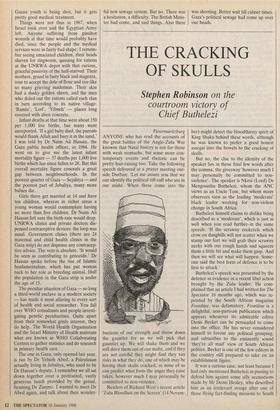

GAZA'S POLITICAL SEWAGE

Gerda Cohen finds out what

difference David Mellor's outburst makes for Palestinian refugees

Gaza YOU would think they'd be grateful, the doctors and nurses who have been trying hard to improve conditions in Gaza; you would think they'd be grateful for such a fortnight, impassioned visitor. But no, I regret to say the doctors and nurses were not best pleased. Dr Tulchinski, the Co- ordinator of Medical Services, was even heard to say, in the privacy of his office: 'That man is an ass-hole.' Well, Dr Tul- chinski did not have the advantage of going to Swanage grammar school, so he may be pardoned the vulgarity. Whereas the Junior Minister, applying the high stan- dards of Putney, was naturally taken aback — horrified even — by pools of Gaza sewage. He could not realise, in the course of half an hour, the complex political nuances of Gaza sewage.

For a start, it depends on which bit of sewage: refugee or non-refugee. UNRWA, the United Nations agency set up in 1948 to deal with the emergency needs of Palestinian refugees, has responsi- bility for sanitation in the camps. In the Gaza Strip, about two-thirds of the popula- tion live in camps which have become, over the course of 40 years, shambling over- crowded districts — one can't call them towns — without the essential infrastruc- ture needed by so many people. Jebaliya, for example, has the population of Croydon and the refuse collection suitable for a small Egyptian village. Anything which means permanency — roads, sewage pipes — has been rigorously avoided. UNRWA is now a very large organisation devoted to perpetuating the idea of the Palestinian Refugee, and sewage pipes simply do not help this idea. Only now, after 40 years, are sewage systems being installed in the camps in Jordan, in some of the biggest at least.

In the Gaza Strip, at long last, the problem of 'permanency' has been over- come by help from a neutral agency, the United Nations Development Program, which has funded and supervised the con- struction of major sewerage systems. The mains are being laid in Gaza town, and the work should have finished, but for the riots which broke out in December and continue today, more bitterly than ever.

'If we all lived in palaces, with two bathrooms, we should still want to go home, to Palestine,' I was told by a thin, earnest gynaecologist in Shifa General Hospital. They do not stop yearning for Zion, even after 40 years in the wilderness. I had first met that particular doctor in 1985, when going round the maternity unit. It was a dreadful, stinking, stuffy little place, where patients sometimes had to share a bed. The hospital director, Dr Ghaleb Zimmo, constantly beaming with his big yellow teeth, informed me that maternity cases stayed for 12 hours. Then he changed his mind. Still beaming, in a rush of dull Western truth, he exclaimed: 'To be frank, our ladies come, after half an hour they deliver, after half an hour they go home!'

Then Dr Ghaleb Zimmo showed us the foundations of the new surgical suite, and the intensive care unit. By good luck, these new facilities were ready to take care of young men with dreadful gunshot wounds inflicted by Israeli soldiers quelling the Gazan uprising. So too, in the south of the Gaza Strip, a complete modernisation of the surgical theatre in Khan Yunis hospital had been completed in time to receive the badly hurt youngsters from recent riots. Twenty-five senior nurses, fresh from a nursing administration course given by Israeli medical staff in nearby Ashkelon, were on hand to succour the wounded. Gazan youth is being shot, but it gets pretty good medical treatment.

Things were not thus in 1967, when Israel took over and the Egyptian Army left. Anyone suffering from gunshot wounds at that time would probably have died, since the people and the medical services were in fairly bad shape. I remem- ber seeing emaciated children, their heads shaven for ringworm, queuing for rations at the UNRWA depot with that curious, graceful passivity of the half-starved. Their mothers, grand in fusty black and magenta, rose to accept the dole of flour and rice like so many grieving madonnas. Their skin had a dusky golden sheen, and the men who doled out the rations called each clan in turn according to its native village: `Ramla', `Lod', `Yibneh' — places long covered with alien concrete.

Infant deaths at that time were about 150 per 1,000 live births, but many went unreported. 'If a girl baby died, the parents would thank Allah and bury it in the sand,' I was told by Dr Naim Ali Hassan, the Gaza public health officer, in 1984. He went on to give me the latest infant mortality figure — 37 deaths per 1,000 live births which has since fallen to 28. But this overall mortality figure conceals a great gap between neighbourhoods. In the poorest quarter of Gaza — Sejahiya — and the poorest part of Jebaliya, many more babies die.

Girls there get married at 14 and have ten children, whereas in richer areas a young woman would contemplate having no more than five children. Dr Naim Ali Hassan felt sure the birth-rate would drop. UNRWA clinics and private doctors dis- pensed contraceptive devices: the loop was usual. Government clinics (there are 24 maternal and child health clinics in the Gaza strip) do not dispense any contracep- tive advice. The veto is absolute. 'It would be seen as contributing to genocide.' Dr Hassan spoke before the rise of Islamic fundamentalism, which has put woman back to her role as breeding animal. Half the population in the Gaza strip is under the age of 15.

The peculiar situation of Gaza — so long a third-world enclave in a modern society — has made it most alluring to every sort of health and social researcher. You fall over WHO consultants and people investi- gating genetic peculiarities. Quite apart from their somewhat grisly interest, they do help. The World Health Organisation and the Israel Ministry of Health maintain what are known as WHO Collaborating Centres to gather statistics and do research in primary health care.

The one in Gaza, only opened last year, is run by Dr Yehieh Abed, a Palestinian actually living in Jebaliya, who used to be Dr Hassan's deputy. I remember we all sat down together over a protracted, vastly generous lunch provided by the genial, beaming Dr Zimmo. I wanted to meet Dr Abed again, and talk about their wonder- ful new sewage system. But no. There was a hesitation, a difficulty. The British Minis- ter had come, and said things. Also there was shooting. Better wait till calmer times. Gaza's political sewage had come up over our heads.

Previous page

Previous page