ARTS

Exhibitions

Mysterious dimensions

Giles Auty

A Selection of Important Sculpture (Marlborough Fine Art, till 31 August) Sculpture Show (Nigel Greenwood, till 30 July) While quite a number of painters have made excellent sculptors, how often has the reverse been true? Michelangelo, we know, regarded himself as a sculptor first, and quite a number of others, from his time to ours — Rodin, Giacometti, Moore and Hepworth, for instance — have also drawn beautifully, if in an essentially sculptural fashion. 19th- and 20th-century painters who made outstanding sculpture did so largely as an extension of their primary interest in the figure: Degas, Renoir, Matisse and Picasso.

Picasso's sculpture, like his ceramic de- coration, often has a wonderful gaiety, as though the adding of a third dimension relieved his tendency to darker broodings. The three three-dimensional pieces in the current Tate Gallery show of late works help lighten the overall tone of disquiet and remind us, instead, of their author's wit and sculptural inventiveness. A host of other small pieces, often assembled from bric-à-brac, have a similar leavening effect on nearby paintings at the Musee Picasso in Paris. Even some of the tiniest sculptural pieces made by Picasso exude an air of supreme self-confidence and good humour. In recent sculpture, such bouncy humanity has become increasingly rare. I do not find it, for example, in the work of Tony Cragg, Britain's representative at the current Venice Biennale, whose visual jokes seem too ponderous and studied. Much recent sculpture shares the familiar artistic failing of self-consciousness.

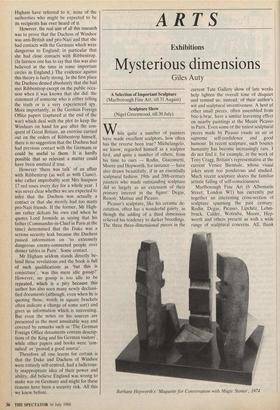

Marlborough Fine Art (6 Albemarle Street, London W1) haS currently put together an interesting cross-section of sculpture spanning the past century: Rodin, Degas, Picasso, Lipchitz, Lehm- bruck, Calder, Wotruba, Moore, Hep- worth and others present us with a wide range of sculptural concerns. All, thank Barbara Hepworth's `Maquette for Conversation with Magic Stones', 1974 goodness, work in traditional materials: bronze, stone and wood. Often, more evanescent sculptors from recent times have chosen to work in more destructible media. Such self-effacement is not without reason and may well spare bored owners and curators some tricky decisions in the years to come. Twenty years ago I recall a young architect trying to convert me to the joys of disposable housing. Luckily such ideas, which formed part of the radical orthodoxy of the moment, proved even shorter-lived than the throwaway buildings they sought to promote. One also wonders what has happened to the 'soft' sculptors of yesteryear? The hard-headedness of the more successful among them seems to have spread to their choice of materials, yet some ticklish decisions were left in their wake. One cannot but imagine that ex- hibits such as the lengths of dusty carpet underfelt which hung down, not so many years ago, from the walls of the Tate Gallery, present something of a problem for the museum conservation department. To beat it, shampoo it or try, as far as Possible, to forget about it? A prominent restorer spoke recently about the sad state of many recently-made paintings in public collections. This occurs because few present-day artists can be bothered to understand even the rudiments of paint chemistry or the necessity for proper sup- ports. Many sculptors seem no less arbit- rary in their choice of materials.

At Nigel Greenwood (4 New Burlington Street, London W1) three well- established, middle-generation sculptors work in an arbitrary-seeming variety of Media. Keith Milow's rusty-looking, geometric reliefs are made of lead-covered wood apparently. Why this particular choice of medium? Can lead rust? Yet the mystery of much modern sculpture extends way beyond mere choice of materials. Frequently its rationale seems as remote and unapproachable as inter-galactic space. Nor is it often redeemed by any- thing recognisable as beauty. Stephen Cox, recent recipient of an assisted passage to India, exhibits familiar fractured tondi and some disappointing drawings. He does not invoke the classical past so much as present disintegration. Joel Fisher displays what seem to be casts made from limbs, and minute minimal drawings. Richard Deacon, winner of last year's Turner Prize, will be represented shortly by 'Like a Snail . . . (A)' on the lawn of the Tate Gallery. This huge work, made from metal and hardboard, was conceived for an urban site in Munster, West Germany. Sites chosen for sculptural works are of vital importance; that outside the Tate Gallery clearly confers prestige. By con- trast, a good deal of modern-looking sculp- ture — some of it by cut-price pasticheurs — appears in such down-market settings as shopping precincts, up and down the coun- try. A singularly atrocious piece, known locally as 'The Flying Kipper' adorns just

such an environment, not far from where I live. My researches show its creator to be an American, resident in Spain. No one I have questioned from the art world has ever heard of him but other, more impor- tant, enigmas relating to commissions abound. A few years ago a friend of mine tried, with scant success, to discover the identity, artistic background and country of origin of 'Alexander' whose ultra costly- looking works may be seen at the South Bank (near the Shell Centre), Nottingham Hospital and Rutland Water. There is more to the business of modern sculpture than meets the eye.

Previous page

Previous page