operations the previous night, several thousand Kash- miris broke the curfew and marched in protest out of the old city towards the town centre. When the vanguard of the crowd was half-way across the Gowkadal bridge, the CRPF opened fire, with automatic weapons, from three directions.

Two days later I arrived in Srinagar, and went straight to the city hospital. Every bed in the building was full of Kashmiris with horrific gunshot wounds, and the overflow lined the corridors. Many were desperate to tell their tale, but one man was particularly lucid: Farooq Ahmed, an educated and urbane city engineer.

Ahmed described how, after the crowd had been dispersed by the shooting, the CRPF walked slowly forward across the bridge, finishing off those who were lying on the ground wounded. When the shoot- ing had begun, Ahmed had fallen flat on his face and managed to escape unhurt. But as they walked forward, one CRPF man saw Ahmed look up, and fired a burst at him with his sten gun. He was hit four times. Bleeding profusely, and not finding it difficult to feign death, Ahmed waited 45 minutes until a convoy of three trucks arrived. Along with the other dead or dying, he was then loaded inside and covered with a tarpaulin. The trucks pro- ceeded to drive around Srinagar for an hour before finally deciding to dump the bodies at the headquarters of the local Kashmiri police. Only then did the survi- vors get taken to hospital. After the international press published what had happened at the Gowkadal bridge, all foreign correspondents were banned from Kashmir. It was, said the state government, 'for their own safety'. Last week, posing as a tourist, I returned to Srinagar for the first time since January. Again I found the hospital wards full to bursting. This time the CRPF had opened fire — unprovoked — on a funeral proces- sion. The site of the massacre was still red with bloodstains, while all around were scattered pathetic piles of sandals, broken spectacles and women's headscarves, still lying where their owners fell. Shopkeepers were taking passers-by on a guided tour of the site: this is where the bren guns were hidden, here are the bullet-holes in the shutters of my shop, this is where I saw the jawans take money and watches from the dead bodies.

Yet on this second visit it was not the mass slaughter of Kashmiris that was most shocking: after a while, the sheer volume of Kashmiris mown down by the CRPF ceases to mean very much. What I found most upsetting was the story of Mubina Gani, a young bride of 18 from the Anantnag district. Mubina was a simple, uneducated village girl. She spoke to me from her hospital bed where she described what had happened with a terrible, inno- cent straightforwardness. On 18 May, she said, she was coming back from her wed- ding at 11 o'clock at night, being escorted by her new family to their home. As Kashmiri tradition dictates, beside her in the bus, holding her hand, was her aunt, a woman of 40 and seven months pregnant.

Half a kilometre from their destination, the wedding party drew up before a road- block. As the driver pulled the bus to a halt, the paramilitary police at the check- point opened fire, killing the groom's brother. As the wedding party took refuge under the seats, the police boarded the bus through the windows. They attacked everyone — male or female — with rifle butts, then herded outside anyone who could still stand. At gunpoint they were made to line up in a row, with their hands up above their heads. The two ladies were then taken to a nearby field.

'We were dragged along and when we resisted they beat us again with their rifles,' said Mubina. 'They stole all our orna- ments, including my new wedding ring. Then they took off their clothes and ordered us to do the same. I wept bitterly and told them I had not yet seen my husband. They laughed, then between four and six persons raped first me, then my auntie.' With events in Eastern Europe dominat- ing the headlines over the last few months, the Kashmiri uprising, like the intifada, has received little space in the international press. Yet Kashmir, an independent princely state until 1947, should have as much right to decide its own future as, say, Lithuania. When Mrs Thatcher offers to mediate between India and Pakistan over the issue, she overlooks this essential principle. As Nehru said in a report to the All-India Congress Committee on 9 July 1951: 'Kashmir has been wrongly looked upon as a prize for India or Pakistan. People seem to forget that Kashmir is not a commodity to be bartered. It has an individual existence and its people must be the final arbiters of their future.'

India and Pakistan have already fought three inconclusive wars over Kashmir, and a fourth is now brewing. As both sides probably now possess nuclear weapons this must clearly be avoided at all costs. In the long term, only a plebiscite among Kash- miris on both sides of the border — as ordered by a United Nations resolution of 1948 — can hope to resolve the issue and bring peace to the region.

Britain is at least partly responsible for the current crisis. It was Britain that in 1846 originally hoisted a Hindu maharajah on the Muslim Kashmiris, and then, in 1947, we let Hari Singh, the Maharajah of the day, take his state into India without first consulting his people. If we have largely forgotten this, the Kashmiris have not.

Last week I watched as tens of thousands of Kashmiris gathered in the Id Gah Park for a memorial service commemorating the murdered religious leader, Mirwaiz Mulvi Farooq. As the crowds circled the Martyr's Graveyard, chanting 'Allah-u-Akbar!' waving nationalist banners and scattering baskets of rose petals on the graves, I was approached by two earnest-looking Kash- miri students holding a banner inscribed 'Democratic Nations: Where Are You?'

'What is your good country?' they asked. I told them.

'Britain is the mother of democracy,' said Afzal, the older of the two. 'Why is your country not standing up for our rights?'

I tried to explain that Britain did not have quite the same influence over India that it once did, but Afzal would have none of it.

'The British have always loved Kash- mir,' he said. 'You have guided our his- tory. Now all we ask for is a plebiscite. Please tell your countrymen. They have a duty to plead our cause.'

Previous page

Previous page