A sombre anniversary

Bohdan Nahaylo

These are bleak days for freedom in Eastern Europe. The blaze of hope which burned so brilliantly in Poland is be- ing doused, In East Germany supporters of Solidarity have been rounded up. In Czechoslovakia, where the human rights activists of Charter 77 and VONS — the Committee for the Defence of the Unjustly Persecuted — have been almost completely suppressed, the ebullient weeks of the Prague Spring must by now seem to many like a dream that never really took place. This month, moreover, the focus should be broadened to include Poland's eastern neighbour Ukraine where ten years ago on 12 January the Soviet authorities launched the most extensive political and cultural purge of the post-Stalin period in order to destroy a Ukrainian national revival which, had it been allowed to continue, might eventually have faced the Soviet leaders with as grave a crisis as the 'renewals' in Poland and Czechoslovakia. Despite its scale and significance, this extirpative cam- paign has been virtually ignored by the Western press. A decade later, for all the official efforts to 'normalise' the situation in the USSR's most important non-Russian republic, Ukraine remains a major headache for the Soviet leadership.

The 'General Pogrom', as it was named by the editors of an unofficial journal, began as a crackdown on Ukrainian dissent but soon developed into a broad drive against patriotically minded individuals who could hardly be described as dissidents. Scores of Ukrainians were ar- rested, including some of the most talented and forthright younger representatives of the nation's creative intelligentsia. Most were given heavy sentences of up to 15 years, ostensibly for 'anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda'. Thousands of others were subjected to searches, questioning, harassment and intimidation. One of the victims, the poet Vasyl Stus, protested in a document smuggled out of a labour camp that the repressions of 1972-73 had transformed the entire young generation of the nationally minded intelligentsia into a `generation of political prisoners' and 'in- flicted irreparable damage to the Ukrainian nation and its culture'.

That this operation was something far more ambitious and sinister than a police action against 'dissidents' was also borne out by the extensive sackings, demotions and personnel changes which took place throughout 1972-73 in the party, govern- ment, media, universities and schools. In May 1972, Petro Shelest, the first secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine (CPU), was abruptly removed from his post. At the time most foreign observers, seemingly

oblivious to what was happening in his fief- dom, attributed his fall to hard-line opposi- tion to détente. When almost a year later, however, the official charges against him were made public, Shelest was denounced for encouraging 'local nationalism' and `national narrow mindedness'.

Shelest, far from being a nationalist, at- tempted to come to terms with Ukrainian national feeling and to maintain a modus vivendi with the nationally minded in- telligensia. Together with his supporters within the Soviet Ukrainian establishment, he not only tolerated but actually promoted a Soviet Ukrainian patriotism, actively sup- porting the development of the Ukrainian language and culture. Consequently, the revival in Ukrainian culture and public life which had begun during the relaxation in the official nationalities policy following Stalin's death gathered momentum during Shelest's nine-year tenure of office, although by this time the Soviet leadership had embarked on a policy of integration through increased Russification and cen- tralisation. By the end of the 1960s Moscow was clearly concerned about the resurgence of Ukrainian national assertiveness and the danger that in Ukraine the party's formula of 'socialist in content' and 'national in form' would be stood on its head. Hence, the decision to bring the republic into line by stamping our Shelestism.

Shelest's successor Vladimir Shcherbitsky wasted no time in setting a new tone by demonstratively addressing meetings of the CPU in Russian. There was a return to the ritual eulogising of things Russian which had been obligatory in the last years of the Stalin era, and Russification was stepped up. Characteristically, at the beginning of 1979 on the eve of the 325th anniversary of what is officially and euphemistically described as the 'reunification' of Ukraine with Russia, Scherbitsky, having listed in- numerable benefits — political, military, economic and cultural — Ukrainians had enjoyed as a result of their unity with Rus- sians, wrote that 'the Ukrainian peoPl.e chose the only correct path for their development. Their great fortune lies in the fact that traversing this path illuminated bY the genius of Lenin, they are proceeding under the wise leadership of the Communist Party'. Significantly, the very same poems by the Ukrainian national poet Taras Shev- ehenko, previously censored by Tsarist and Stalinist officials, were once again banned. The 'General Pogrom' in Ukraine was the latest episode in the centuries-old ques- tion of the political independence or autonomy of Ukraine vis-à-vis Russia. In the 19th century under Tsarist rule the Ukrainians were treated as a regional off- shoot of the Russian nation and even education and publishing in the Ukrainian language were banned. After an unsuc- cessful attempt to achieve political in- dependence lasting from 1917 to 1920, most of Ukraine came under Soviet rule. Although 'in the Soviet Union the existence of a distinct Ukrainian nation was recognis- ed, in practice the Soviet authorities con- tinued to treat Ukraine as a politically unreliable provincial appendage of Russia. During the Stalin era, the Ukrainian in- telligentsia was decimated, and as a result of the collectivisation campaign of 1932-33, some six million Ukrainian peasants starved to death in the largest artificial famine in history. Not surprisingly, there was little love for Soviet rule in Ukraine when World War H broke out: an armed Ukrainian na- tionalist resistance movement fought both German and Soviet troops, continuing its guerrilla campaign in Western Ukraine until the early 1950s.

Today, considering the situation, size and economic wealth of Ukraine, not to mention the strength of nationalist feeling among many Ukrainians, Moscow can ill afford to relax its grip on this republic. Fur- thermore, the Ukrainians hold a special position with regard to the Russians who constitute barely half of the Soviet popula- tion. The 43 million or so Ukrainians in the USSR constitute by far the largest non- Russian nation in the Soviet Union and as Slays, together with the Byelorussians, are the closest culturally and linguistically of all the Soviet national minorities to the Rus- sians. With the Ukrainians docile because of concessions or coercion and assimilation, it becomes considerably easier for the authorities to manage national relations in the heterogeneous Soviet state in a way that for all the internationalist rhetoric reflects Russian pre-eminence. If they are restive, as the Lithuanian samizdat journal Ausra recently pointed out, the smaller non- Russian nations are afforded a powerful bulwark against Russian encroachments. 'To struggle alone is senseless', wrote the Lithuanian dissenters, 'That is why we place our hopes on you, Ukraine. If you are with us, we will triumph'.

The 'General Pogrom' failed to eliminate Ukrainian resistance. The latter takes many forms ranging from demands made by Ukrainian intellectuals for more publica- tions in Ukrainian and contacts with foreigners, to clandestine religious and op- positional activity. Ukrainian dissent sur- faced again in November 1976 in the form of the Ukrainian Helsinki monitoring group which, during its four-year existence, issued extensive documentation about the viola- tions of human and national rights in Ukraine. During the last decade Ukrainian dissenters, best characterised as national democrats, have become generally more militant and have been unequivocal in demanding Ukrainian independence from Moscow and calling for `decolonisation' of the USSR. The authorities have relied on the carrot and stick approach, attempting to conciliate the creative intelligentsia with modest concessions while clubbing dissenters with a ruthlessness unknown in other parts of the Soviet Union. Conse- quently, many more Ukrainians have been imprisoned in recent years, including over 20 members of the Ukrainian Helsinki monitoring group. A large proportion of those sentenced for political or religious of- fences have been convicted on the basis of false criminal charges unrelated to their dissenting activities. Nevertheless, despite the degree of repression in Ukraine, there were numerous indications in recent mon- ths that the authorities have been uneasy about the possible repercussions of the Polish events in this troublesome republic. Significantly last September, a campaign on a scale unprecedented since the Stalin era was launched in Kiev to recruit informers.

If the Soviet Union's 'Ukrainian pro- blem' is more often than not relegated to a position of unjust obscurity by the Western media, its importance is readily recognised by human and. national rights activists in the USSR and Eastern Europe. Dr Yuri Orlov, the imprisoned Russian Helsinki monitor, for instance, points out that more than 40 per cent of all political prisoners in the Soviet Union are Ukrainians. More recently, the Polish activists Jacek Kuron and Adam Michnik have sought to impress upon their compatriots that Poland's neighbour is not Russia but Ukraine. `There can be no independent Poland without an independent Ukraine', Kuron told a public meeting at Warsaw University a year ago.

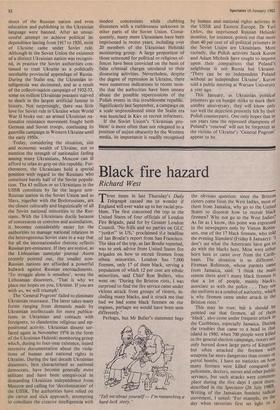

This January, as Ukrainian political prisoners go on hunger strike to mark their sombre anniversary, they will know only too well the dejection presently felt by their Polish counterparts. One only hopes that in ten years time the repressed champions of Poland's 'renewal' will not be forgotten as the victims of Ukraine's 'General Pogrom' appear to be.

Previous page

Previous page