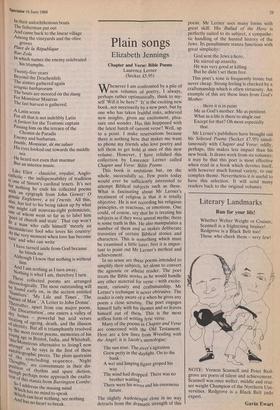

Sisson at seventy

David Wright

Collected Poems C. H. Sisson (Carcanet £14.95)

In the light of so magisterial a collection 'there is no disputing Robert Nye's large claim, quoted on the dustcover, for placing C. H. Sisson 'on the short shelf reserved for the finest twentieth-century poets, with Eliot and Rilke and MacDiarmid'. As an arrant Sassenach, Mr Sisson may have gagged a bit at being linked with the Caledonian Syzygy. But like MacDiarmid, and unlike that other very English charac- ter, Philip Larkin, Sisson is the least parochial of poets — witness his refashion- ings of Virgil, Ovid, Horace and Propertius (alas not included here), not to mention his full-scale translations of Catullus, Dante, du Bellay and Heine. And in youth he had his perceptions sharpened and range of experience enlarged by residence in Nazi Germany, pre-war France, and in the India of the Raj, where he served as an NCO during the war. Sisson now lives in the West Country of his farming forbears, not far from his native Bristol; but most of his life has been spent as a civil servant in Whitehall, where he was 'civil/To every- one, and servant to the devil'.

Until very recently, his name was un- known except to a few. He was a late starter. Not till he was nearly 40 did he seriously begin to write; and it is worth remarking that two-thirds of his poetry was written after his 50th birthday. It was the publication of In the Trojan Ditch ten years ago, enthusiastically reviewed by Donald Davie, that put him on the map. Until then, Sisson had found it extraordinarily difficult to get his poems accepted by editors of literary periodicals (astonishing- ly enough, publishers were more recep- tive). To this I can testify because the late Patrick Swift and I were the first to print him in 1960 in the quarterly magazine X which, for the brief period that it survived, remained practically his sole outlet till Michael Schmidt came to the rescue with Poetry Nation in 1973. But it's not hard to understand why Sisson was so neglected to begin with. For one thing, he was an absentee from what's too truly called 'the poetry scene'. For another, his poems — apart from never quite jibing with what- ever happened to be the current trend — are characterised by intellectual ferocity- His vision of things as they are is clear of all sentimental compromise:

Where the hare with its slight thoughts Passes and the badger leaves his bones My eyes fill with them and the fields, But this boy with the gun has the right idea: It is by killing we join in their fun.

bleakness e o Nature vision u re dominant in his brilliant novel, Christopher Honzm, first published in 1965, thoug,h e a Lover)is also That obsidian written ten years earlier. Here, with dead" pan Swiftian irony, Sisson traces the prog' ress, or regress, of a lower-middle-class homme moyen sensuel impoverished by every material and spiritual loss that coo' temporary civilisation can inflict, from squalid death to loveless birth (the story i5 told backwards). It so frightened the liter" ary agent to whom it was confided that he with such a book. to have anything to do it Despite this wintry vision of things as they are, as with all authentic poets it is for,. delight that one reads Sisson. He is one 01 the few real virtuosos of that most boobY` trapped of verse forms, so-called free verse; and his is a mastery of speech:1 rhythms and imagery learned from Poun and Eliot and T. E. Hulme. Witness the stanzas from his poem about the ultra; royalist Charles Maurras, whose intrinsic but unapt patriotism he understood 31161 had the courage to defend:

The light fell

Across the sand dunes and the wide Etang.

In their autochthonous boats The fisherman put out And came back to the linear village Among the vineyards and the olive groves

Place de la Republique Rue-Zola

In which names the enemy celebrated his triumphs.

Twenty-five years

Beyond the Drachenfels The armies gathered again

irruptio barbarorum

The boats are moored on the etang

For Monsieur Maurras The last harvest is gathered.

A Latin scorn

For all that is not indelibly Latin A fortiori for the Teutonic captain Passing him on the terrace of the Chemin de Paradis

Enemy and barbarian.

Inutile, Monsieur, de me saluer

His eyes looked out towards the middle

sea He heard not even that murmur But an interior music.

Like Eliot — classicist, royalist, Anglo- catholic — the indispensability of tradition is one of Sisson's cardinal tenets. It's not for nothing he ends his collected poems with an epigraph from John Gower: 0 gentile Engleterre, a toi j'escrits. All this, alas, has led to his being taken up by what °It° might call nouveau-right polemicists, one of whom went so far as to label him fit of church and state'. That cap won't t a man who calls himself 'merely an inconsiderate fool who loves his country/ At the very moment when love has become vain' and who can write

I have turned aside from God because he blinds me Although I know that nothing is without him

And I am nothing as I turn away; Nothing is what I am, therefore I turn. These collected poems are arranged chronologically. The most outstanding will be found early on, in the section entitled

Numbers':

_ 'My Life and Times', 'The Nature of Man', 'A Letter to John Donne'. thereafter, apart from one major poem, Discarnation', one enters a valley of dry bones — powerful but arid verses treating

of .a of ageing, death, and the illusion

bf identity. But all is triumphantly resolved Y the most recent poems, memories of his ?johlt. ng age in Bristol, India, and Whitehall,

Monstrous alternative to living/I now

attisi a..emPt. as he says in the first of these ourtobiographic pieces. The plain quatrains Thoughts the concluding sequence, 'Night are consummate in their dis- position of rhythm and spare diction, ti„ ugh perhaps none approach the exalta- 'Jo of this stanza from Buffington Combe: S I addresss the musing mind Which has no mind to speak WhiAnd ch can hear nothing, see nothing has no heart to break.

Previous page

Previous page